The Eurosystem consists of the European Central Bank (ECB) and 17 National Central Banks (NCBs) of the member nations. The purpose of this post (and some that will follow) is to explain how the RTGS payment and settlement system called TARGET2 works in order to understand the flow of funds within the Euro Area. The purpose is also to show that money is endogenous in the Euro Area, that it cannot be otherwise and describe the Euro Area economic dynamics in the money endogeneity framework

First consider payments within a nation, i.e., domestic payments. In the Euro Area, it happens exactly in the way as in any nation. I had a post covering this – Payment Systems And Settlement. An example illustrates this:

Suppose a household A holding deposits in Bank A in Spain wishes to make a payment of €100 to an institution B banking at Bank B. The household A will give an instruction to her Bank A to transfer funds to Bank B. Assuming this goes through, the Spanish central bank Banco de Espana will debit Bank A’s account and credit Bank B’s account. Bank B will credit institution B’s account €100. If Bank A has insufficient funds at Banco de Espana, the latter will provide the former intraday credit free of charge.

So transactions such as the above give rise to payment flows in all directions. To understand how the Eurosystem handles this, it is useful to go into some rules.

The Guideline of European Central Bank of 30 December 2005 on a Trans-European Automated Real-time Gross settlement Express Transfer system (TARGET) (ECB/2005/16) 3(f) 1 says (link)

So within the day banks can go into overdraft at the home central bank by pledging collateral. In practice, banks have more collateral at the central bank to cover for daily fluctuations. Also, in the Euro Area, banks need to satisfy a reserve requirement of 2% which means that the amount of reserves deposited at the NCB should be at least 2% of the deposit liabilities. How do banks get the reserves when they lose reserves? During the day, the intraday credit itself provide the reserves. (Loans make deposits!). However toward the end of the day, banks may want to instead borrow from the rest of the financial system, instead of relying on central bank credit because the latter is free of interest only intraday and is charged an interest rate equal to that of the marginal lending facility overnight. Typically, this poses no problem because some banks may have excess reserves which they may want to lend out because keeping it deposited at the central bank will pay an interest equal to that of the deposit facility which is lower. So typically, banks would retire intraday credit toward the end of the day and borrow funds from the rest of the financial system.

An exception to the above arises during periods of market stress or crisis, when banks prefer to not lend the excess funds due to credit risks and are happy to keep funds deposited at the central bank despite earning lower interest.

As banks create more money by lending (more credit to be precise), the reserve requirement of the whole banking system would increase. How do banks in the Euro Area get more reserves?

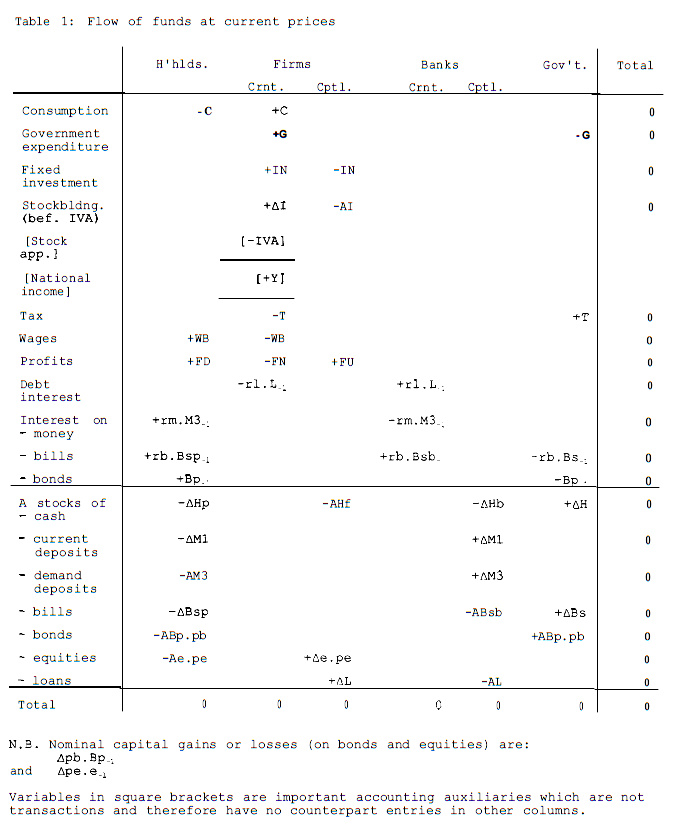

It is useful here to distinguish between two types of monetary systems – overdraft and asset-based. In the former, banks as a whole get all the reserves directly by borrowing from the central bank (provided they pledge good collateral) and in the latter, the central bank would create reserves required by the banking system by engaging in permanent open market operations or outright operations, typically purchasing government bonds. The Euro Area monetary system is best described by the former and Anglo-Saxon monetary systems such as one in the United States is best described by latter. Even in the latter, the Federal Reserve does provide direct credit to banks but these are retired quickly. The distinction can be made by looking at the balance sheet of the central bank.

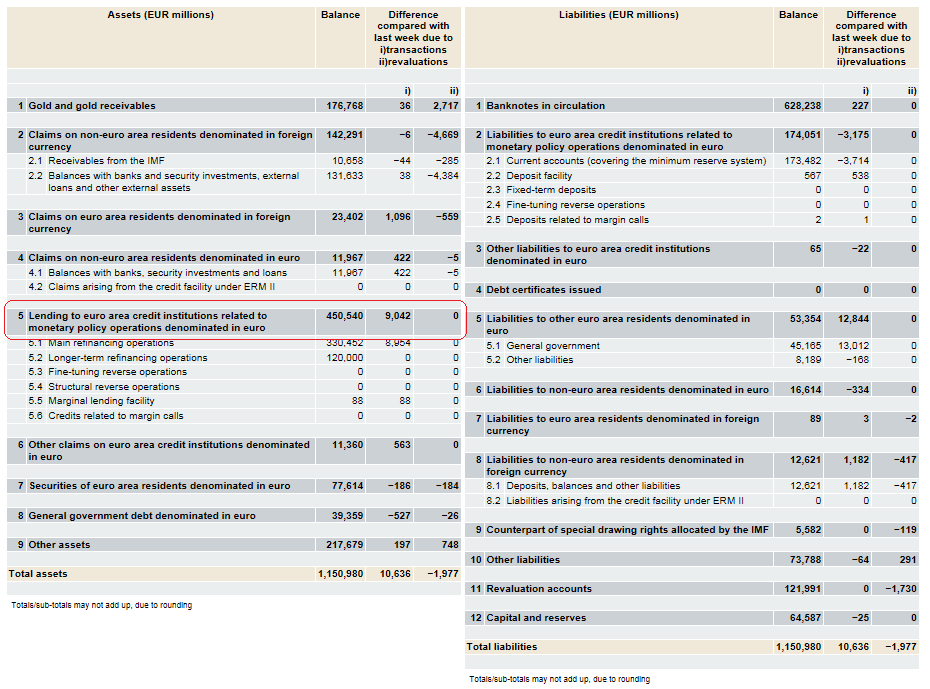

We are yet to see the Eurosystem being described as a whole, but for our purpose of clarifying how an overdraft system looks, it is sufficient to just take a glance at the consolidated balance sheet to verify. The Eurosystem balance sheet near the end of 2006 looked like this (link):

(click to enlarge)

The item rounded in red is €450, 540 million which is a big proportion of the total size of the balance sheet, and one doesn’t see this for the Federal Reserve (in normal circumstances).

Since the Eurosystem is an overdraft type, the funds obtained have to be provided by direct lending by the Eurosystem. This is done mainly via two types of operations – Main Refinancing Operations (MROs), and Long Term Refinancing Operations (LTROs), where the Eurosystem conducts an auction to lend the whole banking system. For the former, the auctions are held weekly and the lending is for one week. LTROs, it is typically conducted every month and the duration of refinancing is three months. As the names suggest, MROs are used mostly.

This will conclude my post. The posts following this will look at cross-border flows of funds and government accounts. They (either one post or two) will attempt to provide the reader an idea of how cross-border dynamics are important for the Euro Area.

Update: Corrected the discussion on frequency and duration of LTROs in the second last para.