… and politics and ideology will seep into it.

Tom Hickey writes a nice reply to Noah Smith’s blog post How Normal People See Macroeconomics.

Smith says:

I’ve been thinking about these differences for a while, and I’ve reached two major conclusions:

1. Normal people see macro as inherently political.

2. Normal people see macro as being mostly about redistribution rather than about efficiency….

The whole essay is like economists are doing something value free and that politics is not important. Joan Robinson nicely summarized the situation in her essay What Are The Questions (jstor URL):

The movement of the thirties was a attempt to bring analysis to bear on actual problems. Discussion of an actual problem cannot avoid the question of what should be done about it; questions of policy involve politics (laissez-faire is just as much a policy as any other). Politics involve ideology; there is no such thing as a “purely economic” problem that can be settled by purely economic logic; political interests and political prejudice are involved in every discussion of questions. The participants in controversy divide themselves in schools – conservative or radical and ideology is apt to seep into logic. In economics, arguments are largely devoted, as in theology, to supporting doctrines rather than testing hypotheses.

Smith writes as if what he is doing is good for the society as a whole – despite the fact that his own colleagues are pushing their own ideologies in policy which is bad for society as a whole.

Smith also writes:

Many people see the “-isms” of macro – “New Keyneisanism”, “New Classicalism”, etc. – as political advocacy rather than as dispassionate scientific attempts to explain the world around us….

But it is right – people like Greg Mankiw have pushed their agendas. What is wrong with “normal people’s view” on this? They are exactly right. Mankiw’s defending the 1% is a dispassionate scientific attempt?

And the above Robinson quote is actually a dispassionate description of the situation than Smith’s own!

Who is Smith trying to fool here?

In fact,

One of the main effects … of orthodox traditional economics was … a plan for explaining to the privileged class that their position was morally right and was right for the welfare of society.

– Joan Robinson, 1937, “An Economist’s Sermon”, Essays In The Theory Of Employment, The Macmillan Company

Smith also writes:

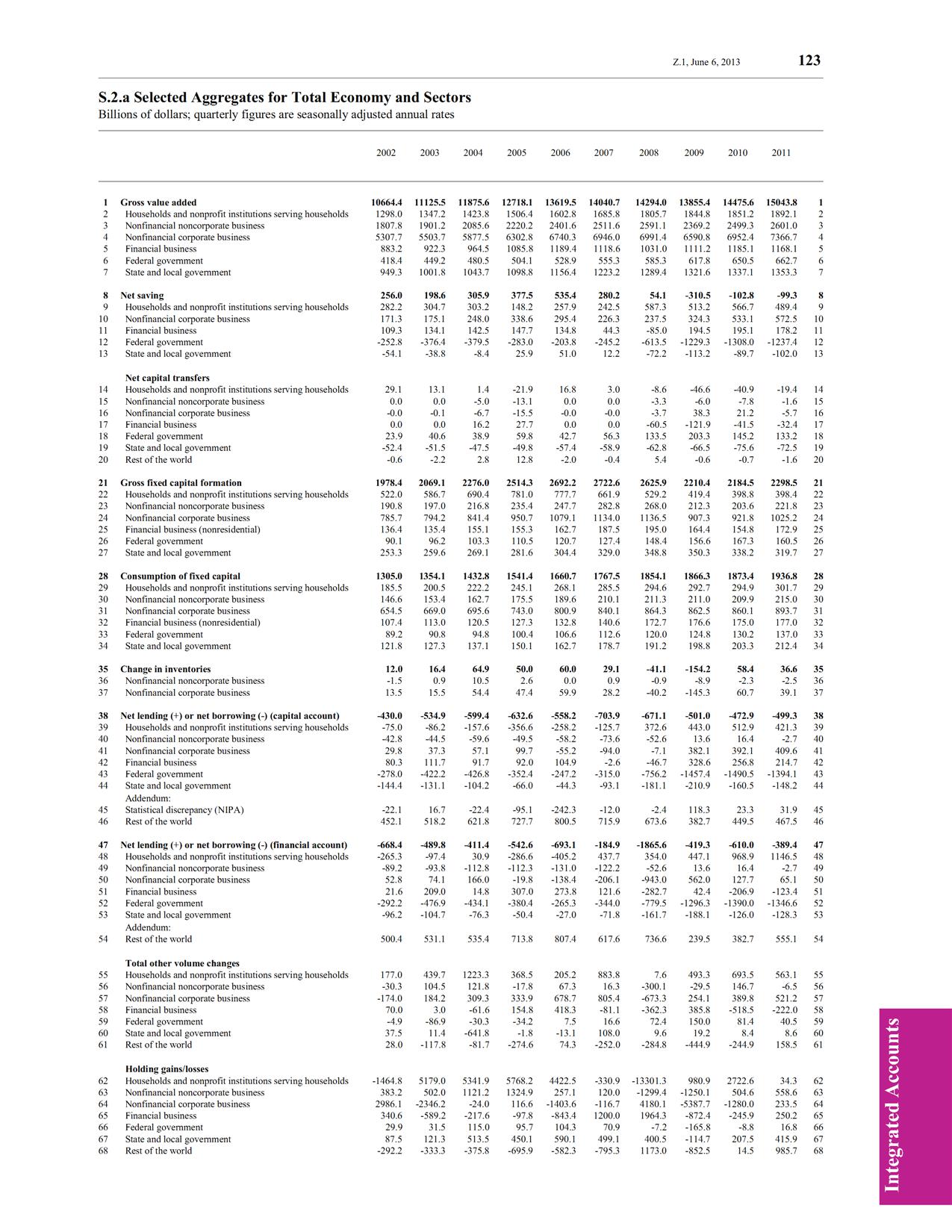

If monetarists or New Keynesians (is there a difference?) suggest monetary expansion, for example, a lot of readers see it instead as a liberal attempt to use inflation to redistribute money from rich creditors to poor debtors, while a few see it as a conservative attempt to boost the profits of big banks. Only a small minority seem to consider the question of whether monetary expansion is a Pareto efficient response to the business cycle. Because of this, monetarists like Scott Sumner often spend a lot of time “punching hippies” on every issue other than monetary policy, trying to avoid being tarred as hippies themselves for their lack of fear of inflation.

Whatever Pareto efficiency is. But it is mainstream economists themselves who have promoted deflationary policies by selling them to the public that such policies are good for them. Monetarism was a scourge in the 1980s and has permanently distorted economists and the common man. Now he completely avoids history and presents the case as if (mainstream) economists want a rise in demand, not the normal people!