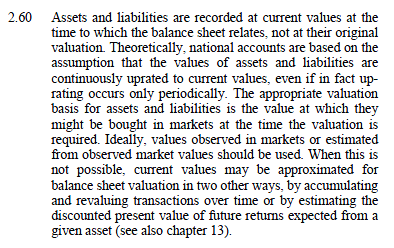

In the previous two posts, I went into a description of the transactions flow matrix and the balance sheet matrix as tools for an analytic study of a dynamical study of an economy.

During an accounting period, sectors in an economy are making all kinds of transactions. These can be divided into two kinds:

- Income and Expenditure Flows

- Financing Flows

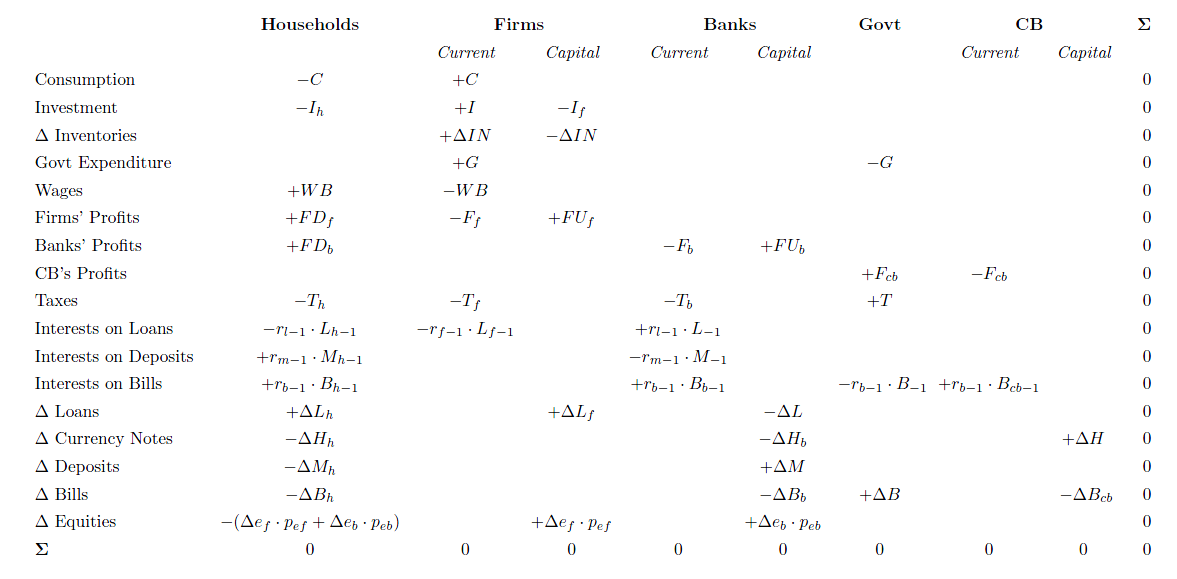

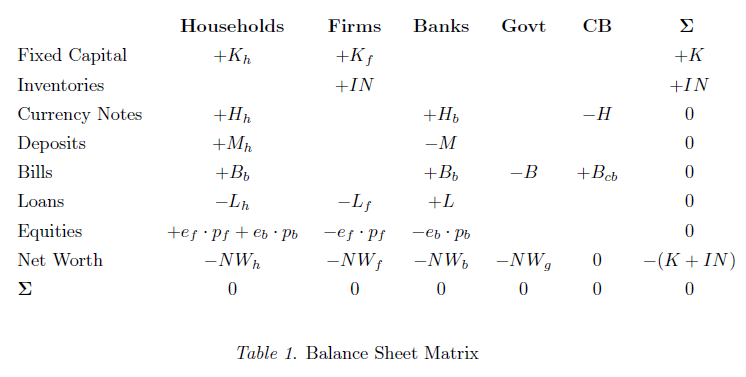

Let’s have the transactions flow matrix as ready reference for the discussion below.

(Click for a nicer view in a new tab)

The matrix can easily be split into two – on top we have rows such as consumption, government expenditure and so on and in the bottom, we have items which have a “Δ” such as “Δ Loans” or “change in loans”. We shall call the former income and expenditure flows and the latter financing flows.

To get a better grip on the concept, let us describe household behaviour in an economy. Households receive wages (+WB) and dividends from production firms (called “firms” in the table) and banks (+FD_{f} and +FD_{b}) respectively) on their holdings of stock market equities. They also receive interest income from their bank deposits and government bills. These are sources of households’ income. While receiving income, they are paying taxes and consuming a part of their income (and wealth). They may also make other expenditure such as buying a house or a car. We call these income and expenditure flows.

Due to these decisions, they are either left with a surplus of funds or a deficit. Since we have clubbed all households into one sector, it is possible that some households are left with a surplus of funds and others are in deficit. Those who are in surplus, will allocate their funds into deposits, government bills and equities of production firms and banks. Those who are in deficit, will need funds and finance this by borrowing from the banking system. In addition, they may finance it by selling their existing holding of deposits, bills and equities. The rows with a “Δ” in the bottom part of transactions flow matrix capture these transactions. These flows will be called financing flows.

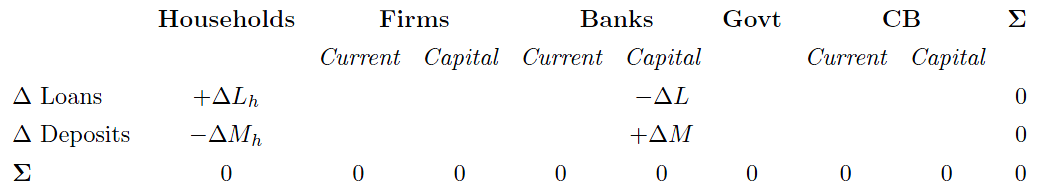

How do banks provide credit to households? Remember “loans make deposits”. See this thread Horizontalism for more on this.

This can be seen easily with the help of the transactions flow matrix!

The two tables are some modified version of tables from the book Monetary Economics by Wynne Godley and Marc Lavoie.

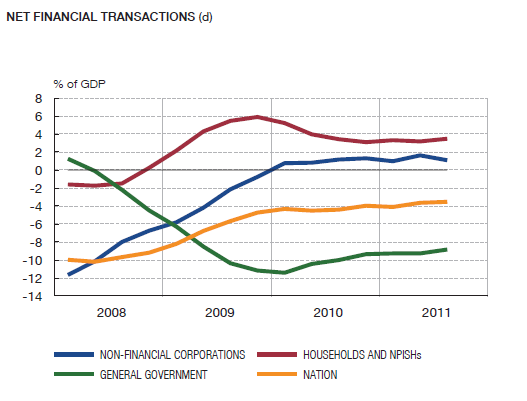

It is useful to define the flows NAFA, NIL and NL – Net Accumulation of Financial Assets, Net Incurrence of Liabilities and Net Lending, respectively.

If households’ income is higher than expenditure, they are net lenders to the rest of the world. The difference between income and expenditure is called Net Lending. If it is the other way around, they are net borrowers. We can use net borrowing or simply say that net lending is negative. Now, it’s possible and typically the case that if households are acquiring financial assets and incurring liabilities. So if their net lending is $10, it is possible they acquire financial assets worth $15 and borrow $5.

So the the identity relating the three flows is:

NL = NAFA – NIL

I have an example on this toward the end of this post.

I have kept the phrase “net” loosely defined, because it can be used in two senses. Also, some authors use NAFA when they actually mean NL – because previous system of accounts used this terminology as clarified by Claudio Dos Santos. I prefer old NAFA over NL, because it is suggestive of a dynamic, though the example at the end uses the 2008 SNA terminology.

While households acquire financial assets and incur liabilities, their balance sheets are changing. At the same time, they also see holding gains or losses in their portfolio of assets. What was still missing was a full integration matrix but that will be a topic for a post later. Since, it is important however, let me write a brief mnemonic:

Closing Stocks = Opening Stocks + Flows + Revaluations

where revaluations denotes holding gains or losses.

This is needed for all assets and liabilities and for all sectors and hence we need a full matrix.

We will discuss more on the behaviour of banks (and the financial system) and production firms some other time but let us briefly look at the government’s finances.

As we saw in the post Sources And Uses Of Funds, government’s expenditure is use of funds and the sources for funds is taxes, the central bank’s profits, and issue of bills (and bonds). Unlike households, however, the government is in a supreme position in the process of “money creation”. Except with notable exceptions such as in the Euro Area, the government has the power to make a draft at the central bank under extreme emergency, though ordinarily it is restricted. Wynne Godley and Francis Cripps described it as follows in their 1983 book Macroeconomics:

Our closed economy has a ‘central bank’ with two principle functions – to manage the government’s debt and to administer monetary policy. [Footnote: The central bank has to fund the government’s operations but this in itself presents no problems. Government cheques are universally accepted. When deposited with commercial banks the cheque become ‘reserve assets’ in the first instance; banks may immediately get rid of excess reserve assets by buying bonds.]. The only instrument of monetary policy available to the central bank in our simple system is the buying and selling of government bonds in the bond market. These operations are called open market operations. We assume that the central bank does not have the right to directly intervene directly in the affairs of commercial banks (e.g., to prescribe interest rates or quantitative lending limits) or to change the 10% minimum reserve requirement. But the central bank is in a very strong position in the bond market since it can sell or buy back bonds virtually without limit. This gives it the power, if it chooses, to fix bond prices and yields unilaterally at any level [Footnote: But speculation based on expectations of future yields may oblige the central bank to deal on a very large scale to achieve this objective.] and thereby (as we shall soon see) determine the general level of interest rates in the commercial banking system.

Given such powers, we can assume in many descriptions that the government’s expenditure and the tax rate is exogenous. However, many times, there are many constraints such as price and wage rises, high capacity utilization and low production capacity and also constraints brought about from the external sector due to which fiscal policy has to give in and become endogenous.

While I haven’t introduced open economy macroeconomics in this blog in a stock-flow coherent framework, we can make some general observations:

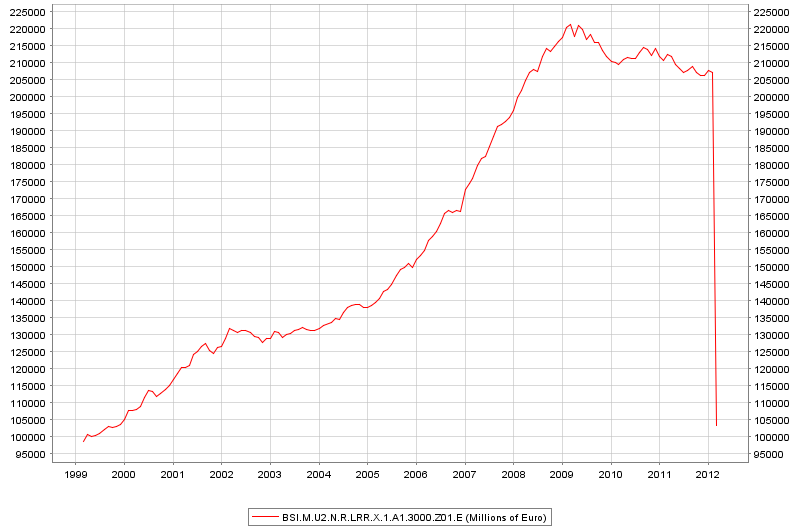

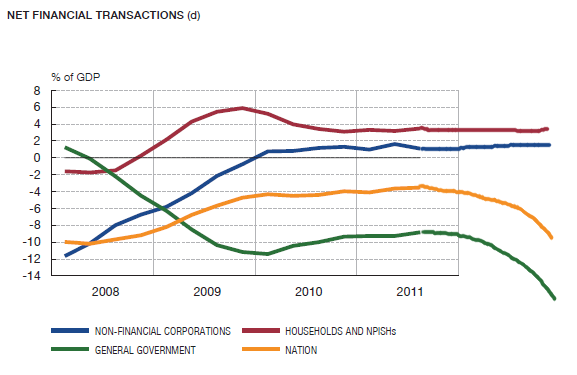

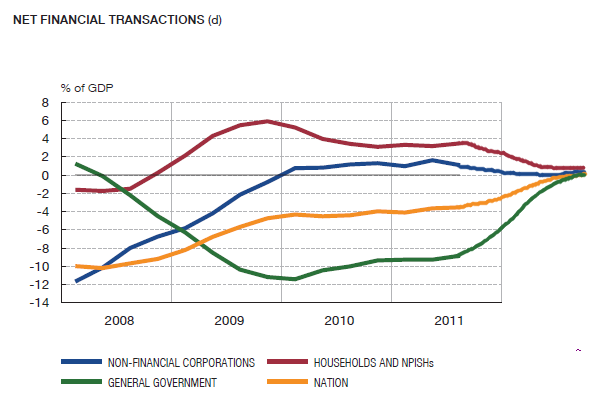

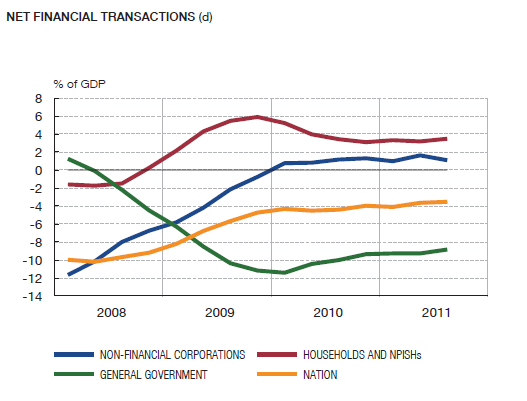

For a closed economy as a whole, income = expenditure. While it is true for the whole economy (worth stressing again: closed), it is not true for individual sectors. The household sector, for example, typically has its income higher than expenditure. In the last 15-20 years, even this has not been the case. If one sector has it’s income higher than expenditure, some sectors in the rest of the world will have its income lower than its expenditure. Many times, the government has its income lower than expenditure and we see misleading public debates on why the government should aim to achieve a balanced budget. When a sector has its income lesser than expenditure, it’s net lending is negative and hence is a net borrower from the rest of the world. It can finance this by borrowing or sale of assets. A region or a whole nation can have its expenditure higher than income and this is financed by borrowing from the rest of the world. A negative flow of net lending implies a net incurrence of liabilities – thus adding to the stock of net indebtedness which can run into an unsustainable territory. Stock-flow coherent Keynesian models have the power to go beyond short-run Keynesian analysis and study sustainable and unsustainable processes.

In an article Peering Over The Edge Of The Short Period – The Keynesian Roots Of Stock-Flow Consistent Macroeconomic Models, the authors Antonio C. Macedo e Silva and Claudio H. Dos Santos say:

… it is important to have in mind that it is possible to get three kinds of trajectories with SFC models:

- trajectories toward a sustainable steady state;

- trajectories toward a steady state over certain limits;

- explosive trajectories.

The analysis of SFC models’ dynamic trajectories and steady states is useful, first because it makes clear to the analyst whether the regime described in the model is sustainable or whether it leads to some kind of rupture—either because the trajectory is explosive or because it leads to politically unacceptable configurations. In these cases, as Keynes would say in the Tract, the analyst can conclude that something will have to change and even get clues about (i) what will probably change (since the sensitivity of the system dynamics to changes in different behavioural parameters is not the same); and (ii) when this change will occur (since the system may converge or diverge more or less rapidly).

Example

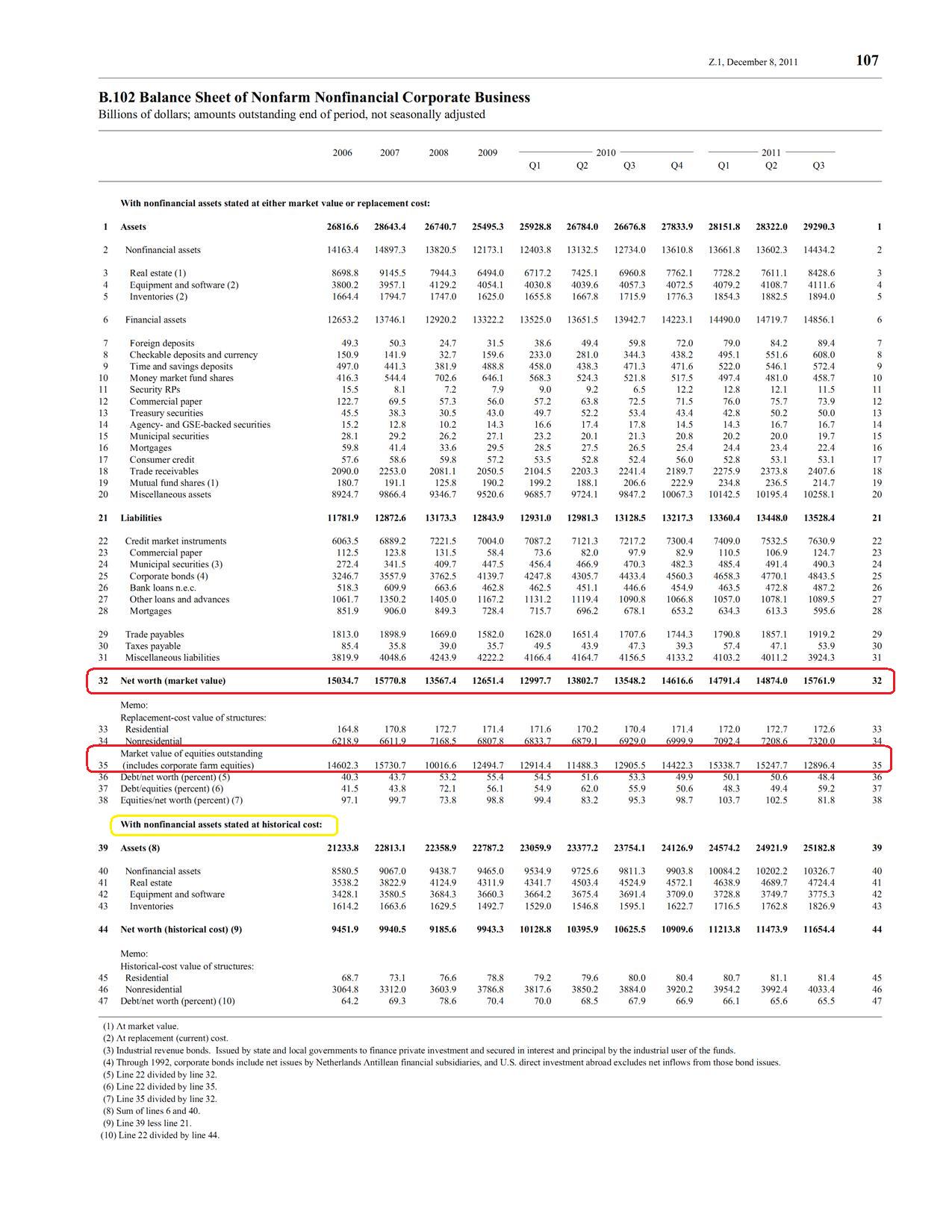

Note that Net Lending is different from “saving”. Say, a household earns $100 in a year (including interest payments and dividends), pays taxes of $20 and consumes $75 and takes a loan of to finance a house purchase near the end of the year whose price is $500. Assume that the Loan-To-Value (LTV) of the loan is 90% – which means he gets a loan of $450 and has to pay the remaining $50 from his pocket to buy the house. (i.e., he is financing the house mainly by borrowing and partly by sale of assets). How does the bank lending – simply by expanding it’s balance sheet (“loans make deposits”). Ignoring, interest and principal payments (which we assume to fall in the next accounting period),

His saving is +$100 – $20 – $75 = +$5.

His Investment is +$500.

His Net Incurrence of Liabilities is +$450.

His Net Accumulation of Financial Assets is +$5 – $50 = – $45.

His Net Lending is = -$45 – (+$450) = -$495 which is Saving net of Investment ($5 minus $500).

This means even though the person has “saved” $5, he has incurred an additional liability of $450 and due to sale of assets worth $45, he is a net borrower of $495 from other sectors (i.e., his net lending is -$495).

Assume he started with a net worth of $200.

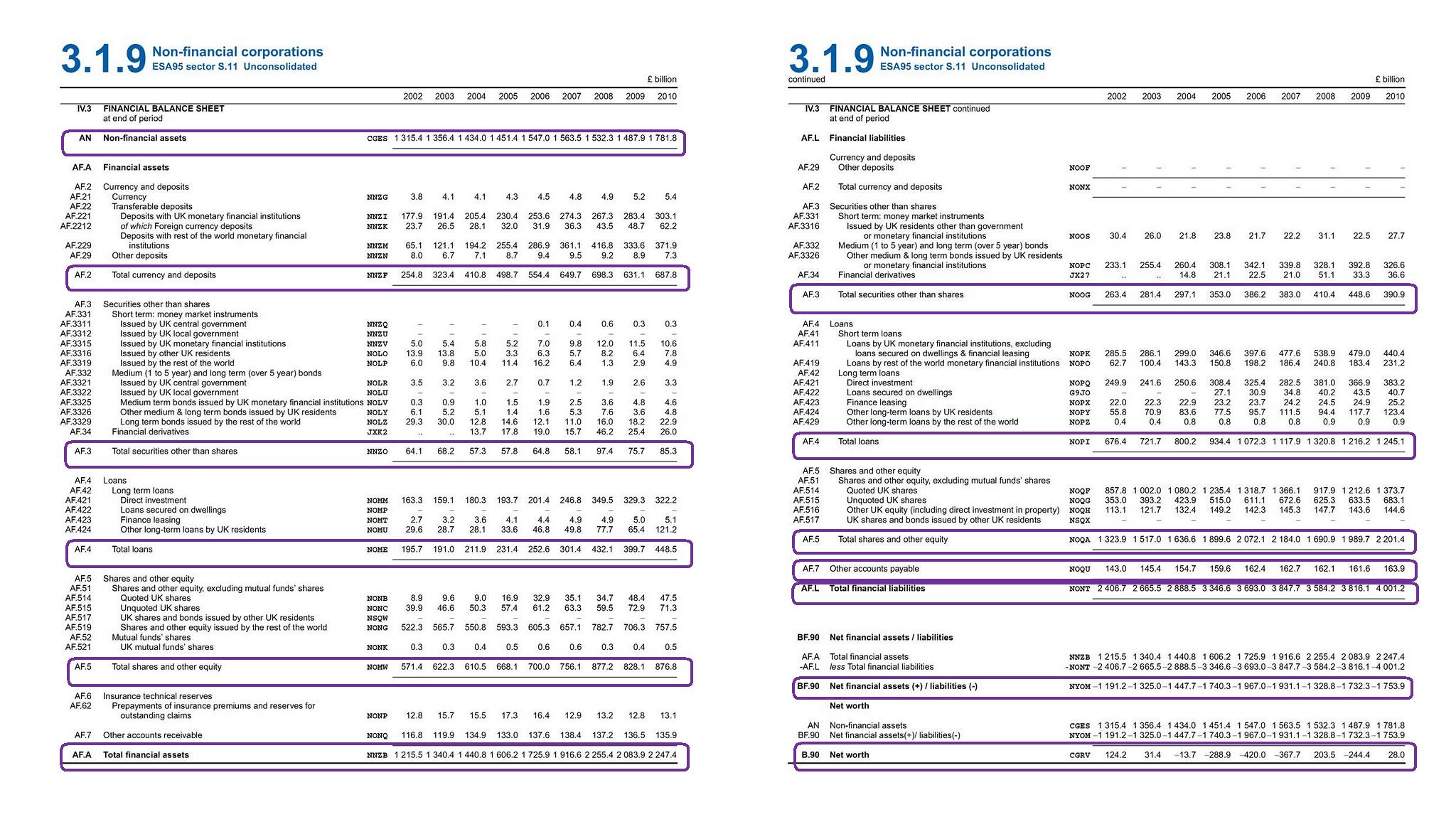

| Opening Stocks: 2010 | $ |

| Assets | 200 |

| Nonfinancial Assets Deposits Equities | 0 |

| Liabilities and Net Worth | 200 |

| Loans Net Worth | 0 |

Now as per our description above, the person has a saving of $5 and he purchases a house worth $500 by taking a loan of $450 and selling assets worth $50. We saw that the person’s Net Accumulation of financial assets is minus $45. How does he allocate this? (Or unallocate $45)? We assume a withdrawal of $10 of deposits and equities worth $35. At the same time, during the period, assume he had a holding gain of $20 in his equities due to a rise in stock markets.

Hence his deposits reduce by $10 from $30 to $20. His holding of equities decreases by $15 (-$35 + $20 = -$15)

How does his end of period balance sheet look like? (We assume as mentioned before that the purchase of the house occurred near the end of the accounting period, so that principal and interest payments complications appear in the next quarter.)

| Closing Stocks: 2010 | $ |

| Assets | 675 |

| Nonfinancial Assets Deposits Equities | 500 |

| Liabilities and Net Worth | 675 |

| Loans Net Worth | 450 |

Just to check: Saving and capital gains added $5 and $20 to his net worth and hence his net worth increased to $225 from $200.

Of course, from the analysis which was mainly to establish the connections between stocks and flows seems insufficient to address what can go wrong if anything can go wrong. In the above example, the household’s net worth gained even though he was incurring a huge liability. What role does fiscal policy have? The above is not sufficient to answer this. Hence a more behavioural analysis for the whole economy is needed which is what stock-flow consistent modeling is about.

One immediate answer that may satisfy the reader now is that the households’ financial assets versus liabilities has somewhat deteriorated and hence increased his financial fragility. By running a deficit of $495 i.e., 495% of his income, the person and his lender has contributed to risk. Of course, this is just one time for the person – he may be highly creditworthy and his deficit spending is an injection of demand which is good for the whole economy. After all, economies run on credit. While this person is a huge deficit spender, there are other households who are in surplus and this can cancel out. In the last 15 years or so, however (before the financial crisis hit), households (as a sector) in many advanced economies ran deficits of the order of a few percentage of GDP. If the whole household sector continues to be a net borrower for many periods, then this process can turn unsustainable as the financial crisis in the US proved.

Now to the title of the post. Flows such as consumption, taxes, investment are income/expenditure flows. Flows such as “Δ Loans”, “Δ Deposits”, “Δ Equities” are financing flows. Income/expenditure flows affect financing flows which then affect balance sheets, as we see in the example.