Earlier I had two posts on this and now I have merged them. (Feb 16 2014, 2:41am UTC)

Tyler Cowen has a blog post which dismisses the idea that distribution of income has an effect on aggregate demand – in particular payment of interest on debt. Merijn Knibbe has a post at the Real World Economics Review blog arguing Cowen is incorrect but Knibbe’s argument is not so accurate.

How does high debt and/or higher interest payments have contractionary effects of aggregate demand?

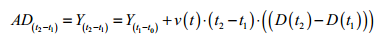

First, if interest rates are constant, increased borrowing for expenditure on goods and services although will initially lead to a rise in aggregate demand, at some point interest payments will start to become important to have a reverse effect if debt rises too high compared to income. The interest payments flow either to banks and other lenders who will pay dividends or they flow to the holders of the securitized loans. The ultimate beneficiary will be households. The households who have received the dividends or interest payments are presumably richer anyway and have a lower propensity to consume compared to households with lower income and hence an effect on aggregate demand.

Second, if there is a rise in interest rates, there is an additional effect even if debt/income isn’t changing as higher interest is paid on floating rate loans such as household mortgages, and this will lead to a fall in consumption than before. This then has a negative effect on aggregate demand. Of course a rise in the rate of interest itself has some effect on borrowing and hence aggregate demand but here we are talking of interest payments only. (There are also other effects such as fall in wealth because a rise in interest rates may lead to a fall in bond prices leading to a fall of wealth of holders and the resultant wealth effect but this is not important for this post).

Of course in general there are several moving parts, and one has to be careful: for example, “negative effect” doesn’t mean a fall.

Knibbe’s argument is however different:

When you pay back your debt to an MFI the asset side as well as the liability side of the balance sheet shrinks with the same amount as respectively the liability side and the asset side of the household or company which pays back the debt. And the money has gone – into thin air. In the case of a pension fund, however, only the composition of the asset side changes as ‘debt’ assets are changed for ‘money’ assets.

and that

… The amount of money decreases. The money does disappear from the stream of aggregate demand.

That isn’t a right argument because banks pay dividends out of profits and that too has an effect on the money stock. Also the destruction of money is not too relevant here. What matters is how much the propensity of consume of the households receiving the dividends is. So the net effect depends on how much the differences in propensities of the various economic units relevant here are.

Also in his post, Knibbe seems to make a distinction between banks and pension funds, as if borrowing from banks has a different effect on aggregate demand than borrowing from some non-bank lender – which is not a good intuition and is essentially a mix of loanable funds model and endogenous money model.

A lot of people misread the notion “loans make deposits”. Those arguments are important to discard the textbook model of the money multiplier but it is sometimes implicitly extrapolated to various incorrect notions. One should look at the stock of money from something such as Tobin’s asset allocation model rather than thinking creation of money being synonymous to increase in aggregate demand. In general a rise in borrowing for expenditure on goods and services (both from banks and non-banks) leads to a higher output and income and hence higher wealth of asset allocators who would want to hold a higher amount of deposits (because their wealth has risen) and this will to a higher stock of money than the recent past. So the higher stock of money will then be coincident to higher output but cannot be said to have been the reason for an increase in aggregate demand or output. Similarly a fall in the stock of money cannot be said to be cause of a fall in aggregate demand. So high interest payment on debts has an effect on aggregate demand and output via the distribution of income and not because bank deposits reduce at the moment interest is paid.

Addendum

After I posted the above, I received a nice comment by Kostas Kalevras according to whom not all profits of are paid as dividends and there are additional complications that it matters what the counterpart of the saving is – whether in the form of capital formation or accumulation of financial assets.

Normally it is said saving is a leakage to demand but this is not right. For a firm, the retained earning in any period – i.e., the undistributed profits are its saving. But as Kostas points out, net lending is important. To see this imagine two firms – same retained earning but one with accumulation of fixed capital such as buildings and another accumulating financial assets as counterpart to the retained earning. The first firm has a higher contribution to demand because of the investment expenditure. And net lending/net borrowing is the thing to look at.

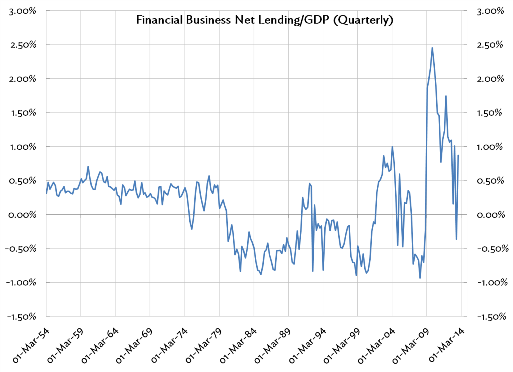

For financial firms, the difference in saving and net lending will be small, but let’s still take net lending. So here is the chart obtained by the Federal Reserve’s Z.1 Flow of Funds data for the United States:

Net lending increased during the crisis but has dropped again.

So we have come a long way from interest payments on debt completely disappearing. Dividends distributed are income for shareholders, as are interest payments on bonds issued (or loans taken) by these firms (even wages and other costs) and it matters to whom it flows and their propensities to consume. Also the additional important complications noted above. (Of course since now I am talking data, payments to foreigners also matters but that’s not important for now).