WSJ’s Marketbeat reports of troubles Hungary may be headed into. The blog post reports:

Hungary this morning had its own T-bill auction, just like Italy. It did not go so well!

Hungary’s auction had a bid-to-cover ratio of just 1.0, and it had to pay a 6.79% yield to move the debt.

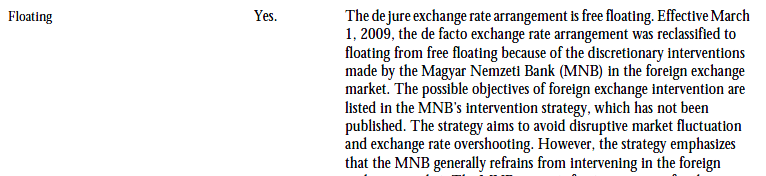

I decided to do some basic analysis of what is going on. The Annual Report On Exchange Arrangements And Exchange Restrictions 2010 reports that

and also that:

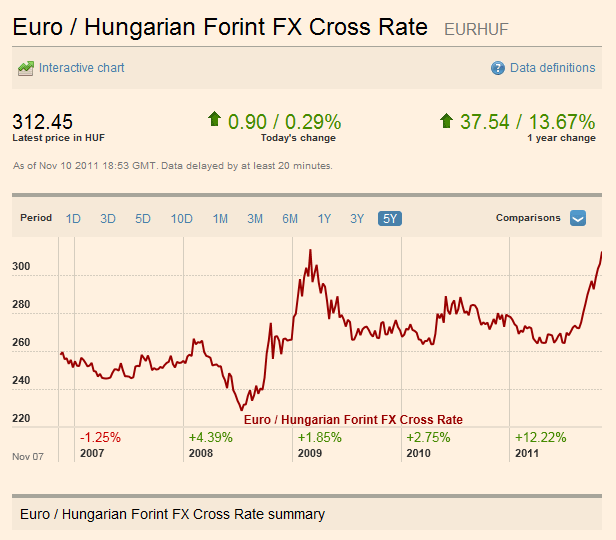

FT provides the chart of EURHUF:

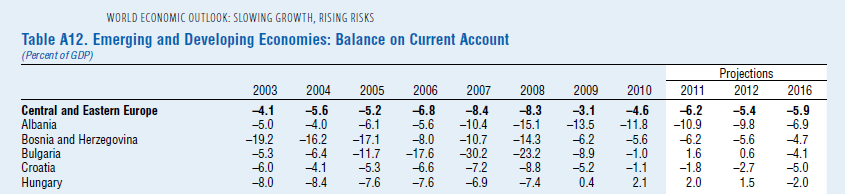

The depreciation got me even more curious. More screenshots from data sources below. The first one is Hungary’s current account balance as a percentage of GDP, courtesy IMF’s World Economic Outlook, Sep 2011.

(Click to enlarge)

So Hungary has been running a huge current account deficits since many years. A current account deficit means that a nation’s expenditure is higher than income and the difference has to be financed by net borrowing from abroad. During boom times, this may not be problematic but the accumulated debt has to be rolled by attracting foreigners by hook or crook. The route most chosen to prevent getting things out of control is be deflating demand. Only in a Mundell-Fleming fantasy world does the nation’s currency depreciate to bring the current balance of payments to zero and an equilibrium with respect to the external world.

Hungary is a small nation with GDP equivalent of €97b (in 2010, using an approximate average 2010 exchange rate of HUFEUR=0.0036. Note to self: This needs more correction). Due to deficits in the international current balance of payments, the nation has accumulated a debt equivalent of €113.59b (the negative of NIIP) according to the the release Hungary’s balance of payments: 2011 Q2 from Magyar Nemzeti Bank – Hungary’s central bank. With net foreign asset position worse than -100% of GDP, this puts Hungary’s economy in a terrible position. Recent data suggests an improvement in external trade but the international currency markets are not impressed.

According to this Wikipedia Map, Hungary is obliged to join the Eurozone, and has no opt-out option like UK. However, it has not satisfied the Maastricht criteria, and hence the Eurozone won’t let it in yet. Better not! As long as Hungary has its own currency, its government can make a draft at the central bank to finance a portion of its deficit and gives it a tool to protect itself in the short term. So Hungary is protected from being Greece as long as it is not in the Eurozone. But in the long run, Hungary’s growth will be constrained by its balance of payments.