S&P released another document yesterday in connection with the rating action of Eurozone governments yesterday which you can get via it’s Tweet:

click to view the tweet on Twitter

On the political agreements, the release says:

We also believe that the agreement is predicated on only a partial recognition of the source of the crisis: that the current financial turmoil stems primarily from fiscal profligacy at the periphery of the eurozone. In our view, however, the financial problems facing the eurozone are as much a consequence of rising external imbalances and divergences in competitiveness between the EMU’s core and the so-called “periphery”. As such, we believe that a reform process based on a pillar of fiscal austerity alone risks becoming self-defeating, as domestic demand falls in line with consumers’ rising concerns about job security and disposable incomes, eroding national tax revenues.

Two points.

First – yes, fiscal profligacy is not the only source of the crisis. It is typical to give the example of Spain and Ireland – and done by S&P itself – to justify this:

This to us is supported by the examples of Spain and Ireland, which ran an average fiscal deficit of 0.4% of GDP and a surplus of 1.6% of GDP, respectively, during the period 1999-2007 (versus a deficit of 2.3% of GDP in the case of Germany), while reducing significantly their public debt ratio during that period.

There is a risk in making such an argument and even progressives sometimes do so. The error is assuming that the public sector deficit is a proxy for the fiscal stance of the government! Macroeconomists using stock flow coherent macro modeling have shown that the budget balance is just an endogenous outcome and the more appropriate proxy for the fiscal stance is G/θ, where G is the government expenditure and θ is the average tax rate.

To me it seems both Spain and Ireland governments (and local governments) were actually lavish in their spending. The private sector was even more lavish in its expenditure and rising incomes led to higher tax revenues which improved the government’s budget balance before the crisis. The whole process was allowed to continue by market forces, domestic and foreign lenders who (not surprisingly) underpriced risk. Needless to say the lack of a central government overseeing demand management and the ignorance of Keynesian principles contributed to the haphazardness.

Second, most commentators – including the S&P – pay too much attention to price competitiveness. So typically one sees a graph of unit labour costs of individual nations in almost all analysis. One even does not need to take innovations in the export sector to explain the crisis.

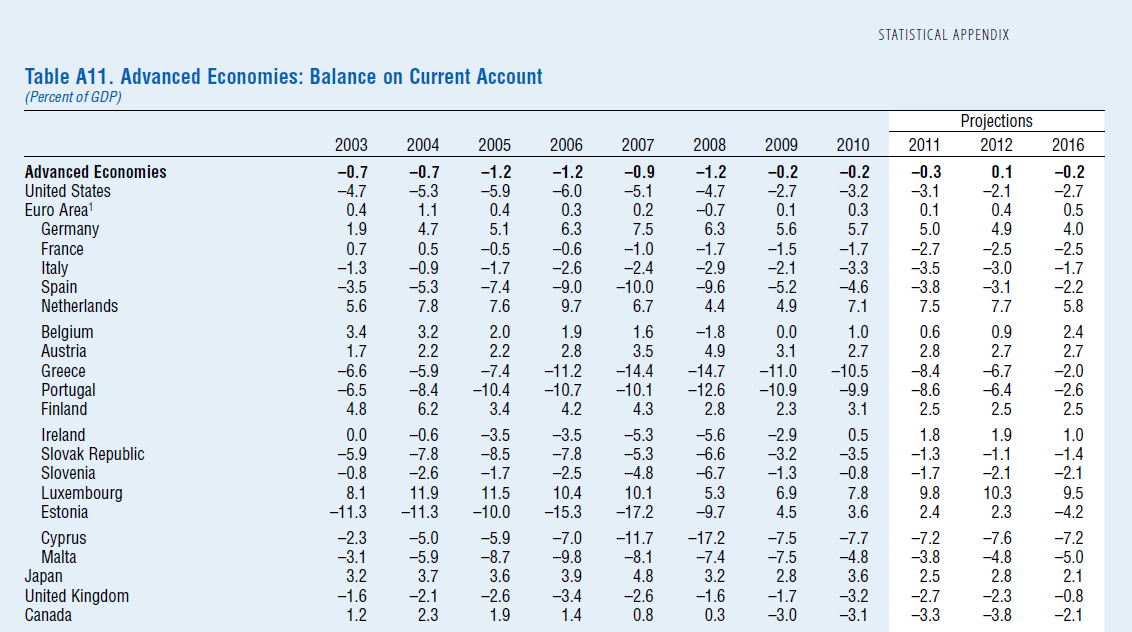

The EA17 nations had different levels of non-price competitiveness to begin with and faster growth of income/expenditure in the “periphery” as a result of the boom as compared to slower growth in the “core” nations led to exploding current account deficits. Here’s the data from the IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook published in September 2011 on the current account balances:

With different non-price competitiveness (or income elasticity of imports) (to begin with at the formation of the monetary union rather than innovations during the last ten years) combined with fast rising income/expenditure in the periphery, this led to a dramatic increase in net indebtedness of the periphery as a straightforward consequence. To emphasize the point, even if non-price competitiveness was similar between the core and the periphery, this would have resulted in rising net indebtedness.

It is surprising how international finance contributes to unsustainable processes from continuing as if they can continue forever!

Update

Paul Krugman has a new post on his NY Times Blog on the same comment from S&P from its FAQs but with a different viewpoint.