I am not. But the post is about the possibility. The title is borrowed from a paper by Gérard Duménil and Dominique Lévy.

Steve Roth has an article titled Note To Economists: Saving Doesn’t Create Savings. If you follow his blog regularly, his pieces read

The definition of saving is wrong. Saving is equal to income minus expenditure.

That’s not an exaggeration. He actually says it:

… Since saving = income – expenditures, [aggregate] saving must equal zero.

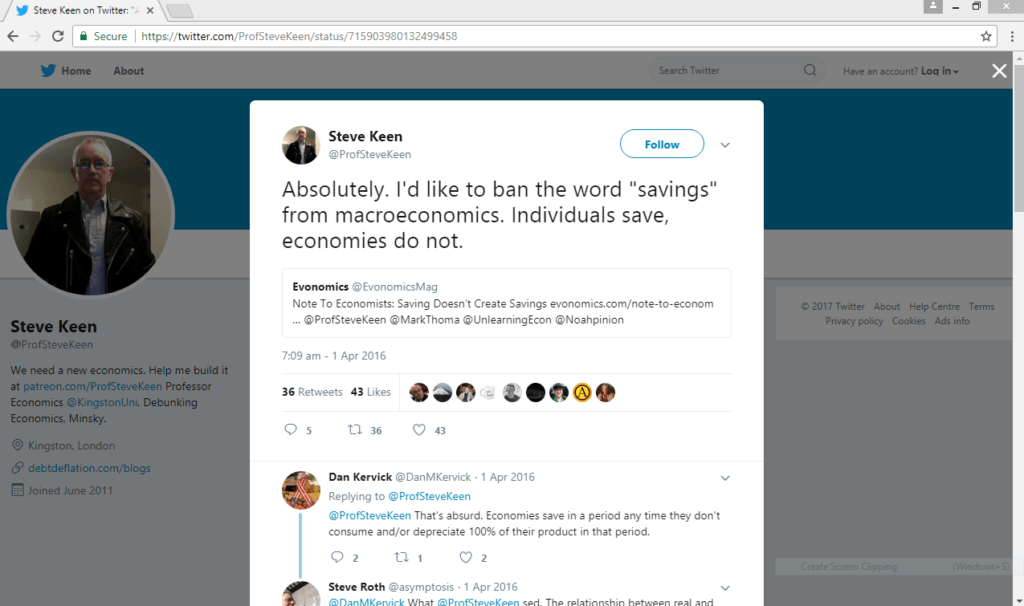

Steve Keen on Twitter supports Steve Roth.

click to view the tweet on Twitter

What’s with economists’ dislike for national accounts?

Steve Roth uses the phrase “savings” as a stock. Obviously his claim is just wrong as we know from national accounts:

Change in net worth = Saving + Holding Gains.

(with netting in holding gains).

Steve Keen doesn’t use saving as a stock but as a flow and a plural of saving. But Steve Keen’s point is also wrong. National saving is equal to the sum of saving of all economic units, such as households, firms, government etc. Even the household sector’s propensity to save collectively matters. That’s what macroeconomics is all about.

Now moving the more important point: is it possible that a higher propensity to consume reduces the long run rate of accumulation?

There are several Post-Keynesian economists who have considered the possibility. Of course it should be contrasted with supply side neoclassical economics. A few are Basil Moore, Wynne Godley, Marc Lavoie, and Gérard Duménil and Dominique Lévy as mentioned at the beginning of this post.

In their paper Kaleckian Models of Growth in a Coherent Stock-Flow Monetary Framework: A Kaldorian View, Godley and Lavoie find this in their models (draft version here):

We quickly discovered that the model could be run on the basis of two stable regimes. In the first regime, the investment function reacts less to a change in the valuation ratio-Tobin’s q ratio-than it does to a change in the rate of utilization. In the second regime, the coefficient of the q ratio in the investment function is larger than that of the rate of utilization (γ3 > γ4). The two regimes yield a large number of identical results, but when these results differ, the results of the first regime seem more intuitively acceptable than those of the second regime. For this reason, we shall call the first regime a normal regime, whereas the second regime will be known as the puzzling regime. The first regime also seems to be more in line with the empirical results of Ndikumana (1999) and Semmler and Franke (1996), who find very small values for the coefficient of the q ratio in their investment functions, that is, their empirical results are more in line with the investment coefficients underlying the normal regime.

… In the puzzling regime, the paradox of savings does not hold. The faster rate of accumulation initially encountered is followed by a floundering rate, due to the strong negative effect of the falling q ratio on the investment function. The turnaround in the investment sector also leads to a turnaround in the rate of utilization of capacity. All of this leads to a new steady-state rate of accumulation, which is lower than the rate existing just before the propensity to consume was increased. Thus, in the puzzling regime, although the economy follows Keynesian or Kaleckian behavior in the short-period, long-period results are in line with those obtained in classical models or in neoclassical models of endogenous growth: the higher propensity to consume is associated with a slower rate of accumulation in the steady state. In the puzzling regime, by refusing to save, households have the ability over the long period to undo the short-period investment decisions of entrepreneurs (Moore, 1973). On the basis of the puzzling regime, it would thus be right to say, as Dumenil and Levy (1999) claim, that one can be a Keynesian in the short period, but that one must hold classical views in the long period.

So there is a possibility that a higher propensity to consume leads to a lower growth in the long run. I do not think this is generally true, but this could be possible in some economies.

Two conclusions. It’s counter-productive to mix the definition of saving and what’s called “net lending” in national accounts. It’s possible (which shouldn’t mean that it’s necessarily the case) that Keynes’ paradox of savings doesn’t hold in the long run. I don’t believe that’s the case but purely arguing using national accounts and/or changing definitions won’t do.