The Financial Times has a column titled Europe’s Fiscal Union Envy Is Misguided. The author echoes a recent article in The New York Times (referred here in my blog). According to the FT columnist, in the United States,

… The bulk of the risk-sharing happens through credit and capital markets – that is to say, private lending, borrowing and investment returns do most of the job of evening out regional shocks.

and,

… The best thing the eurozone can do to promote risk-sharing is to stop flirting with its own disintegration: as long as investors suspect politicians might let the currency unravel, they will hunker down behind national borders. Next, get cracking on developing the capital markets union – where there is much more reason to envy the Americans.

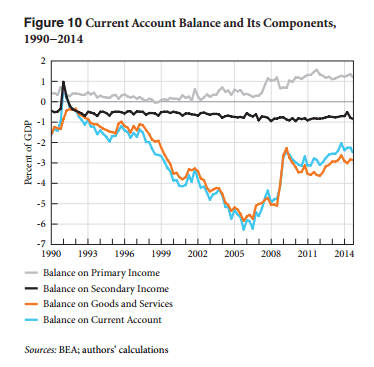

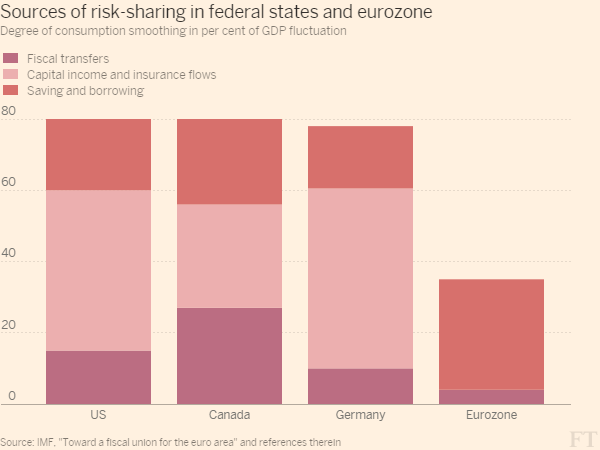

In addition, the FT author presents the following graph.

Let’s see how a federal system works.

There are regions with local governments but there is also a federal government which raises taxes from economic units of all regions and spends on the units. Some regions will be net recipients of such flows of funds — the government expenditure toward these regions is higher than what it receives in taxes — while others will pay more taxes than what they receive from the government. These needn’t sum to zero, as the federal government may be in a deficit.

There is one peculiar thing in the way such accounting is done. The federal government is outside all regions when studying balance of payments of each region. However for the whole group, the federal government is inside. The Sixth Edition of the IMF’s Balance Of Payments And International Investment Position Manual (BPM6) does this in a similar way for monetary unions, such as for the Euro Area. In that case, the European Central Bank and the European Parliament and other such supranational institutions are considered to be outside each nation when nations’ balance of payments statistics is produced, but inside when the balance of payments of the whole region is studied.

Now, some regions may see an improvement in their balance of payments compared to the case where there is no federal government. There are four kinds of flows which are important here when thinking about the current account balance of payments of a region:

- Exports

- Imports

- Federal government expenditures and transfers

- Federal taxes and transfers.

Of course, expenditure of the federal government in the region itself may be thought of as an export, so exports in the list above is meant to exclude that and include transactions such as a private sector producer selling a car to a household in another region.

So one can roughly identify surplus regions as ones which have higher exports than imports in the definition above and others as deficit regions. These transactions of course also affect the capital and financial accounts of the balance of payments and the “regional investment position”.

Usually, one thinks of “fiscal transfers” as affecting aggregate demand. But from the above analysis, it should be clear that it also affects the regional investment position. Economic units in deficit regions also see an improvement in their net asset position. Economic units in deficit regions in aggregate will typically receive more federal government payments than what they send in taxes. The counterpart to this in the capital and financial account of the balance of payments is an improvement in their net acquisition of financial assets and net incurrence of liabilities, as compared to the case where there is no federal government. This is turn improves the regional investment position.

Of course there is still a possibility that the private sector of a union with a federal government as a whole may turn unsustainable but at least there is a regional mechanism of improvement compared to the case when there is no federal government.

To summarize, the point of the above analysis is that the financial sector as a whole cannot achieve this on its own. It takes a federal government to not only affect demand in all regions but also keep their debts in check. The workings of finances of a federal government affects the asset and liability positions of any region as a whole. The financial sector cannot take up the task of a federal government.