Jason Hickel is a great economist and today I was looking up his 2018 book The Divide.

I found a nice passage:

The stated goal of the World Trade Organization is to create a ‘level playing field’ among trading partners. Each member has to play by the same rules — the same low tariffs and the same ban on subsidies. But in reality the idea of a level playing field is something of an illusion. when rich countries step onto the playing field they do so with industries that are immensely powerful and competitive — precisely because they spent their formative years of development under heavy protection. Poor countries, for their part, step onto the playing field with industries that have never had the benefit of protection and therefore have no hope of competing with their counterparts in rich countries. It may be a level playing field, but what good is a level playing field in a match between schoolchildren and a Premier League team? The rules are the same for both sides, but that doesn’t mean the game is equitable …

…

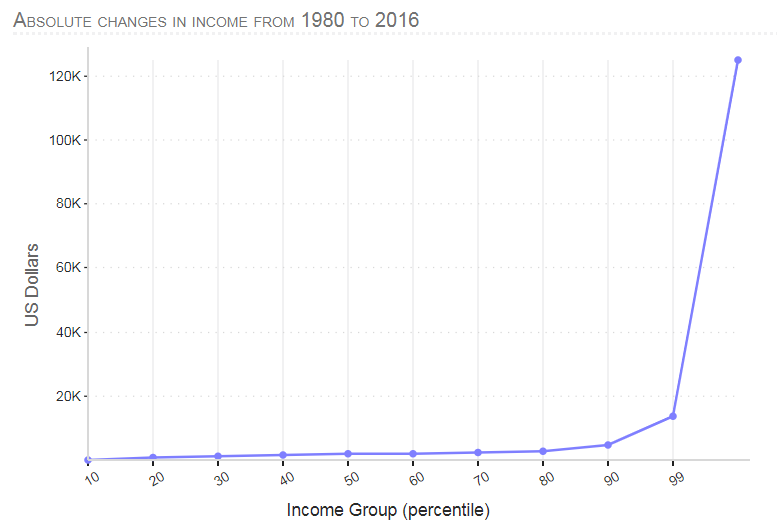

Even if we assume that the game is in fact equitable, if we look more closely it becomes clear that the ‘level playing field’ is actually not very level at all: the rules are unfair even by the WTO’s own standards. Theoretically, the WTO requires every country to reduce their tariffs and subsidies to the same level, but in reality these cuts are applied selectively in favour of rich countries.

In the book Hickel attempts to prove among many things that:

Poor countries are poor because they are integrated into the global economic system on unequal terms.