This looks nice but will be released only in May 🙁

Table of Contents

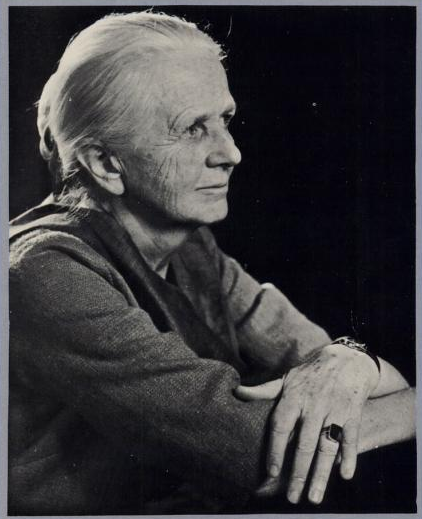

Preface and acknowledgements

Introduction – G.C. Harcourt and Peter Kriesler

1. A personal view of the origins of post-Keynesian ideas in the history of economics – Jan Kregel

2. Sraffa, Keynes and post-Keynesianism – Heinz Kurz

3. Sraffa, Keynes and post-Keynesians: Suggestions for a synthesis in the making – Richard Arena and Stephanie Blankenburg

4. On the notion of equilibrium or the centre of gravitation in economic theory – Ajit Sinha

5. Keynesian foundations of post-Keynesian economics – Paul Davidson

6. Money – Randall Wray

7. Post-Keynesian theories of money and credit: conflict and (some) resolutions – Victoria Chick and Sheila Dow

8. The scientific illusion of New Keynesian monetary theory – Colin Rogers

9. Single period analysis and continuation analysis of endogenous money: a revisitation of the debate between horizontalists and structuralists – Giuseppe Fontana

10. Post-Keynesian monetary economics Godley-like – Marc Lavoie

11. Hyman Minsky and the financial instability hypothesis – John King

12. Endogenous growth: A Kaldorian approach – Mark Setterfield

13. Structural economic dynamics and the Cambridge tradition – Prue Kerr and Robert Scazzieri

14. The Cambridge post-Keynesian school of income and wealth distribution – Mauro Baranzini and Amalia Mirante

15. Reinventing macroeconomics – Edward Nell

16. Long-run growth in open economies: export-led cumulative causation or a balance-of-payments constraint? – Robert Blecker

17. Post-Keynesian precepts for nonlinear, endogenous, nonstochastic, business cycle theories – K. Vela Velupillai

18. Post-Keynesian approaches to industrial pricing: a survey and critique – Ken Coutts and Neville Norman

19. Post-Keynesian price theory: from pricing to market governance to the economy as a whole – Frederic S. Lee

20. Kaleckian economics – Robert Dixon and Jan Toporowski

21. Wages policy – John King

22. Discrimination in the labour markets – Peter Riach and Judith Rich

23. Post-Keynesian perspectives on economic development and growth – Peter Kriesler

24. Keynes and economic development – Tony Thirlwall

25. Post-Keynesian economics and the role of aggregate demand in less-developed economies – Amitava Krishna Dutt

—

Volume 2 website here

Table of Contents

Preface and acknowledgements

Introduction (from volume 1) – G.C. Harcourt and Peter Kriesler

1. On microfoundations of macroeconomics – Abu Rizvi

2. Post-Keynesian economics, rationality and conventions – Tom Boylan and Paschal O’Gorman

3. Methodology and post-Keynesian economics. – Sheila Dow

4. Critiques, methodology and the relationship of post-Keynesianism to other heterodox approaches – Gay Meeks

5. Two post-Keynesian approaches to uncertainty and irreducible uncertainty – Rod O’Donnell

6. The interdisciplinary applications of post-Keynesian economics – Wylie Bradford

7. Post-Keynesian economics, critical realism and social ontology – Stephen Pratten

8. The traverse, equilibrium analysis and post-Keynesian economics – Joseph Halevi, Neil Hart and Peter Kriesler

9. A personal view of post-Keynesian elements in the development of economic complexity theory and its application to policy – Barclay Rosser Jr.

10. How sound are the foundations of the aggregate production function? – Jesus Felipe and John McCombie

11. Marx and post-Keynesians – Claudio Sardoni

12. The L-shaped aggregate supply curve, the Phillips curve, and the future of macroeconomics – James Forder

13. A post-Keynesian critique of independent central banking – Joerg Bibow

14. The post-Keynesian critique of the mainstream theory of the state and the post-Keynesian approaches to economic policy – Richard Holt

15. A modern Kaleckian-Keynesian framework for economic theory and policy – Philip Arestis and Malcolm Sawyer

16. Classical-Keynesian political economy: genesis, present state and implications for political philosophy and economic policy – Heinrich Bortis

17. Post-Keynesian distribution of personal income and policy – James K. Galbraith

18. Environmental economics – Neil Perry

19. Theorising about post-Keynesian economics in Australasia: aggregate demand, economic growth and income distribution policy – Paul Dalziel and J. W. Nevile

20. The heterodox spiral and the neoclassical sink: reclaiming economic theory after neo-liberalism – Gary Dymski

21. Keynesianism and the crisis – Lance Taylor