Beate Reszat has written a very nice article on TARGET2 Target2 – Q&A which should be read by anyone interested. The article seems to be in response to a speech by George Soros earlier this month in Italy. The link appears in her post and the relevant section of the transcript quoted.

Although it is a very informative article, I think the writer gives a misleading picture by disagreeing with George Soros.

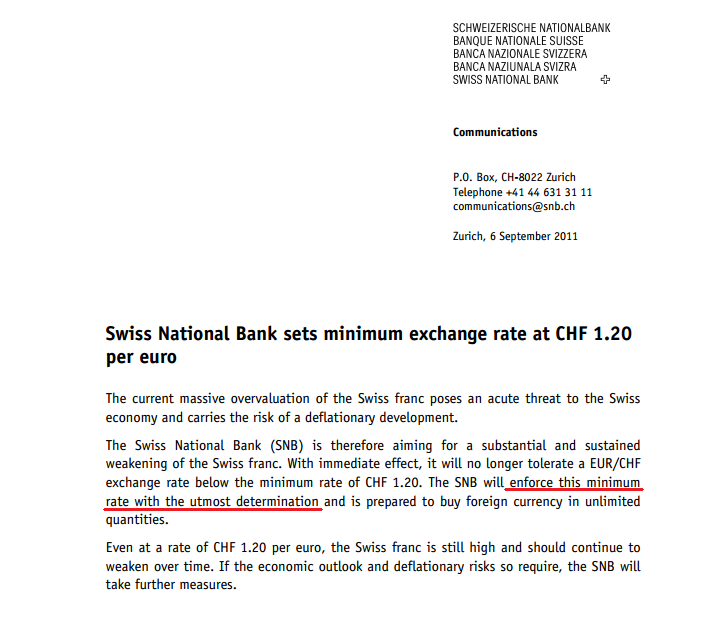

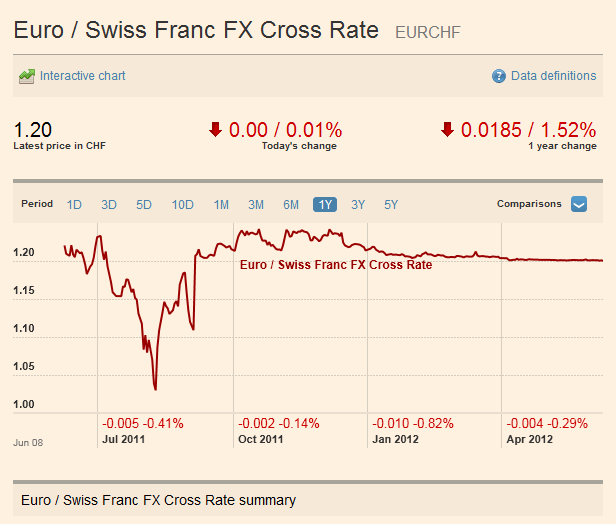

For a background, the whole debate started when a German Professor Hans-Werner Sinn wrote an article The ECB’s Stealth Bailout which led to a series of attacks from academicians to bankers to central banks seriously questioning Sinn. Sinn’s arguments are full of errors but this brought into focus the TARGET2 claims of creditor nations’ NCBs and the risks that this asset may “disappear”.

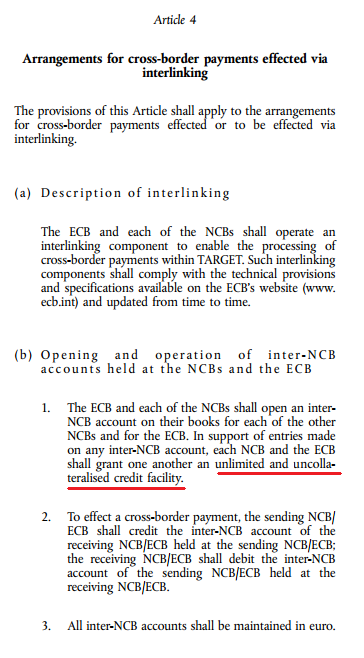

Critics of Sinn learned the TARGET system and to my surprise, their description had a lot of features on money endogeneity – surprising since most of these writers err on describing one pole (of the two poles) of money endogeneity – that between banks and their central bank.

In the end, the critics claimed victory – although powerful persons such as George Soros and Jen Weidmann of Bundesbank understood and saw the situation slightly differently. Even Martin Wolf who has differences with Weidmann on the German economic strategy – rightly in my view – agrees that it may lead to losses to Germany in case of debtor nations leaving the Euro Area.

(By the way this link by Robert M Wuner has the complete list of articles on the TARGET2 debate).

Now, I have myself written a set of articles on this: The Eurosystem: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, & Part 5.

On the specific issue about creditor nations taking a loss see this post: Who Is Germany and Deutsche Bundesbank’s TARGET2 Claims.

While it is difficult to summarize the whole debate, the point which comes to mind is that while those who have written about the TARGET2 system in a more technically correct way (central bank articles, banks’ research publications, academicians), they are seriously misleading. Some don’t see it while – in my opinion – the Eurosystem authors see it and downplay the risks.

So here’s from Beate’s article:

If the country in question refrains from staying connected to Target2 and, at the same time, is abandoning the ECB – in my understanding (but we must ask the jurists to find out) its paid-up capital will have to be returned plus its share of profit, or minus its share of loss according to a consolidated closing balance sheet and profit and loss statement.

Now this is serious underplay. She concludes:

The way the issue of Target2 balances is discussed in public is most regrettable. The ever new records of unmanageable bilateral debt allegedly heaping up in the system arouse fears which are wholly unreasonable and stand in the way to finding a viable crisis solution. Two points should be kept in mind: Monetary policy matters such as the creation of central bank money must not be confused with the process of payment and settlement of central bank money, and intra-group payment flows as part of the normal business of the system must not be confused with profits and losses.

At closer inspection, the €2 trillion debt scenario conjured up by some observers in an utterly irresponsible way is evaporating into thin air and the euro crisis – although still a very serious problem and a big challenge – appears as one that probably can be handled.

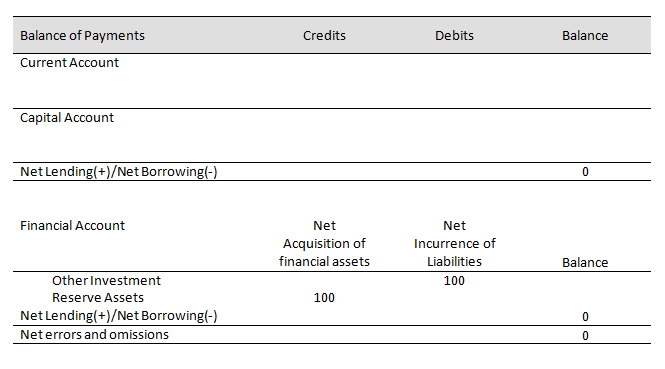

The error in analysis such as this is that of not thinking of “money” as simultaneously as an asset and a liability.

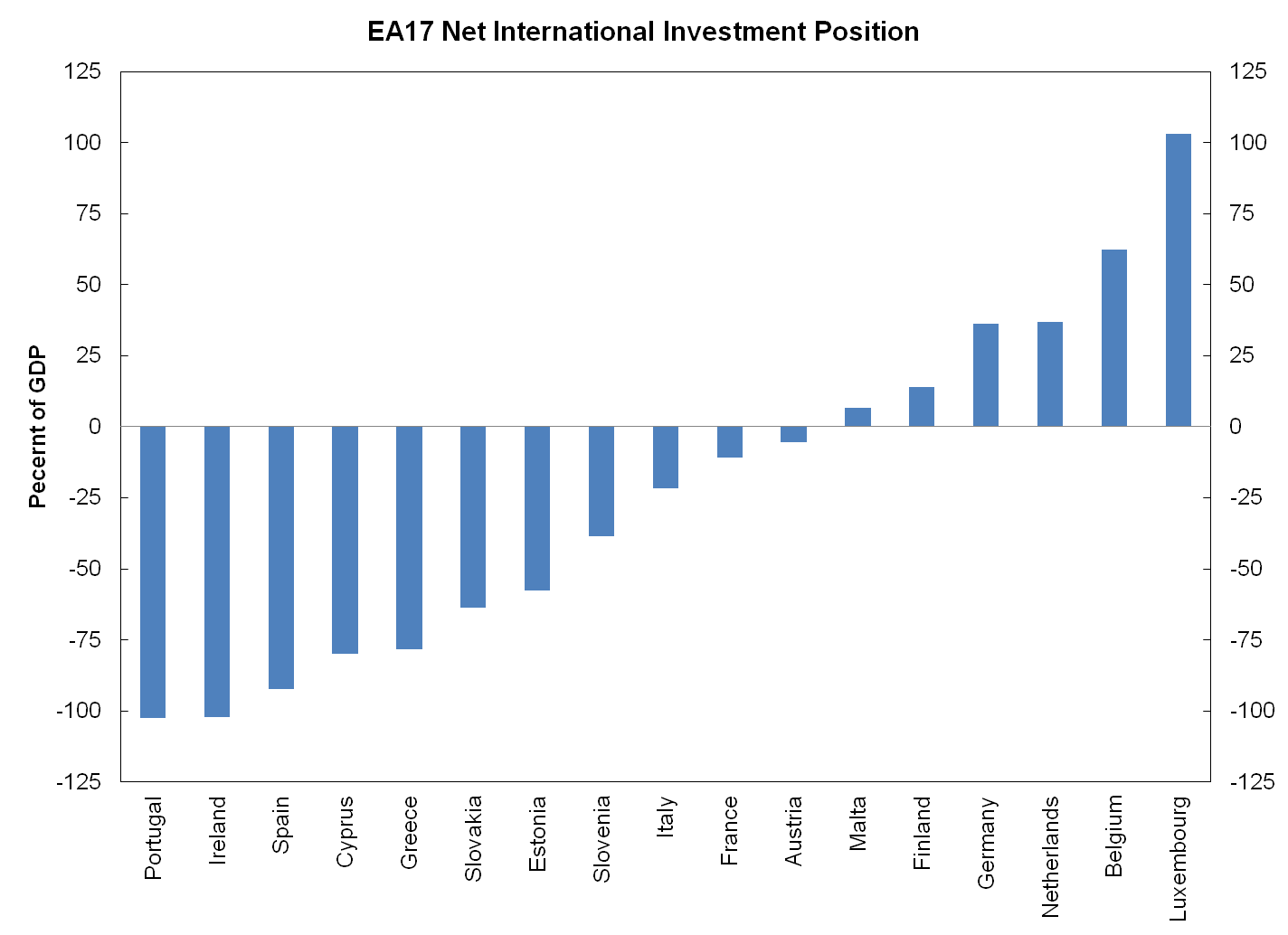

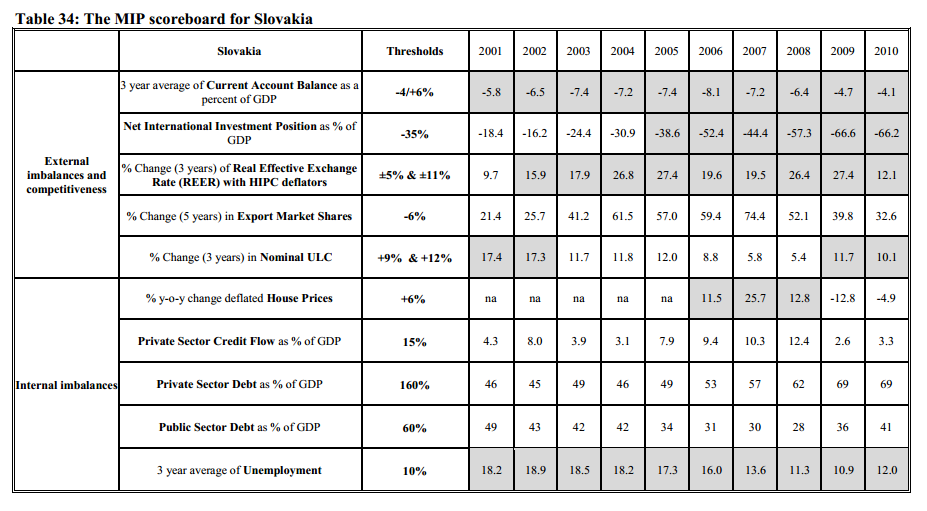

It is best to think of the creditor nations as a whole so that the complication of “capital key” can be avoided. In my post Who Is Germany I argue that the exit of debtor members of the Euro Area will lead to losses for the creditor nations because the debtor nations will not be able to pay the Euro-denominated TARGET2 liabilities. This appears via a direct loss on the central banks’ balance sheet. And since this is a loss of the balance sheet of a nation (or a group of nations as a whole), it is plainly incorrect to argue that it does not matter or that Soros is wrong. The complication of “capital key” is a bit of a sideshow – if Germany’s losses are less than its TARGET2 claims, other NCBs lose. It is true that the Bundesbank may be capitalized by the German government – in case – but no amount of domestic transaction can change the external assets (of Germany as a whole). The fact that it is a loss to Germany can be seen by looking at the International Investment Position. If the Bundebank loses its TARGET claims, it is a loss for the whole nation. As the chapter 7 of the IMF’s Balance Of Payments And International Investment Position Manual (BPM6) says:

The IIP is a subset of the national balance sheet. The net IIP plus the value of nonfinancial assets equals the net worth of the economy, which is the balancing item of the national balance sheet.

In fact, George Soros’ argument is that since exits of debtor nations from the Euro Area will lead to serious losses to creditor nations, this has the effect of forcing the latter – especially Germany – to do something and in fact in leading them to move toward higher integration! (as a title of his recent article The Accidental Empire from Project Syndicate suggests).

To the point of Beate Reszat’s dislike for the phrase – “evaporating in thin air”, the BPM6 and the 2008 SNA use similar terminology – “appearance and disappearance of assets”!

Marc Lavoie at the Levy Institute, May 2011 (Photo Credits: me 😉 )

Marc Lavoie at the Levy Institute, May 2011 (Photo Credits: me 😉 )