Recently Paul Krugman wrote up an article, Globalization: What Did We Miss? for the IMF globalisation conference last fall. The paper is a large concession to the points some economists have been making on international trade and globalisation. Krugman concedes that:

soaring imports did impose a significant shock on some U.S. workers, which may have helped cause the globalization backlash.

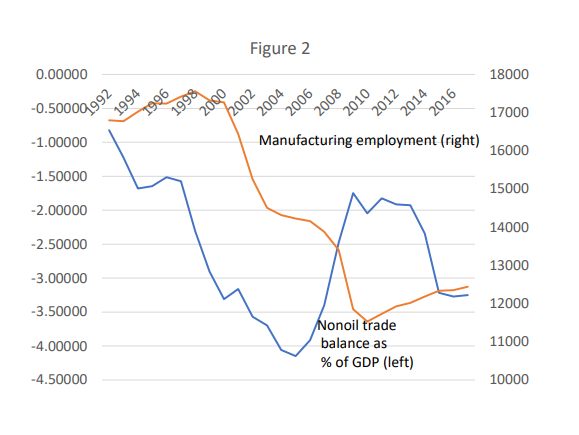

He also draws this chart, coming to the view that the US trade has led to a weakness of manufacturing.

The New Consensus narrative is that loss of employment is due to productivity rises and not due to international trade. Now Krugman has accepted the view that it is the latter.

Further, he also says:

Until the late 1990s employment in manufacturing, although steadily falling as a share of total employment, had remained more or less flat in absolute terms. But manufacturing employment fell off a cliff after 1997, and this decline corresponded to a sharp increase in the nonoil deficit, of around 2.5 percent of GDP.

Does the surge in the trade deficit explain the fall in employment? Yes, to a significant extent. A trade deficit doesn’t produce a one-for-one decline in manufacturing value added, since a significant share of both exports and imports of goods include embodied services. But a reasonable estimate is that the deficit surge reduced the share of manufacturing in GDP by around 1.5 percentage points, or more than 10 percent, which means that it explains more than half of the roughly 20 percent decline in manufacturing employment between 1997 and 2005.

Again, this is over a relatively short time period and focuses on absolute employment, not the employment share. Trade deficits explain only a small part of the long-term shift toward a service economy. But soaring imports did impose a significant shock on some U.S. workers, which may have helped cause the globalization backlash.

And trade deficits are, as I said, part of a broader story of adjustment issues.

Manufacturing is important partly because of increasing returns to scale and partly because it’s easier to export manufactures, although services are catching up.

Further, he quotes the work of Autor, et. al.:

This is where the now-famous analysis of the “China shock” by Autor, Dorn, and Hanson (2013) comes in. What ADH mainly did was to shift focus from broad questions of income distribution to the effects of rapid import growth on local labor markets, showing that these effects were large and persistent. This represented a new and important insight.

To make partial excuses for those of us who failed to consider these issues 25 years ago, at the time we had no way of knowing that either the hyperglobalization shown in Figure 1 or the trade deficit surge shown in Figure 2 were going to happen. And without the combination of these developments the “China shock” would have been much smaller. Still, we missed an important part of the story.

But concessions of previous held orthodox views are hardly straightforward. Despite this large concession, Krugman still wants to defend free trade and is against any tariffs. One may critique selective protectionism but there is also the option of imposing tariffs non-discriminately, i.e., non-selective protectionism.

More importantly, as Joan Robinson often stressed the thesis of free trade ought to also come with the answer to the question: what is the mechanism for resolving imbalances? Free traders always avoid this question, sometimes claiming—as Milton Friedman did—that floating exchange rates does the trick. But we know that it’s hardly the case. In the absence of any market mechanism, we need an official mechanism.