The Bank of England and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York reported the results of their survey of the volume of activity in the foreign exchange markets today. (here and here).

According to the Bank of England,

Average daily reported UK foreign exchange turnover1 was $1,972 billion in October 2011, 3% lower than in April 2011, and 17% higher than a year earlier.

and according to the Federal Reserve,

Average daily volume in total over-the-counter foreign exchange instruments (including spot, outright forward, foreign exchange swap, and option transactions) reached a record high of $977 billion in October 2011, compared with upwardly revised turnover figures of $856 billion in April 20111 and $809 billion in October 2010. The October 2011 total represented a 14.2 percent increase from the prior survey.

The Bank of International Settlements releases its own survey – the difference between its survey and that of central banks’ is the BIS collects data from banks’ sales desks while the central banks collect data directly from the dealers’ trading desks. (Minor point)

Why is this so high? (As compared to transactions in goods and services)

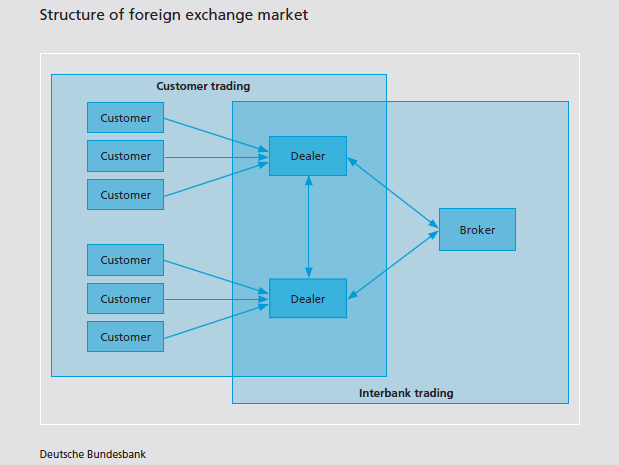

To understand this, we need to look at the mircostructure of the foreign exchange markets. Like all markets, the foreign exchange market has dealers and in this case its banks who make the markets.

Here’s a nice diagram from the Deutsche Bundesbank’s Monthly Report, January 2008

Two Way Quotes

Consider a EUR/USD quote such as 1.3063/1.3065.

buy/sell or bid/offer.

What does that mean?

If you as a customer (not the dealer) want to sell EUR, the dealer is bidding at $1.3063. That is, you enter into the transaction at this quote, you receive $1.3063 for every €1 you sell the dealer (dealer buys EUR). If you want to buy EUR, you pay $1.3065 for every €1 you purchase from the dealer (dealer sells EUR). The buy/sell is from the market maker’s perspective.

The quote (the spread actually) is always in the market maker’s favour because he/she runs the risk of a one-sided inventory.

Once the customer accepts the quote, the bank has “undesired” inventory. So it is looking to reduce this and needs another dealer who can be contacted through a broker or a broker’s trading system. Before the trade, the identity of the other side is confidential to the broker and is revealed after the trade is done because settlement has to take place. Unlike dealers, brokers do not take positions and receive a broker fee for the transactions they acted as brokers.

[In one of my future posts, I will cover settlements of international trades because I believe the concept of settlement goes into the heart of the question: What Is Money.]

This leads to a multiplier effect, since the second dealer also may have excess inventory and this explains the high turnover in the fx markets. In an article Mark Flood from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Market Structure and Inefficiency in the Foreign Exchange Market, 1994, wrote:

The large volume of interbank trading is not primarily speculative in nature, but rather represents the tedious task of passing undesired positions along until they happen upon a marketmaker whose inventory discrepancy they neutralize.

The whole process is a bit haphazard way of shifting risk back to their customers!