Sergio Cesaratto has a new paper Balance Of Payments Or Monetary Sovereignty? In Search Of The EMU’s Original Sin – A Reply To Lavoie. (html link, pdf link)

I obviously agree with Sergio Cesaratto.

As long as there is no supranational fiscal authority, a Euro Area nation’s economic success is more restricted by its exports than otherwise as there is no mechanism for fiscal transfers. The European Central bank can of course backstop and to some extent it has done so, but it cannot let fiscal policy of nations become independent of balance of payments beyond a certain extent. If it does so, nations’ public debt will rise together with net indebtedness to foreigners relative to output and this will become unsustainable. The European Central Bank (the Eurosystem less the domestic National Central Bank) will become a huge creditor and this will not be acceptable to the rest of the Euro Area. (There is of course the question whether this would be morally right but I do not think it is immoral beyond a limit).

To some extent, Mario Draghi has acted the opposite and pushed austerity, but one cannot assume unlimited power for the ECB (Eurosystem to be precise).

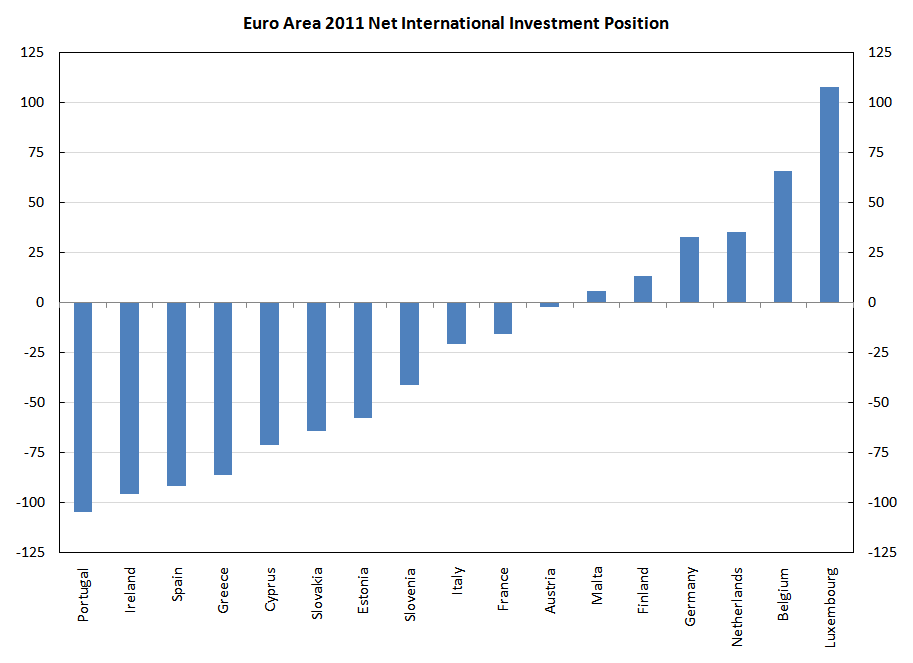

The other way to check that it is indeed a balance-of-payments crisis is to simply see the net international investment position of nations. This chart is from 2011 (intentionally chosen to be old).

The nations troubled most had huge net indebtedness to foreigners. If it is not a balance-of-payments crisis, how does one explain that countries such Germany and Luxembourg had far less troubles than Greece and Portugal?

Abstract of the paper:

In a recent paper Marc Lavoie (2014) has criticized my interpretation of the Eurozone (EZ) crisis as a balance of payments crisis (BoP view for short). He rather identified the original sin “in the setup and self-imposed constraint of the European Central Bank”. This is defined here as the monetary sovereignty view. This view belongs to a more general view that see the source of the EZ troubles in its imperfect institutional design. According to the (prevailing) BoP view, supported with different shades by a variety of economists from the conservative Sinn to the progressive Frenkel, the original sin is in the current account (CA) imbalances brought about by the abandonment of exchange rate adjustments and in the inducement to peripheral countries to get indebted with core countries. An increasing number of economists would add the German neo-mercantilist policies as an aggravating factor. While the BoP crisis appears as a fact, a better institutional design would perhaps have avoided the worse aspects of the current crisis and permitted a more effective action by the ECB. Leaving aside the political unfeasibility of a more progressive institutional set up, it is doubtful that this would fix the structural unbalances exacerbated by the euro. Be this as it may, one can, of course, blame the flawed institutional set up and the lack an ultimate action by the ECB as the culprit of the crisis, as Lavoie seems to argue. Yet, since this institutional set up is not there, the EZ crisis manifests itself as a balance of payment crisis.

Excerpt from the conclusion:

… To conclude, since the EZ is closer to a fixed exchange rate regime rather than to a viable, U.S.-style CU, the euro-crisis is akin to a classical BoP crisis. True, the existence of T2 and the possibility of some ECB backing to troubled local sovereign debts make some difference. However, the limits to an ultimate action by the ECB in connection to the absence of other institutions that compose a viable CU render its action necessarily restricted. One can, of course, blame the lack of these institutions and of an ultimate action by the ECB as the culprit of the crisis, as Lavoie and De Grauwe seem to maintain. Yet, since those institutions are not there, the EZ crisis manifests itself as a balance of payment crisis …

Finally, remember the balance-of-payments constraint manifests itself as lower domestic demand and output as much as financial crises.

In general — in other institutional setups, the importance of the government’s power to make drafts at its central bank is exaggerated. It is highly important of course, but problems of balance-of-payments restrain the power of governments in having a fiscal policy independent of what is happening in international trade. In the Euro Area, the lack of critique of the “Common Market” is striking. One can however see these discussions in the works of Nicholas Kaldor.

Unlimited TARGET2 power?

An important point in the current discussion is around the issue of limits of TARGET2. It is true that the TARGET2 system has large powers to absorb imbalances. The intra-Eurosystem debts need not be collateralized. However, when there is capital flight from a nation, banks become more indebted to their NCB. This process can go on for a long time but ultimately it is restricted by collateral banks can provide to their NCB for replenishing lost settlement balances. There is of course the ELA, Emergency Loan Assistance, but this too is limited beyond a point. There is a lot of politics involved here with some nations complaining unfairly on debtor nations’ use of the ELA, but beyond a certain point, their complaints may be fair.

To summarize, TARGET2 is a big shock absorber: beyond what any economist may have expected, but it cannot absorb shocks beyond a limit.