This is in continuation of the post Neochartalists (“MMTers”) On Turkey, written three days ago and which didn’t discuss what neochartalists (“MMT” people) have to say about the crisis. I am looking specifically a blog post Turkey Tells Us Nothing About MMT – But MMT Tells Us A Lot About Why Turkey Is In Trouble by Bill Mitchell written yesterday.

Bill Mitchell is responding to critics and he describes their criticisms as follows:

I have noticed a lot of Internet traffic about Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and the situation in Turkey at present. Apparently, as the narrative goes, MMT is finally being revealed as a fraud because Turkey’s economy is going backwards and its currency is depreciating rapidly. The logic, it seems, is that if a nation enters rough economic waters and the financial markets sell its currency (although remember someone has to be buying it simultaneously) then that proves MMT is false. An extraordinarily naive viewpoint if you think about it.

As if someone having to be buying it simultaneously is some kind of owning of critics!

Anyways, Mitchell straightforwardly denies there’s some issue with neochartalism in the conclusion:

What is clear, an MMT understanding leads one to worry intensely about a nation that has built a growth strategy on vast amounts of foreign currency debt and expanding exports. The two arms of this sort of growth strategy leaves a nation highly vulnerable to changes of circumstances in world export markets.

Add in a central bank that is also borrowing foreign currencies and showing it intends to use their stores to defend the lira.

Add in a deregulated banking sector that is flooded with foreign debt to maintain profits.

Result: disaster pending.

So at least he accepts there’s a crisis rather than dismissing the whole thing as meh!

I don’t think his point about over-reliance on exports is correct but his main points is the holding of foreign currency debt by the government (or the central bank).

The important point however is that an external crisis will always go through a phase where the government has negative open positions in foreign currency. Neochartalists can always claim that neochartalism is right but that’s useless to anyone. Neochartalists fail to understand why such a thing happens from a monetary theory/finance perspective.

The idea that some governments have to necessarily issue debt in foreign currency comes as counterintuitive but the alternative is shutting down of the foreign exchange markets and economic activity with the rest of the world. When the exchange rate is falling, the government must sell foreign exchange to stabilise. Like buying foreign exchange has an depreciating effect on the currency, selling has the reverse. The sale of foreign exchange shifts foreigners’ portfolio from assets held in the domestic currency to assets held in foreign currency, bringing about a reduction in order flows to sell. But the amount of foreign exchange to be sold can be large. And the above illustrates how governments/central banks would need to obtain foreign currency to sell and in the process become indebted in foreign currency. It’s as simple as that!

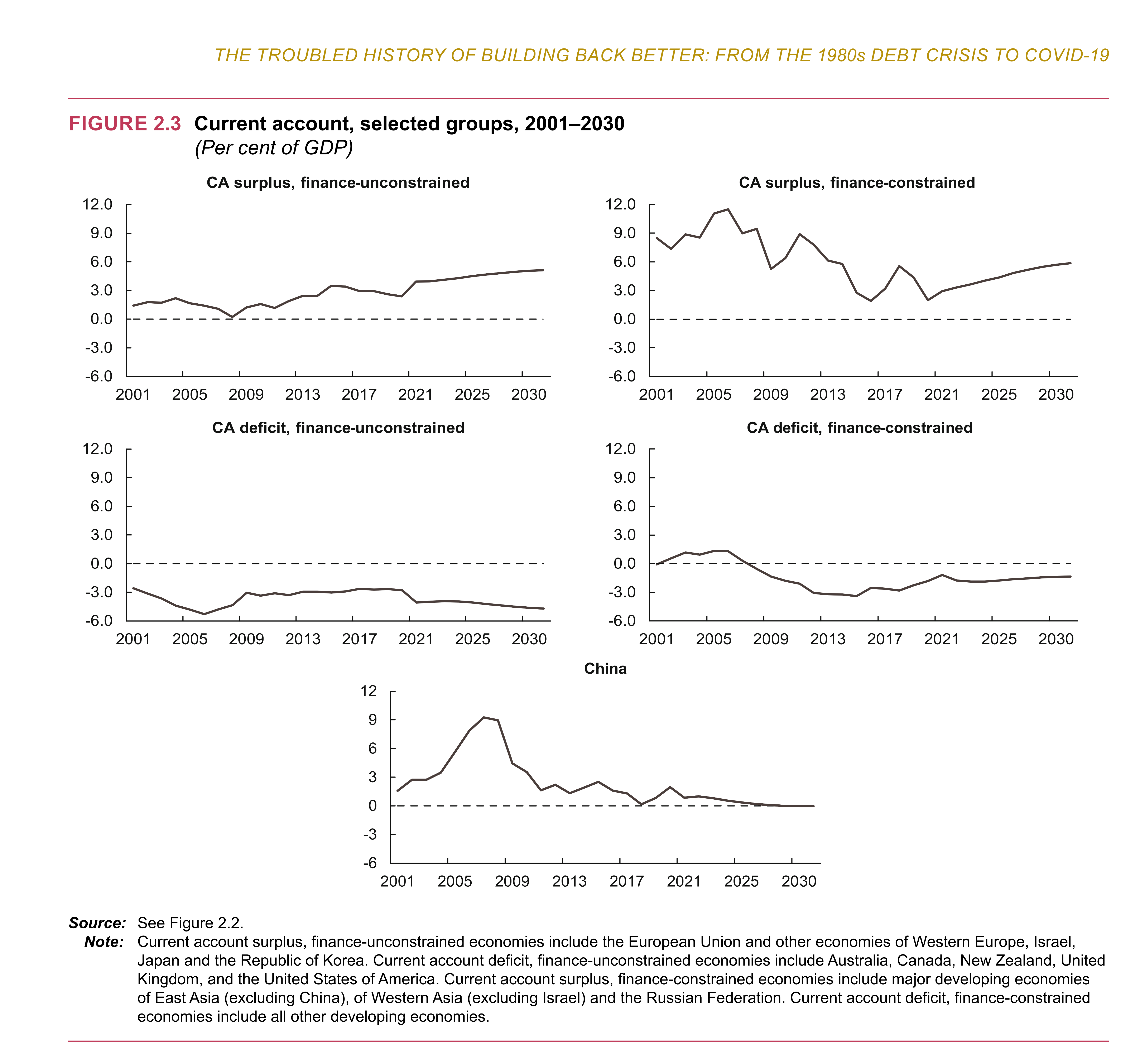

Of course the government/central bank can also obtain foreign exchange from purchases in the foreign exchange markets, when exports are high compared to imports, and build reserves this way without affecting the exchange rate too much and many countries’ governments do that, but it’s not always possible as exports depends on competitiveness in world markets and general demand conditions.

Ronald McKinnon—although a neoclassical economist—understood this problem and had a fine description of problems governments face because of the foreign exchange market in his paper Money And Finance On The Periphery Of The International Dollar Standard, published in 2002. See Section 6 on various options available via fixing or floating exchange rates and banking/finance regulation and limitations. You need to filter out the wrong stuff to extract the good parts!

So blaming the government for having government debt in foreign currency isn’t helpful. It’s just like neoclassical economics: the theory goes wrong, blame the actors instead of wondering if your theory might be wrong.