A good macroeconomic model would use national accounts and the flow of funds with behavioural hypotheses. It’s complicated by the fact that prices of goods and services change. It’s not just that if prices of goods and services change, you’re consumption would change in response to that, but also because say the deposits you hold in the bank is worth less.

So your behavioural equations need to be modified. It’s not easy. Wynne Godley recalls in his book Monetary Economics:

And no lesser authority than Richard Stone (1973) made the same mistake because in his definition of real income he did not deduct the erosion, due to inflation, of the real value of household wealth.

…

References

…

Stone, R. (1973) ‘Personal spending and saving in post war Britain’ in H.C. Bos, H. Linneman and P. de Wolff (eds), Economic Structure and Development: Essays in Honour of Jan Tinbergen (Amsterdam: North Holland), pp. 75–98.

The system of national accounts does recognise the importance of this but there aren’t any real variables defined. Real as opposed to nominal. Instead holding gains (formal phrase for “capital gains”) is divided into two parts: real holding gains and neutral holding gains. So,

Nominal holding gains = real holding gains + neutral holding gains.

Assets prices can rise differently than prices of goods and services. Para 12.89 says:

The real holding gain on an asset is defined as the difference between the nominal and the neutral holding gain on that asset. The values of the real holding gains on assets thus depend on the movements of their prices over the period in question, relative to movements of other prices, on average, as measured by the general price index. An increase in the relative price of an asset leads to a positive real holding gain and a decrease in the relative price of an asset leads to a negative real gain, whether the general price level is rising, falling or stationary.

Of course we should consider holding gains and losses on liabilities as well.

This is anyway complicated practically. I haven’t yet seen national accounts of any country producing such tables. But the SNA—including the 2008 SNA—doesn’t have any framework beyond this. This is because it considers that economic behaviour would be different for real holding gains or losses, as opposed to just the flow aspect.

In other words, if your (nominal) income is $100 and there’s a 10% inflation, your consumption would fall. But you might not react the same if you have a real holding loss of $10.

But to a first approximation you could simplify and bring real holding gains into real income. I have simplified quite a bit and these are quite challenging things, so I refer you to Wynne Godley and Marc Lavoie’s (G&L)’s book Monetary Economics.

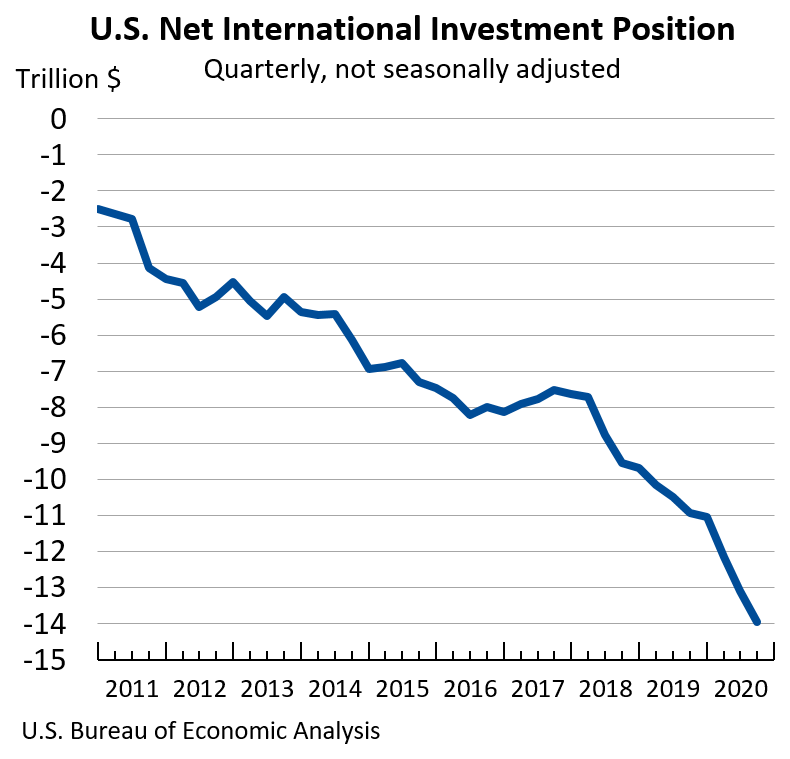

I wrote this post after an online discussion about the government “inflating away the nominal debt”. Although such claims are loaded, there is some logic to it. In inflation accounting, holding gains/losses appear in incomes. Modeling involves going back and forth between real and nominal variables.

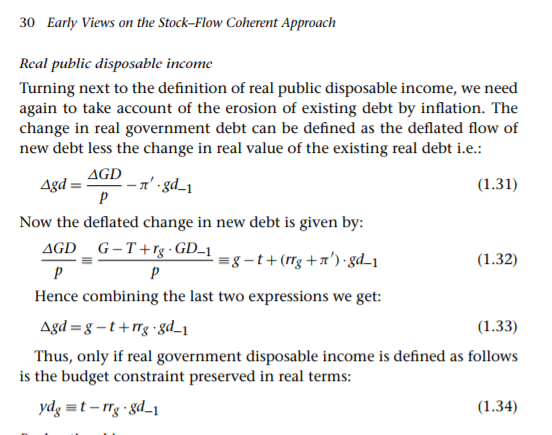

An original writing is that of Wynne Godley (and Ken Coutts and Graham Gudgin)—a 1985 paper titled Inflation Accounting Of Whole Economic Systems. In that you see the equation:

(Snipped from the 2012 reprint).

So the government disposable income (in addition to taxes and central bank profits, also has the holding losses due to the fact that prices of goods and services has increased in the period, not just because of changes in prices of government bonds).

Of course, there’s also the loadedness of the phrase “inflating away the debt”. That’s a different matter, my point here is to address the intuition of why inflation can be thought of as bringing revenue to the government and reducing its debt.