Two recent statistical releases which needs attention: the US international investment position and the primary income in the balance of payments turning negative.

Charts from the BEA:

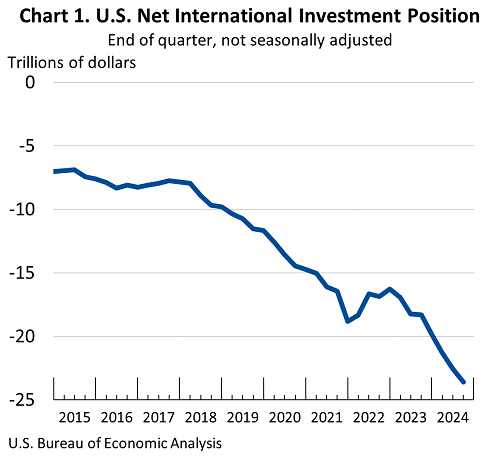

Source: U.S. International Investment Position, 3rd Quarter 2024

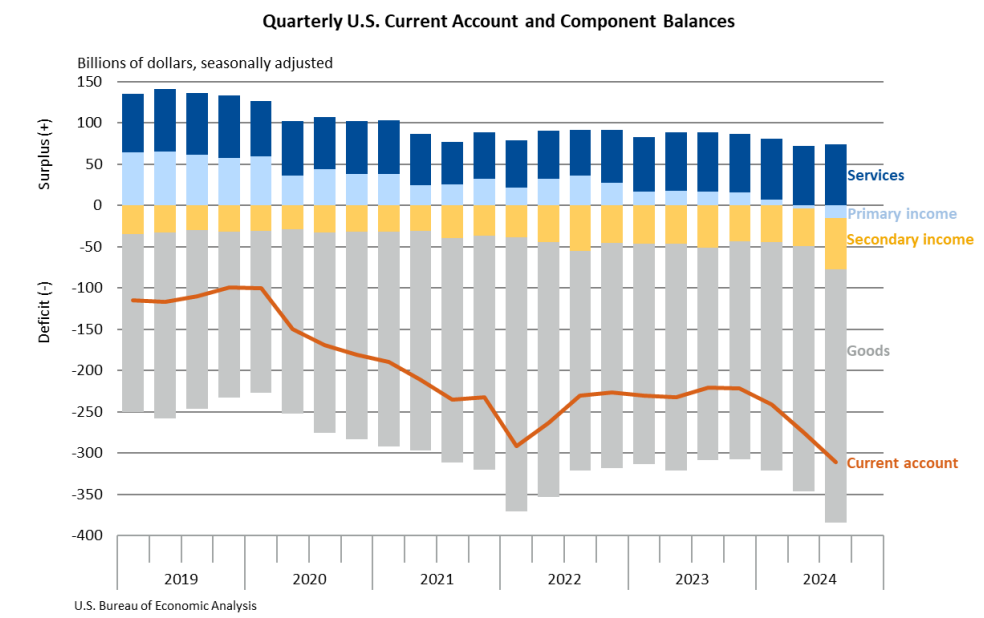

Source: U.S. Current-Account Deficit Widens in 3rd Quarter 2024

For an idea, the US GDP was $29.4 trillion in Q3 on an annualised basis, according to the Fed’s Z.1.

Now a lot has been written on this but I suppose rise of the US net indebtedness (the negative of the net international investment position) has been slower than anyone expected, including the great Wynne Godley. One of the reasons of course is that the primary income balance has been positive for long, which is surprising in a way. Primary income mainly consists of income from income from direct investment, dividends and interest income. Lots has been written on this too, and the connection between the two, but once the balance on primary income turns negative, the net indebtedness will rise at a faster rate.

Now, even though a lots has been written on this, mainstream economists have shooed measures such as import controls and improvement of exports. The only exception among economists was Wynne Godley.

Some measures have been taken by the United States such as tariffs, industrial policy. These have been taken in limited ways as there is a lot of ideological opposition to such things. But obviously with China on the rise and its ever expanding rise in its current account balance in its balance of payments, there is some realisation that the United States needs to do something more. The rise in China also injures other countries, so the problem is becoming more international.

Generally economists make it look like international trade is a small complication in the economic theory, and lack understanding of how it is central to the way the world works. With rising imbalances—on the negative in the United States and the other way round in China, is not good for the world in another way because a slowdown of the United States to keep its finances in check slows the growth everywhere. So from the point of view of a poor country, say India, the need to address both US imbalance and the rise of China are highly important.