[Although the following is a response aimed at one comment, it can be read in general]

In my post on the connection between balance of payments and debt sustainability, I got a “you are wrong” comment saying the analysis is based on the notion of trade elasticities which doesn’t exist (or is a chimerical notion) and that I ignore floating exchange rates. So a reply.

Trade Elasticities

A standard observation is that imports and exports depend on income – domestic and in the rest of the world. Exports depend on how competitive the producers are in the rest of the world and also the demand in the rest of the world. Similarly imports depend on foreign producers’ competitiveness compared to domestic producers as well as domestic demand. So in a simple Keynesian model one writes:

IM = μY

where μ is the propensity to import. It measures imports as a proportion of domestic output. Relative propensities (between nations) measure relative competitiveness of producers. This is a very quick way to build a model for how stocks and flows change over time.

There is one simplification in this. Although it rightly captures the amount of imports during a period – such as a few years, it supposes imports rise one-to-one with output – i.e.,

ΔIM/IM = ΔY/Y

But in reality it could be worse – as the response of imports to a rise in domestic demand can be worse.

Also, it doesn’t capture the effect of prices. Producers across the world compete with each other on both the quality of their products and on price. So we have “non-price competitiveness” and “price competitiveness” . Now it is a Post-Keynesian observation that non-price competitiveness is much more important. So one has income elasticity of imports as well as price elasticity and the analysis can get a bit complicated. Some kinds of products have higher elasticities than others. For example manufactured products may have different elasticities as compared to raw materials, commodities etc. Also one can include nuances such as which is more important – income, expenditure, output etc.

Even more generally, the rest of the world consists of many nations and one has to be careful. So the rest of the world may be growing but it may happen that exports aren’t because exports are concentrated on one country or a group of nations which are not growing.

A good original reference is Joan Robinson’s article The Foreign Exchanges from her 1937 book Essays In The Theory Of Employment.

Rather than going through the analysis, let me just show the plot of the United States’ imports to show that the concept of elasticity is far from chimerical as one observer claims.

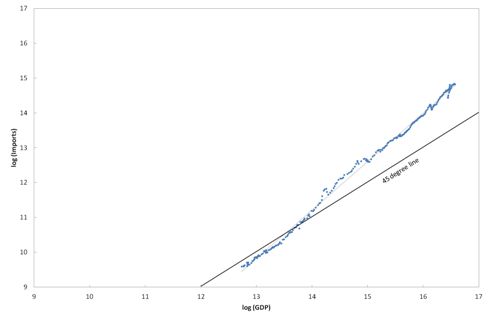

The following is a scatter-plot of the logarithms of GDP and Imports for the United States since 1951 (quarterly). The data is from Federal Reserve’s Z.1 Flow of Funds Accounts.

The thin grey line is the fit and in addition, there is a 45-degree line to show that the slope is different than 1.

The “elasticity” is supposed to capture the response of imports to a rise in expenditure/income/output. The above simple scatter-plot shows the relation is far from being random.

So much for the notion that trade elasticities don’t exist!

Of course, the elasticities can be improved and not god-given. A nation’s government can take some protection and/or invest in research and development because the elasticity is a supply-side concept. It can also be improved if producers learn how to improve their products and the quality of its sales force in marketing them in international markets. Still, the improvement depends on how well all these are carried out etc.

Now to floating exchanges.

Floating Exchange Rates

Now, it can be argued that a debt sustainability analysis is invalid because of floating exchange rates. If a nation’s currency floats, a depreciation of the exchange rate in the foreign exchange markets can improve the trade balance. While it is true that a depreciation can turn the balance in a nation’s favour because of price effects, it is doesn’t necessarily happen that way. Even if one assumes away J-curve effects, a nation can find itself in a balance worsening in spite of a depreciation. This is because non-price competitiveness is far more important than price-competitiveness. In fact there exists no reason how “market forces” miraculously resolve the imbalances by depreciating. In reality trade imbalances are kept from blowing up by adjustments to income.

It is one thing to say that depreciation can improve the trade balance (which has truth to it) and another to say it can do a miracle.

Now, coming to debt sustainability, one can still claim that this process can continue forever (i.e., net indebtedness to foreigners rising forever relative to gdp) without any trouble in the foreign exchange markets. That is something for another post but it is too much of a claim.

The Joan Robinson paper I quoted has the mechanism of how this ends up creating troubles in the fx markets.