There was a discussion last week on a social network site on Basil Moore’s book Horizontalists And Verticalists. Someone mentioned he never knew anyone who owned a copy of the book! Lucky me.

I was browsing through my copy and came across this – which I thought I should quote on central bank “defensive behaviour”.

Actually, among Post-Keynesians, Alfred Eichner was the first to understand and highlight the “defensive” nature of central bank open market operations.

Outside PKE, it was a paper of Raymond E. Lombra and Raymond G. Torto titled Federal Reserve Defensive Behaviour And The Reverse Causation Argument which started analyzing the details of the Federal Reserve defensive behaviour and supported the theory of endogenous money on which economists such as James Tobin and Nicholas Kaldor were writing at the time. The term “defensive” was coined by Robert Roosa of the Federal Reserve in the book Federal Reserve Operations In The Money And Government Securities Markets originally written in 1956.

Recently central banks around the world have been doing a lot of things (“unconventional measures”) in trying to “boost” their economies – such as “large scale asset purchases” (QE). For some, recent central bank action is the natural way to start to understand monetary economics. For me, it is first important to understand what they did before the crisis to correctly understand what they have been doing and judge if their actions have any usefulness at all – on a case by case basis.

Anyways, here is from Basil Moore’s book (pages 97-99):

Open-market operations: defensive rather than dynamic?

According to the conventional story taught in most textbooks and worked through by students in countless T-account exercises, central bank open-market security purchases have expansionary effects on the money stock by raising the high-powered base. Central bank security sales conversely lower the high-powered base, and so operate to reduce the stock of money outstanding.

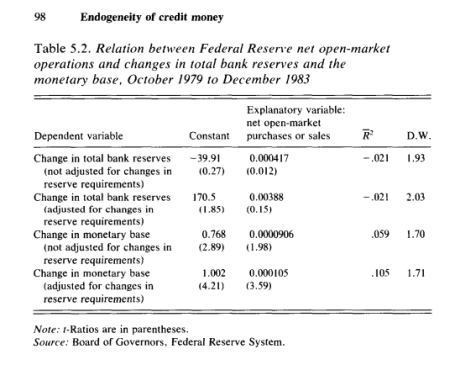

Table 5.2 presents the relationship between changes in total bank reserves, the monetary base, and the Federal Reserve net open-market security purchases or sales. The data are monthly time intervals for the period October 1979 to December 1983. This is the period when quantitative targeting was purportedly at last rigorously instituted. Nonborrowed reserves were avowedly the Fed’s chief operating instrument for controlling the growth rate of the monetary aggregates.

To the student of introductory economics, and even to many economists, these results will surely be startling. On a monthly basis, Federal Reserve net open-market operations fail to explain any of the actual changes in unadjusted or adjusted total reserves! They explain only 5 percent of changes in the unadjusted and only 10 percent of the changes in the high-powered base. In all cases the coefficient on net open-market purchases and sales is extremely small. It has no statistical significance in explaining observed changes in bank reserves. Although the coefficient is statistically significant in explaining the monetary base, its magnitude implies that $1000 of open-market purchases or sales were necessary to change the value of the base by $1!

The explanation for these apparently puzzling results is not far to seek (Lombra and Torto, 1973). From the central bank’s point of view a large number of stochastic nonpolicy factors operate to add or withdraw reserves from the banking system. These factors can be analyzed by an examination of the central bank’s balance sheet identity. This documents the various financial flows that accompany any change in the base: changes in float, changes in the public’s currency holding, foreign capital inflows or outflows, changes in treasury balances held with the Fed, changes in bank borrowing from the discount window. All of these flows are completely outside the control of the monetary authorities. In order to achieve a desired level of the base, these flows must be completely offset by open-market operations.

If the Fed were to take no action in the face of these large stochastic inflows and outflows of funds, the banking system would experience sharp fluctuations in its excess reserve position. Such changes would be unrelated to the Federal Reserve’s policy intentions, and would provoke continued liquidity crises and great instability in interest rates. As a result most Federal Reserve open-market operations are “defensive” and designed to offset the effects of these nonpolicy forces. Central banks operate to make reserves available to the banking system on reasonably stable terms, from day to day and week to week.

Studies of Federal Reserve open-market operations have estimated that more than 85 per cent of Federal Reserve security purchases of [sic] sales are “defensive” (Lombra and Torto, 1973, Forman, Groves and Eichner, 1984). Such flexibility is needed to deal with the very large inherent volatility of money flows. On a week-to-week basis such “noise” in the behaviour of the narrow money supply accounts for dollar changes in reserves of plus or minus $3 billion more than two-thirds of the time. This represents nearly 10 percent of total reserves, which were concurrently in the order of $40 billion (J. Pierce, 1982). On a monthly bias, such “noise” accounts for changes in the money stock or plus or minus 5 percent about two-thirds of the time.