The Kaldor-Verdoorn Law conjectures that the causality is mainly from GDP to productivity. It’s not obvious to most economists. They do observe that GDP rises fast when productivity is rising fast but don’t see the direction of causality and assume it’s from the latter to the former. Some do see some connection, such as Lawrence Summers who talks of the damage to the supply side because of the economic crisis. However they are thinking of it as an exception than a general rule.

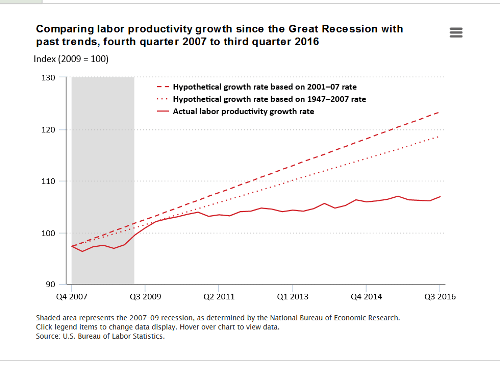

I came across this chart from the U.S. Bureau of Labour Statistics showing how productivity growth has suffered.

A recent example of someone failing to see the casuality is Jon Cunliffe, the Deputy Governor for Financial Stability, Bank of England. In a recent speech he said:

Productivity has been disappointing since the financial crisis. … Weak productivity growth has almost certainly been one of the main reasons for the weak growth in pay we have seen in the UK since the crisis. Over the last decade real earnings have grown at the slowest rate since the mid-19th century

Cunliffe fails to recognize that the slow growth is mainly due to the tight fiscal stance of the U.K. government. Had it relaxed fiscal policy, growth in GDP would have been higher, and productivity would have also risen and so would have pay, since productivity rise can be said to be one of the causes for wage rises. In other words, he is thinking of productivity rise as exogenous when pinpointing the blame of weak pay rise.

Still, productivity rise is important. Although production rise is demand-led, if productivity doesn’t rise or doesn’t rise fast enough, output is more constrained. Large rises in productivity would imply that output has more scope to be expanded. So we have path dependency and super-hysteresis.