‘The rate of growth (y) of any developed country in the long run is equal to the growth rate of the volume of its exports (x) divided by its income elasticity of demand for imports (π)’, he [Anthony Thirlwall] explained.

Our eyes were fixed on the blackboard, attempting to digest the meaning and internalize the implications of this tri-legged animal. That job was not easy. For the animal distilled volumes of legendary work in economic development, encapsulating all of them in a small-sized anti-underdevelopment pill. The teaching of Engel’s law, which implies that the demand for primary goods increases less than proportionally to increases in global income; the Harrod foreign trade multiplier which put forward the idea that the pace of industrial growth could be explained by the principle of the foreign trade multiplier; the Marshall– Lerner condition which implies that a currency devaluation would not be effective unless the devaluation-induced deterioration in the terms of trade is more than offset by the devaluation-induced reduction in the volume of imports and increase in volume of exports; the Hicks super-multiplier which implies that the growth rate of a country is fundamentally governed by the growth rate of its exports; the Prebisch–Singer hypothesis which asserts that a country’s international trade that depends on primary goods may inhibit rather than promote economic growth; the Verdoorn–Kaldorian notion that faster growth of output causes a faster growth of productivity, implying the existence of substantial economies of scale; Kaldor’s paradox which observed that countries that experienced the greatest decline in their price competitiveness in the post-war period experienced paradoxically an increase in their market share and not a decrease; the literature on export-led growth which asserts that export growth creates a virtuous circle through the link between output growth and productivity growth – all of these doctrines were somehow put into play and epitomized within this small-sized capsule. Not only that but the capsule was sealed by the novel and powerful ingredient of the balance-of-payments constraint: ‘in the long run, no country can grow faster than that rate consistent with balance of payments equilibrium on current account unless it can finance ever-growing deficits which, in general, it cannot’.

– Mohammed Nureldin Hussain, The Implications Of Thirlwall’s Law For Africa’s Development Challenges in Growth And Economic Development Essays In Honour Of A.P. Thirlwall, 2006

Monthly Archives: February 2016

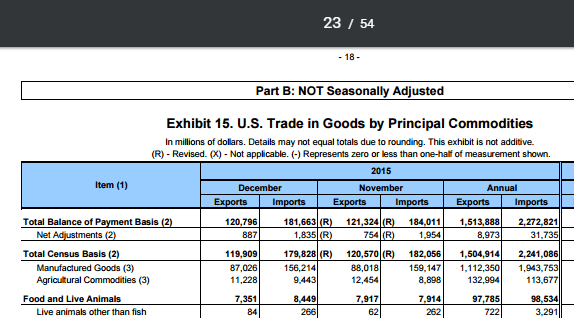

U.S. Manufacturing Deficit

The latest U.S. trade report is out and has data for the whole year 2015. Manufacturing deficit is something worth noting.

The U.S. manufacturing deficit is $831 bn.

U.S. Manufacturing Exports/Imports

It is sometimes said that manufacturing has lost its importance and that countries in balance of payments difficulties should look to trade in services to put things right. However, while it is still true that manufacturing output has declined substantially as a share of GDP, the figures quoted above show that the share of manufacturing imports has risen substantially. The importance of manufacturing does not reside in the quantity of domestic output and employment it generates, still less in any intrinsic superiority that production of goods has over provision of services; it resides, rather, in the potential that manufactures have for expansion in international trade.

– Wynne Godley, A Critical Imbalance In U.S. Trade, The U.S. Balance Of Payments, International Indebtedness, And Economic Policy, September 1995.

Kaldor’s Footnote And Kaldor On Sraffa

The world is more Kaldorian than Keynesian. After the crisis, Keynes became popular again but his Cambridge descendent Nicholas Kaldor is hardly remembered by the economics community. Even his biographers have some memory loss of him.

😉

Anthony Thirlwall and John E. King are biographers of Nicholas Kaldor. Superb books.

There’s a chapter Talking About Kaldor: An Interview With John King in Anthony Thirlwall’s book Essays on Keynesian and Kaldorian Economics. There’s an interesting discussion on money endogeneity (Google Books link):

J.E.K. … I wonder if Kaldor would have gone as far as Moore in arguing that the money supply curve is horizontal.

Anthony Thirlwall replies saying he would have argued that the supply of money is elastic with respect to demand, instead of quoting him. Here’s Nicholas Kaldor stating explicitly in a footnote in Keynesian Economics After Fifty Years, in the book, Keynes And The Modern World, ed. George David Norman Worswick and James Anthony Trevithick, Cambridge University Press, 1983, on page 36:

Diagrammatically, the difference in the presentation of the supply and demand for money, is that in the original version, (with M exogenous) the supply of money is represented by a vertical line, in the new version by a horizontal line, or a set of horizontal lines, representing different stances of monetary policy.

[italics: mine]

Anthony Thirlwall is one of the commenter in the book chapter. The book is proceedings of a conference on Keynes.

But that’s not enough. Turn to page 363 of the book.

A.P.T. He had a very high regard for Sraffa but he never wrote on this topic.

J.E.K. Not something that would really have concerned him very much? Too abstract and too removed from reality?

A.P.T. Probably, yes. It is quite interesting that Sraffa was his closest friend, both personal and intellectual, and they used to meet very regularly – almost every day when Sraffa was alive. But there’s no evidence that they ever discussed Production of Commodities by Means of Commodities.

J.E.K. That’s amazing. There’s certainly no evidence that he ever wrote anything on those questions.

A.P.T. There’s no evidence that he wrote anything, or that indeed he really understood Sraffa. Well, he had the broad thrust, but I don’t know that he ever read it carefully, or understood the implications.

In Volume 9, of Kaldor’s Collected Works, there are two memoirs. One of Piero Sraffa and the other on John von Neumann.

Nicholas Kaldor on Piero Sraffa

Interestingly the editors and F. Targetti (another biographer) and A.P. Thirlwall!

I guess if you know a person so closely – like the biographers do, of Kaldor- you tend to forget a few things about them.

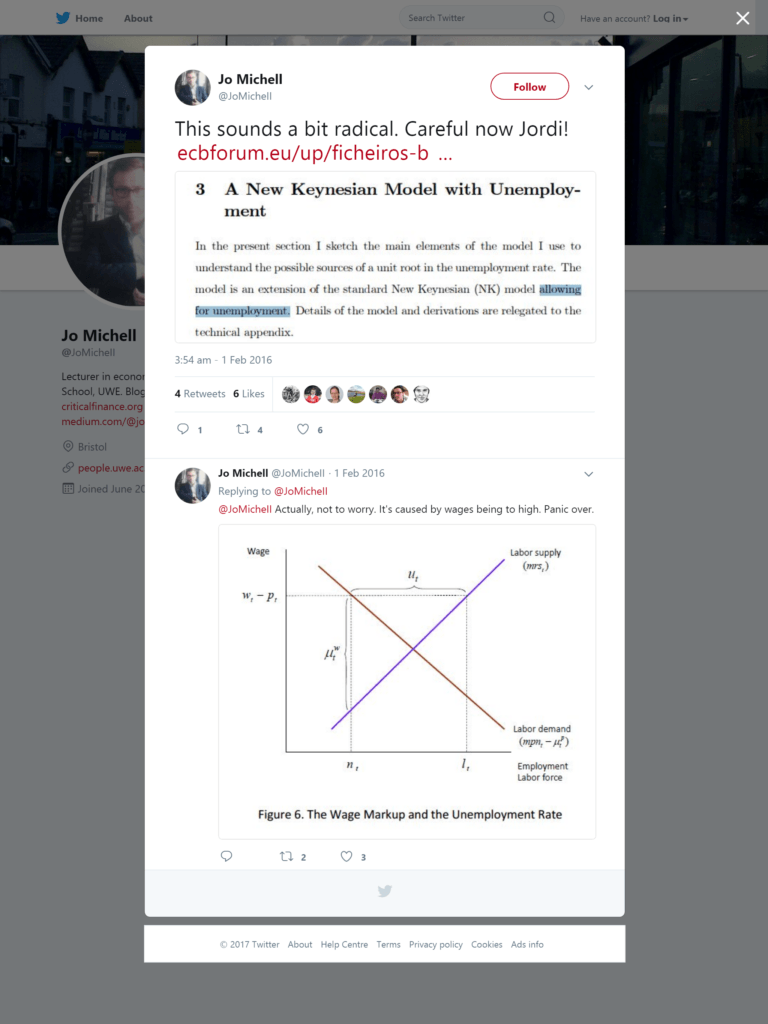

Nick ROKE, Thrift, And Hoarding

The new issue of ROKE is out and celebrates 80 years of The General Theory. Nick Rowe has a new paper in the issue titled, Keynesian Parables Of Thrift And Hoarding. Requires access. Nick has a post on his blog where he welcomes comments.

Abstract:

I argue that Keynes missed seeing the importance of the distinction between saving in the form of money (‘hoarding’) and saving in all other forms (‘thrift’). It is excessive hoarding, not excessive thrift, that causes recessions and the failure of Say’s law. The same failure to distinguish hoarding from thrift continues from The General Theory into the IS–LM model and into New Keynesian macroeconomics. On this particular question, economists should follow Silvio Gesell rather than John Maynard Keynes. The rate of interest in New Keynesian models should be interpreted as a negative Gesellian tax (that is, a subsidy) on holding money issued by the central bank.

In my opinion, a part of it, the distinction between what’s called “hoarding” and “thrift” above is not something which Keynesians haven’t considered. In fact, in the sectoral balances approach, it is net lending and not saving whose behaviour is more highlighted.

A sector’s or an economic unit’s saving is defined as its disposable income less consumption expenditure.

S = YD − C

On the other hand, a sector’s net lending is defined as its disposable income less expenditure.

NL = YD − C − I

These things are not as straightforward as they look. Here’s an example. I can be both a saver and borrower.

Let’s say, I start with no assets/liabilities, earn $1mn in a year, pay taxes of $200,000, have consumption expenditure of $100,000 and buy a house worth $5m by borrowing $4.3m from a bank.

My saving is $700,000 and my net lending is minus $4.3 million [ = ($1mn − $200,000) − $300,000 − $5m].

Of course, the fact that I am a net borrower doesn’t make me poor. My house is worth $5m and I have a liability of $4.3m which implies my net worth is $700,000.

However, my liquidity is low. If tomorrow the economy collapses and I lose my job, I will be in a bad situation. In short, negative net lending (or a negative financial balance) of an economic unit or a sector contributes to financial fragility.

There’s another important point: even though I am a saver, my saving rate is 7/8, I have contributed hugely to aggregate demand. This can happen at a sectoral level as well. So perhaps this is the reason why Nick Rowe makes this distinction.

So if we were to blindly believe in Keynes, we would have concluded wrongly by just looking at the saving rate. But it is a matter of emphasis: economists make ceteris paribus arguments and I do not think Keynes didn’t understand this. He was perhaps holding everything else constant and changing the propensity to consume to highlight an important fact. But in real life ceteris is never paribus. What Keynes was arguing was that saving is not necessarily a good thing at the macro level.

Back to sectoral balances. Since, a sector’s (such as the household sector’s) negative net lending (or negative financial balance) adds to its financial fragility, this process will reverse. Private expenditure relative to private disposable income will fall. But this has an effect of being a drain on aggregate demand. And this can cause a recession.

Nick Rowe would have argued that it is the demand for money which caused a recession. Till here, it’s the same as argued above, because private expenditure falling relative to income is due to economic units trying to increase their liquidity. (There’s a “paradox” here: all units trying to reduce their fragility causes more fragility!).

There is however a difference: a sector’s or economic units’ demand for “money” can also be independent to income/expenditure and is more related to asset allocation between various kinds of financial assets. But here it cannot be said to cause a fall in aggregate demand and output. So a higher demand for money per se cannot be said to cause a recession.

As I was finishing writing this, JKH put up a comment at Nick’s blog saying Keynes understood it. I reproduce the comment below.

JKH:

There’s no question that Keynes appreciated the distinction between thrift and hoarding:

GT Chapter 9

“The rise in the rate of interest might induce us to save more, if our incomes were unchanged. But if the higher rate of interest retards investment, our incomes will not, and cannot, be unchanged. They must necessarily fall, until the declining capacity to save has sufficiently offset the stimulus to save given by the higher rate of interest. The more virtuous we are, the more determinedly thrifty, the more obstinately orthodox in our national and personal finance, the more our incomes will have to fall when interest rises relatively to the marginal efficiency of capital. Obstinacy can bring only a penalty and no reward. For the result is inevitable.”

GT Chapter 13

“The concept of hoarding may be regarded as a first approximation to the concept of liquidity-preference. Indeed if we were to substitute ‘propensity to hoard’ for ‘hoarding’, it would come to substantially the same thing. But if we mean by ‘hoarding’ an actual increase in cash-holding, it is an incomplete idea — and seriously misleading if it causes us to think of ‘hoarding’ and ‘not-hoarding’ as simple alternatives. For the decision to hoard is not taken absolutely or without regard to the advantages offered for parting with liquidity; — it results from a balancing of advantages, and we have, therefore, to know what lies in the other scale. Moreover it is impossible for the actual amount of hoarding to change as a result of decisions on the part of the public, so long as we mean by ‘hoarding’ the actual holding of cash. For the amount of hoarding must be equal to the quantity of money (or — on some definitions — to the quantity of money minus what is required to satisfy the transactions-motive); and the quantity of money is not determined by the public. All that the propensity of the public towards hoarding can achieve is to determine the rate of interest at which the aggregate desire to hoard becomes equal to the available cash. The habit of overlooking the relation of the rate of interest to hoarding may be a part of the explanation why interest has been usually regarded as the reward of not-spending, whereas in fact it is the reward of not-hoarding.”

Being the supreme macro-accountant (the first one really), he would be totally in tune with the general stock/flow consistency theme of the post-Keynesians.

Hoarding is a stock/asset allocation of liquidity, interconnected with the determination of the interest rate, as he notes above. He correctly rejected the idea of the interest rate as being determined by an “equilibrium” of saving and investment. He maintained correctly that those two measures are continuously equivalent.

Recession dynamics are a flow phenomenon as he describes it, using reconciliation of income accounting at two different points in time.

The behavior of liquidity, hoarding, and the interest rate is stock behavior (including hoarding) within that saving flow dynamic (including thrift).