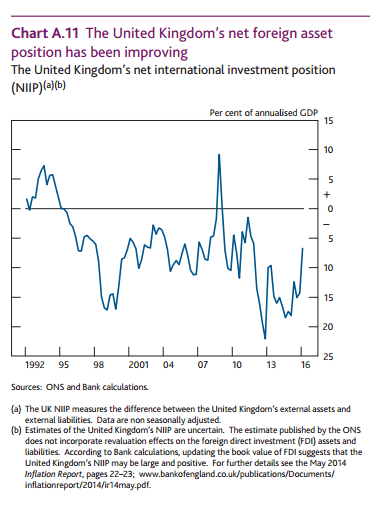

Trade has always been a subject close to non-orthodox economics. Post-Keynesians emphasize the principle of circular and cumulative causation, which in the words of Nicholas Kaldor means, “success creates further success and failure begets more failure”. The importance of trade for the prospects of the US economy was emphasized the most by Wynne Godley in his series of papers for the Levy Institute from the mid-90s to late 2000s. In his paper Seven Unsustainable Processes, Godley said,

The logic of this analysis is that, over the coming five to ten years, it will be necessary not only to bring about a substantial relaxation in the fiscal stance but also to ensure, by one means or another, that there is a structural improvement in the United States’s balance of payments. It is not legitimate to assume that the external deficit will at some stage automatically correct itself; too many countries in the past have found themselves trapped by exploding overseas indebtedness that had eventually to be corrected by force majeure for this to be tenable.

There are, in principle, four ways in which the net export demand can be increased: (1) by depreciating the currency, (2) by deflating the economy to the point at which imports are reduced to the level of exports, (3) by getting other countries to expand their economies by fiscal or other means, and (4) by adopting “Article 12 control” of imports, so called after Article 12 of the GATT (General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade), which was creatively adjusted when the World Trade Organization came into existence specifically to allow nondiscriminatory import controls to protect a country’s foreign exchange reserves. This list of remedies for the external deficit does not include protection as commonly understood, namely, the selective use of tariffs or other discriminatory measures to assist particular industries and firms that are suffering from relative decline. This kind of protectionism is not included because, apart from other fundamental objections, it would not do the trick. Of the four alternatives, we rule out the second–progressive deflation and resulting high unemployment–on moral grounds. Serious difficulties attend the adoption of any of the remaining three remedies, but none of them can be ruled out categorically.

In his 2008 paper, Prospects For The United States And The Rest Of The World: A Crisis That Conventional Remedies Cannot Resolve, he said:

At the moment, the recovery plans under consideration by the United States and many other countries seem to be concentrated on the possibility of using expansionary fiscal and monetary policies.

But, however well coordinated, this approach will not be sufficient.

What must come to pass, perhaps obviously, is a worldwide recovery of output, combined with sustainable balances in international trade. Since this series of reports began in 1999, we have emphasized that, in the United States, sustained growth with full employment would eventually require both fiscal expansion and a rapid acceleration in net export demand. Part of the needed fiscal stimulus has already occurred, and much more (it seems) is immediately in prospect. But the U.S. balance of payments languishes, and a substantial and spontaneous recovery is now highly unlikely in view of the developing severe downturn in world trade and output. Nine years ago, it seemed possible that a dollar devaluation of 25 percent would do the trick. But a significantly larger adjustment is needed now. By our reckoning (which is put forward with great diffidence), if the United States were to attempt to restore full employment by fiscal and monetary means alone, the balance of payments deficit would rise over the next, say, three to four years, to 6 percent of GDP or more—that is, to a level that could not possibly be sustained for a long period, let alone indefinitely. Yet, for trade to begin expanding sufficiently would require exports to grow faster than we are at present expecting, implying that in three to four years the level of exports would be 25 percent higher than it would have been with no adjustments.

It is inconceivable that such a large rebalancing could occur without a drastic change in the institutions responsible for running the world economy—a change that would involve placing far less than total reliance on market forces.

So there was a voice for the Post-Keynesian community talking about US trade.

Dean Baker has an article saying the TPP gave us Trump and I agree. Although Donald Trump is a disaster socially, he is less dogmatic about trade and has promised to put tariffs on China (and has even promised fiscal expansion!). Since the Democrats (except Bernie Sanders) didn’t say anything about it and guarded orthodoxies, I believe this was decisive for Trump’s victory.

For the sake of quotes, here’s from The New York Times, July 31, 2016:

Mr. Trump himself said in a telephone interview last week that he believed more borrowing and spending would help lift economic growth, a departure from traditional Republican economics.

“It’s called priming the pump,” Mr. Trump said. “Sometimes you have to do that a little bit to get things going. We have no choice — otherwise, we are going to die on the vine.”

He added: “The economy would be crushed under Hillary. But no matter who it is, the debt is going up.”

Here’s a fun video of Donald Trump saying China in loop

click the picture to see the video on YouTube.

Since today morning the BBC has been saying how immoral Trump’s policies are: that fiscal expansion invariably burdens future generations and that thinking of the Chinese government using unfair trade policies is orthodoxy.

That’s not all, Paul Krugman even claimed that equity prices aren’t going to ever rise to pre-Trump level, a position which he flipped within hours after financial markets recovered.

So it’s not difficult to conclude that purely for the sake of defending one’s favourite party or ideology, people are going to make the case against fiscal policy and for free trade. We might hear a lot of pre-Keynesian orthodoxies from smart people more and more. I won’t even be surprised if Paul Krugman becomes a fiscal hawk again.

This has already been the case in discussions around wars. George Bush started the Iraq war and faced a lot of opposition from the so-called progressives. But then Barack Obama is the record holder for the most number of days as being in office as the President of the United States while the nation was at war but hardly gets any opposition from those who opposed him. I have also noticed that the same people who opposed Bush are now war apologizers.

So economic orthodoxy lies ahead. What will be sad is that it will come from people to the left of Republicans in the political spectrum.