The effort to understand the universe is one of the very few things which lifts human life a little above the level of farce and gives it some of the grace of tragedy.

– Steven Weinberg in The First Three Minutes.

Yearly Archives: 2016

Neochartalism, Balance Of Payments And Mainstream Economics

There have been many critiques of Neochartalism. Almost all of them, simply ignore the most important issue which makes Neochartalism the so-called “Modern Monetary Theory”, a chimera. A delusion.

Bill Mitchell has written a post on his blog about the balance-of-payments constraint, which among other things makes fun of physical appearance of Nicholas Kaldor. In that he correctly recognizes Nicholas Kaldor as the main proponent of this idea. Mitchell rightly represents Kaldor’s views:

In fact, Kaldor thought that exports were the only true ‘exogenous’ source of income growth, given that household consumption and business investment are considered to be ‘endogenously’ driven by fluctuations in (national) income itself.

In the post, Bill Mitchell doesn’t offer any argument as to why the literature behind it is supposedly wrong. He quotes Australia’s example but doesn’t recognize that Australia’s growth rate fits Thirlwall’s law. Had Australia grown much faster, its international indebtedness would grow to a much bigger size than now, which means its growth is limited by the balance of payments constraint.

Instead, Mitchell’s main point is:

While Thirlwall adopted a Keynesian position, the ‘balance of payments constraint’ he defined has underpinned the obsession with export-led growth strategies. It is a case where the IMF and others have co-opted the ‘Keynesian’ literature to impose neo-liberal solutions on nations.

In part, this is because ‘Keynesian’ literature was flawed.

Supposedly, its the Kaldorians who succumb into policies of the IMF because of their confusions! This is quite funny, given that Nicholas Kaldor was quite opposed to free trade which imposes a huge constraint on nation’s fortunes. In fact Kaldor and his colleagues at Cambridge were advocating import controls for Britain, which is obviously not a right-wing solution and was opposed by all.

One of my favourite articles is Foundations And Implications Of Free Trade Theory by Nicholas Kaldor, written in Unemployment In Western Countries – Proceedings Of A Conference Held By The International Economics Association At Bischenberg, France.

Nicholas Kaldor on free trade

Kaldor main point in the essay is a major opposite to the doctrine of free trade. Free trade is a policy of international organizations such as the IMF. So it’s not Nicholas Kaldor and others who are being fooled by the IMF, but Neochartalists themselves who think that if nations simply float their currencies, they get rid of their external constraint.

Here’s Kaldor:

Owing to increasing returns in processing activities (in manufactures) success breeds further success and failure begets more failure. Another Swedish economist, Gunnar Myrdal called this’the principle of circular and cumulative causation’.

It is as a result of this that free trade in the field of manfactured goods led to the concentration of manufacturing production in certain areas – to a ‘polarization process’ which inhibits the growth of such activitiesin some areas and concentrates them on others.

So as you see, there is an opposition to the “consensus” view. But according to Neochartalists, there is no problem with free trade: just expand domestic demand by fiscal policy. Imports are benefits, exports are costs according to them!

The main point of the post is that it is Neochartalists whose views are orthodox, not other Post-Keynesians following the work of Nicholas Kaldor. It’s funny of them to assert the other way. Look at it this way: opposition to free trade requires import controls, tariffs and things such as that. Is that the mainstream view – to put tariffs? However it is funny if you see a Neochartalist arguing against free trade as it would mean an inconsistency. If fiscal policy alone can bring full employment, why oppose free trade?

The Anwar Shaikh Lectures

y = x/π

‘The rate of growth (y) of any developed country in the long run is equal to the growth rate of the volume of its exports (x) divided by its income elasticity of demand for imports (π)’, he [Anthony Thirlwall] explained.

Our eyes were fixed on the blackboard, attempting to digest the meaning and internalize the implications of this tri-legged animal. That job was not easy. For the animal distilled volumes of legendary work in economic development, encapsulating all of them in a small-sized anti-underdevelopment pill. The teaching of Engel’s law, which implies that the demand for primary goods increases less than proportionally to increases in global income; the Harrod foreign trade multiplier which put forward the idea that the pace of industrial growth could be explained by the principle of the foreign trade multiplier; the Marshall– Lerner condition which implies that a currency devaluation would not be effective unless the devaluation-induced deterioration in the terms of trade is more than offset by the devaluation-induced reduction in the volume of imports and increase in volume of exports; the Hicks super-multiplier which implies that the growth rate of a country is fundamentally governed by the growth rate of its exports; the Prebisch–Singer hypothesis which asserts that a country’s international trade that depends on primary goods may inhibit rather than promote economic growth; the Verdoorn–Kaldorian notion that faster growth of output causes a faster growth of productivity, implying the existence of substantial economies of scale; Kaldor’s paradox which observed that countries that experienced the greatest decline in their price competitiveness in the post-war period experienced paradoxically an increase in their market share and not a decrease; the literature on export-led growth which asserts that export growth creates a virtuous circle through the link between output growth and productivity growth – all of these doctrines were somehow put into play and epitomized within this small-sized capsule. Not only that but the capsule was sealed by the novel and powerful ingredient of the balance-of-payments constraint: ‘in the long run, no country can grow faster than that rate consistent with balance of payments equilibrium on current account unless it can finance ever-growing deficits which, in general, it cannot’.

– Mohammed Nureldin Hussain, The Implications Of Thirlwall’s Law For Africa’s Development Challenges in Growth And Economic Development Essays In Honour Of A.P. Thirlwall, 2006

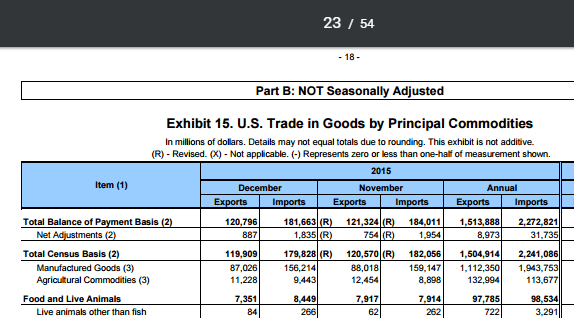

U.S. Manufacturing Deficit

The latest U.S. trade report is out and has data for the whole year 2015. Manufacturing deficit is something worth noting.

The U.S. manufacturing deficit is $831 bn.

U.S. Manufacturing Exports/Imports

It is sometimes said that manufacturing has lost its importance and that countries in balance of payments difficulties should look to trade in services to put things right. However, while it is still true that manufacturing output has declined substantially as a share of GDP, the figures quoted above show that the share of manufacturing imports has risen substantially. The importance of manufacturing does not reside in the quantity of domestic output and employment it generates, still less in any intrinsic superiority that production of goods has over provision of services; it resides, rather, in the potential that manufactures have for expansion in international trade.

– Wynne Godley, A Critical Imbalance In U.S. Trade, The U.S. Balance Of Payments, International Indebtedness, And Economic Policy, September 1995.

Kaldor’s Footnote And Kaldor On Sraffa

The world is more Kaldorian than Keynesian. After the crisis, Keynes became popular again but his Cambridge descendent Nicholas Kaldor is hardly remembered by the economics community. Even his biographers have some memory loss of him.

😉

Anthony Thirlwall and John E. King are biographers of Nicholas Kaldor. Superb books.

There’s a chapter Talking About Kaldor: An Interview With John King in Anthony Thirlwall’s book Essays on Keynesian and Kaldorian Economics. There’s an interesting discussion on money endogeneity (Google Books link):

J.E.K. … I wonder if Kaldor would have gone as far as Moore in arguing that the money supply curve is horizontal.

Anthony Thirlwall replies saying he would have argued that the supply of money is elastic with respect to demand, instead of quoting him. Here’s Nicholas Kaldor stating explicitly in a footnote in Keynesian Economics After Fifty Years, in the book, Keynes And The Modern World, ed. George David Norman Worswick and James Anthony Trevithick, Cambridge University Press, 1983, on page 36:

Diagrammatically, the difference in the presentation of the supply and demand for money, is that in the original version, (with M exogenous) the supply of money is represented by a vertical line, in the new version by a horizontal line, or a set of horizontal lines, representing different stances of monetary policy.

[italics: mine]

Anthony Thirlwall is one of the commenter in the book chapter. The book is proceedings of a conference on Keynes.

But that’s not enough. Turn to page 363 of the book.

A.P.T. He had a very high regard for Sraffa but he never wrote on this topic.

J.E.K. Not something that would really have concerned him very much? Too abstract and too removed from reality?

A.P.T. Probably, yes. It is quite interesting that Sraffa was his closest friend, both personal and intellectual, and they used to meet very regularly – almost every day when Sraffa was alive. But there’s no evidence that they ever discussed Production of Commodities by Means of Commodities.

J.E.K. That’s amazing. There’s certainly no evidence that he ever wrote anything on those questions.

A.P.T. There’s no evidence that he wrote anything, or that indeed he really understood Sraffa. Well, he had the broad thrust, but I don’t know that he ever read it carefully, or understood the implications.

In Volume 9, of Kaldor’s Collected Works, there are two memoirs. One of Piero Sraffa and the other on John von Neumann.

Nicholas Kaldor on Piero Sraffa

Interestingly the editors and F. Targetti (another biographer) and A.P. Thirlwall!

I guess if you know a person so closely – like the biographers do, of Kaldor- you tend to forget a few things about them.

Nick ROKE, Thrift, And Hoarding

The new issue of ROKE is out and celebrates 80 years of The General Theory. Nick Rowe has a new paper in the issue titled, Keynesian Parables Of Thrift And Hoarding. Requires access. Nick has a post on his blog where he welcomes comments.

Abstract:

I argue that Keynes missed seeing the importance of the distinction between saving in the form of money (‘hoarding’) and saving in all other forms (‘thrift’). It is excessive hoarding, not excessive thrift, that causes recessions and the failure of Say’s law. The same failure to distinguish hoarding from thrift continues from The General Theory into the IS–LM model and into New Keynesian macroeconomics. On this particular question, economists should follow Silvio Gesell rather than John Maynard Keynes. The rate of interest in New Keynesian models should be interpreted as a negative Gesellian tax (that is, a subsidy) on holding money issued by the central bank.

In my opinion, a part of it, the distinction between what’s called “hoarding” and “thrift” above is not something which Keynesians haven’t considered. In fact, in the sectoral balances approach, it is net lending and not saving whose behaviour is more highlighted.

A sector’s or an economic unit’s saving is defined as its disposable income less consumption expenditure.

S = YD − C

On the other hand, a sector’s net lending is defined as its disposable income less expenditure.

NL = YD − C − I

These things are not as straightforward as they look. Here’s an example. I can be both a saver and borrower.

Let’s say, I start with no assets/liabilities, earn $1mn in a year, pay taxes of $200,000, have consumption expenditure of $100,000 and buy a house worth $5m by borrowing $4.3m from a bank.

My saving is $700,000 and my net lending is minus $4.3 million [ = ($1mn − $200,000) − $300,000 − $5m].

Of course, the fact that I am a net borrower doesn’t make me poor. My house is worth $5m and I have a liability of $4.3m which implies my net worth is $700,000.

However, my liquidity is low. If tomorrow the economy collapses and I lose my job, I will be in a bad situation. In short, negative net lending (or a negative financial balance) of an economic unit or a sector contributes to financial fragility.

There’s another important point: even though I am a saver, my saving rate is 7/8, I have contributed hugely to aggregate demand. This can happen at a sectoral level as well. So perhaps this is the reason why Nick Rowe makes this distinction.

So if we were to blindly believe in Keynes, we would have concluded wrongly by just looking at the saving rate. But it is a matter of emphasis: economists make ceteris paribus arguments and I do not think Keynes didn’t understand this. He was perhaps holding everything else constant and changing the propensity to consume to highlight an important fact. But in real life ceteris is never paribus. What Keynes was arguing was that saving is not necessarily a good thing at the macro level.

Back to sectoral balances. Since, a sector’s (such as the household sector’s) negative net lending (or negative financial balance) adds to its financial fragility, this process will reverse. Private expenditure relative to private disposable income will fall. But this has an effect of being a drain on aggregate demand. And this can cause a recession.

Nick Rowe would have argued that it is the demand for money which caused a recession. Till here, it’s the same as argued above, because private expenditure falling relative to income is due to economic units trying to increase their liquidity. (There’s a “paradox” here: all units trying to reduce their fragility causes more fragility!).

There is however a difference: a sector’s or economic units’ demand for “money” can also be independent to income/expenditure and is more related to asset allocation between various kinds of financial assets. But here it cannot be said to cause a fall in aggregate demand and output. So a higher demand for money per se cannot be said to cause a recession.

As I was finishing writing this, JKH put up a comment at Nick’s blog saying Keynes understood it. I reproduce the comment below.

JKH:

There’s no question that Keynes appreciated the distinction between thrift and hoarding:

GT Chapter 9

“The rise in the rate of interest might induce us to save more, if our incomes were unchanged. But if the higher rate of interest retards investment, our incomes will not, and cannot, be unchanged. They must necessarily fall, until the declining capacity to save has sufficiently offset the stimulus to save given by the higher rate of interest. The more virtuous we are, the more determinedly thrifty, the more obstinately orthodox in our national and personal finance, the more our incomes will have to fall when interest rises relatively to the marginal efficiency of capital. Obstinacy can bring only a penalty and no reward. For the result is inevitable.”

GT Chapter 13

“The concept of hoarding may be regarded as a first approximation to the concept of liquidity-preference. Indeed if we were to substitute ‘propensity to hoard’ for ‘hoarding’, it would come to substantially the same thing. But if we mean by ‘hoarding’ an actual increase in cash-holding, it is an incomplete idea — and seriously misleading if it causes us to think of ‘hoarding’ and ‘not-hoarding’ as simple alternatives. For the decision to hoard is not taken absolutely or without regard to the advantages offered for parting with liquidity; — it results from a balancing of advantages, and we have, therefore, to know what lies in the other scale. Moreover it is impossible for the actual amount of hoarding to change as a result of decisions on the part of the public, so long as we mean by ‘hoarding’ the actual holding of cash. For the amount of hoarding must be equal to the quantity of money (or — on some definitions — to the quantity of money minus what is required to satisfy the transactions-motive); and the quantity of money is not determined by the public. All that the propensity of the public towards hoarding can achieve is to determine the rate of interest at which the aggregate desire to hoard becomes equal to the available cash. The habit of overlooking the relation of the rate of interest to hoarding may be a part of the explanation why interest has been usually regarded as the reward of not-spending, whereas in fact it is the reward of not-hoarding.”

Being the supreme macro-accountant (the first one really), he would be totally in tune with the general stock/flow consistency theme of the post-Keynesians.

Hoarding is a stock/asset allocation of liquidity, interconnected with the determination of the interest rate, as he notes above. He correctly rejected the idea of the interest rate as being determined by an “equilibrium” of saving and investment. He maintained correctly that those two measures are continuously equivalent.

Recession dynamics are a flow phenomenon as he describes it, using reconciliation of income accounting at two different points in time.

The behavior of liquidity, hoarding, and the interest rate is stock behavior (including hoarding) within that saving flow dynamic (including thrift).

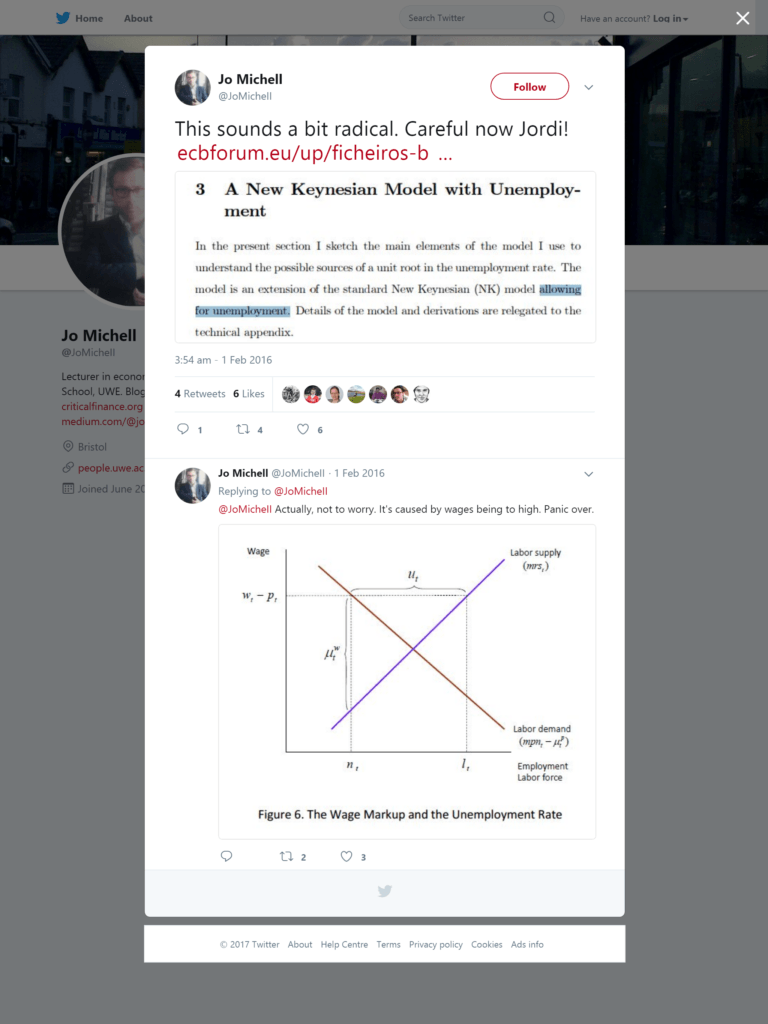

New Keynesian Economics Explained In Two Tweets

Kalecki And Keynes On Wages

The blogger writing for Social Democracy For The 21st Century: A Post Keynesian Perspective has an interesting post about Keynes’ view on wages.

I have a few points to add, which may not be contradictory to that post. It’s possible Keynes’ understanding changed from his discussions with Kalecki. In fact, Jan Toporowski, biographer of Michael Kalecki sees Kalecki’s position as far superior compared to that of Keynes. In an article titled Kalecki And Keynes On Wages, he says:

Both Kalecki and Keynes realised that their macroeconomic analysis depended critically on the inability of the labour market to be brought into equilibrium by changes in wages, as postulated by neoclassical theory. In 1939 therefore they wrote their explanation for this inability of free markets in capitalism to attain the equilibrium imagined by Robbins, in which all resources, including labour, are fully utilised. Keynes however got stuck on the effects of wages on the short-period equilibrium in an abstract Marshallian model. Kalecki was able to demonstrate more clearly the complex real income effects of wage changes.

…

Kalecki’s approach to the subject was much clearer, and free of Marshallian dilemmas applied to historical data.

Jan Toporowski, Levy Institute, May 2011

In the article, Toporowski points out the debate between Keynes and John T. Dunlop, Lorie Tarshis and Michal Kalecki. He also quotes Keynes from the GT:

in the short period, falling money wages and rising real wages are each, for independent reasons, likely to accompany decreasing employment; labour being readier to accept wage-cuts when employment is falling off, yet real wages inevitably rising in the same circumstances on account of the increasing marginal return to a given capital equipment when output is diminished.

Keynes was not fully correct on this but it is interesting to note that he was almost there. Perhaps his own quote explains: he himself couldn’t escape from old ideas which ramify into every corner of our minds.

In his book Post-Keynesian Economics: New Foundations, pp 277-278, Marc Lavoie says:

Indeed, in several versions of post-Keynesian short-run model of employment, higher real wages are conducive to higher levels of employment.

In their biography, Michal Kalecki (Great Thinkers In Economics), Julio López G and Michaël Assous point out that it was Michal Kalecki who first figured this out before Dunlop-Tarshis-Kalecki (1939) in his 1938 paper The determinants of distribution of the national income, also published in Collected works of Michal Kalecki, Vol. I, edited by J. Osiatynsky, Oxford University Press, 1990.

So here’s Kalecki. It’s great and humble of him to call it the “Keynesian theory”, although he found something contrary to Keynes’ own point. But that’s the thing about Keynes – he said a lot of things which is contrary to his own revolutionary thoughts. Heterodox economists see it in a nicer way. Joan Robinson would have said, “Keynes should not have said that”. Keynes’ opponents would pounce on his several vulnerabilities. And then there’s the bastardization of Keynes’ work. Most of economics before the crisis simply states: “Keynes is wrong”. Over to Kalecki:

Final remarks

1. There are certain ‘workers’ friends’ who try to persuade the working class to abandon the fight for wages in its own interest, of course. The usual argument used for this purpose is that the increase of wages causes unemployment, and is thus detrimental to the working class as a whole.

The Keynesian theory undermines the foundation of this argument. Our investigation above has shown that a wage increase may change employment in either direction, but that this change is unlikely to be important. A wage increase, however, affects to a certain extent the distribution of income: it tends to reduce the degree of monopoly and thus to raise real wages. On the other hand, ‘real’ capitalist incomes tend to fall off because of the relative shift of income from rentiers to corporations, which lowers capitalist propensity to consume.

If viewed from this standpoint, strikes must have the full sympathy of ‘workers’ friends’. For a rise in wages tends to reduce the degree of monopoly, and thus to bring our imperfect system nearer to the ideal or free competition. On the other hand, it tends to increase the thriftiness of capitalists by causing a relative shift of income from rentiers to corporations. And ‘workers’ friends’ are usually admirers both of free competition and or thrift as a virtue of the capitalist class.

2. Another question may arise in connection with the Keynesian theory of wages. Is not the struggle of workers for higher wages idle if they lose whatever gain they may make in the form of a higher cost of living? We have shown that wage reduction causes a change in the distribution of the national income to the disadvantage of workers, and that in the event of an increase in wages the reverse occurs. This is not to deny, however, that changes in real wages are much smaller than those in money wages; but never the less they may be quite material, especially as we are dealing with averages which reflect only slightly great fluctuations in real wages in particular industries.

We noticed above the great stability of the relative share of manual labour in the national income. This is not in contradiction with the influence of money wages upon the distribution of the national income. On the contrary, the resistance to wage cuts prevents the degree of monopoly from rising in the slump to the extent it would if ‘free competition’ prevailed on the labour market. Although, in fact, the relative share of manual labour is more or less stable, this would not obtain if wages were very elastic.

It is quite true that the fight for wages is not likely to bring about fundamental changes in the distribution of the national income. Income and capital taxation are much more potent weapons to achieve this aim, for these taxes (as opposed to commodity taxes) do not affect prime costs, and thus do not tend to raise prices. But in order to redistribute income in this way, the government must have both the will and the power to carry it out, and this is unlikely in a capitalist system.

I came across the UN Global Policy Model document with lots of equations and written by Francis Cripps and Alex Izurieta. (h/t Jo Michell). The article date is May 2014.

Just thought I should link it for readers interested.

(The post title is the link).