Gerald Epstein of PERI has written a fine paper The Institutional, Empirical and Policy Limits of ‘Modern Money Theory’ critiquing the shortcoming of Neochartalism.

Epstein’s main critique is that Neochartalism ignores the role of international financial markets and the constraint it puts on fiscal policy. Abstract:

Modern Money Theory (MMT) economists acknowledge a number of empirical and institutional limitations on the applicability of MMT to macroeconomic policy, but they have not attempted to explore these empirically nor have they adequately addressed their implications for MMT’s main macroeconomic policy proposals. This paper identifies some of these important limitations, including those stemming from modern international financial markets, and argues that they are much more binding on the policy applicability of MMT than many of MMT’s advocates appear to recognize. To address these limitations, MMT analysts would have to enter the messy institutional, policy and empirical realms that undermine their simplistic policy conclusions that might be appealing to some policy-oriented followers of MMT. My conclusion is that, in light of these limitations, MMT’s major macroeconomic policy suggestions are of little practical relevance today for progressive politicians and activists, much less to macroeconomic policy formulation in general.

In addition, Epstein has a blog post, Is MMT “America First” Economics?, at INET, which is a short summary of his paper. Excerpt:

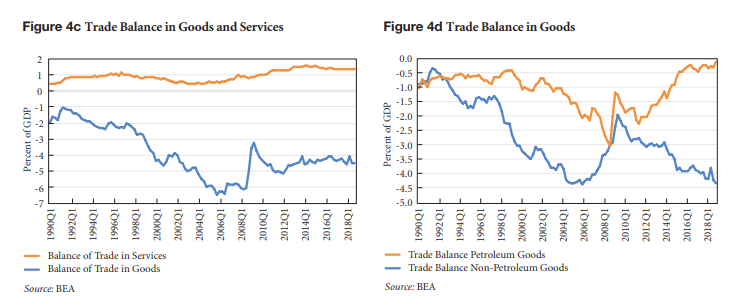

To start, even though MMT advocates claim that its macroeconomic framework applies to all countries with “sovereign currencies,” there is significant evidence that it does not apply to the vast majority of such countries in the developing world that are integrated into global financial markets. As is well-known, these countries are subject to the vagaries of international capital flows, sometimes called “sudden-stops.” The problem is that in light of these flows, these countries have limited fiscal and monetary policy space, surely insufficient to conduct MMT-prescribed monetary and fiscal policies for full employment. Wray argues that that flexible exchange rates are sufficient to provide sufficient policy space for these countries to undertake MMT macro-policies. Occasionally the issue of capital controls is briefly mentioned but not seriously discussed as a complementary policy. But a careful survey of the empirical evidence casts grave doubts on the effectiveness of flexible rates for giving policy autonomy or insulating these countries from the vagaries of global financial flows. This problem is worse for countries that cannot borrow in their own currencies, but also applies to small, open countries that are able to borrow in their own currencies. The upshot is that only countries that issue their own internationally accepted currency might have the policy space to conduct MMT policies.

Even for those countries that issue their own international currencies, the sustainability and “exploitability” of the international role is not absolute. The country that has the greatest fiscal and monetary space is the United States, which issues the predominant key currency, the US dollar. Whereas Wray has written that the predominance of the dollar is not something we will need to worry about in our lifetime, historical and empirical evidence suggests that even considerable forces for persistence of key currency positions can weaken over time, perhaps even rapidly and dramatically …

A note

It’s usually assumed that fiscal sustainability is the condition on the rate of interest, r, and the rate of growth, g. However Wynne Godley showed that it is neither necessary or sufficient. You can read more here from my blog.