Always helps to look at actual data and remember it.

From the IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook:

(click to expand)

Far away from rebalancing!

Always helps to look at actual data and remember it.

From the IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook:

(click to expand)

Far away from rebalancing!

There have been too many praises for Mrs Thatcher after her death today.

Wynne Godley once described the Thatcher “miracle” as a gigantic con-trick. Here is from a newspaper article:

I regard the Thatcher miracle as a gigantic con-trick. Almost every major indicator – output, unemployment, industrial investment, and the balance of payments has performed poorly over the nine Thatcher years taken as a whole … The ‘con’ trick has been achieved by the enrichment of part of the community at the expense of a minority, by skilful but thorougly dishonest presentation of the facts, by the ruthless use of patronage and the exploitation of an ugly vein of populism in the British people.

– Wynne Godley in Why I Won’t Apologize, September 18, 1988, Observer.

The article scan is below:

Wynne Godley, Why I Won’t Apologize

(click to enlarge and click again)

Also see the papers which describes the right facts:

Thatcher’s bluff was caught very early by Godley. The huge rise in unemployment (to 3 million) was predicted first by Wynne Godley himself in 1979.

Reference: Godley W., ‘Britain’s chronic recession-can anything be done?’ in W. Beckerman (ed.) Slow Growth in Britain, Oxford University Press, 1979.

His King’s College Obituary (Annual Report, 2011) had this to say about Thatcherism:

Wynne rather relished his reputation as the ‘Cassandra of the Fens’. He famously made a double prediction: that under current policies of the first Thatcher government unemployment would inevitably rise to three million, but – the second prediction – that this would not in fact happen, on the grounds that, since in post-war Britain three million unemployed had to be an electoral suicide note, the policies would have to be changed. He was right with the first prediction, and – misreading the not-for-turning dispositions of the Iron Lady – wrong with the second. The actual outcomes appalled him. For Wynne the fundamental economic responsibility of a government was to ensure ‘full employment’. In pursuit of that aim he was uninhibited as Keynes himself and perhaps rather close in his motivation. He believed it was essential to use fiscal levers to stimulate demand, and was even prepared – though under very strict conditions – to countenance temporary import controls to protect and strengthen economic activity. His ideas were controversial and, like the man himself, often stood at an odd angle to the contemporary world, but the moral imagination which informed them was large and generous.

Eine neue wissenschaftliche Wahrheit pflegt sich nicht in der Weise durchzusetzen, daß ihre Gegner überzeugt werden und sich als belehrt erklären, sondern vielmehr dadurch, daß ihre Gegner allmählich aussterben und daß die heranwachsende Generation von vornherein mit der Wahrheit vertraut gemacht ist.

Translation: A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.

– Max Planck.

The variant of this is “Science advances one funeral at a time.”

Margaret Thatcher passed away today but Thatcherism still survives and dominates policy debates. So perhaps Max Planck doesn’t seem to apply to economics yet in a straightforward way.

The best opposition to Thatcherism came from Cambridge. In a small book based on speeches in the House of Lords (1979-1982) The Economic Consequences Of Mrs Thatcher and devoted entirely to pin-pointing the fundamental errors of Thatcherism, Nicholas Kaldor wrote in this in a chapter titled The Economics of the Primitive (18.3.81), page 83:

The belief that public expenditure must be cut in order to balance the budget, which is clearly held passionately by Mrs Thatcher and her immediate associates, derives from an anthropomorphic conception of economics. Primitive religions are anthropomorphic. They believe in gods which resemble human beings in physical shape and character. Mrs Thatcher’s economics is anthropomorphic, in that she believes in applying to the national economy the same principles and rules of conduct as have been found appropriate to a single individual or a family – paying your way, trimming your expenditure to fit your earnings, avoiding living beyond your means and avoiding getting into debt. These are well-worn principles of prudent conduct for an individual but when applied to policy prescriptions to a national economy they lead to absurdities.

If an individual cuts his expenditure he will not thereby reduce his income. However, if a Government cut their public expenditure programme in relation to tax rates and charges, they will reduce the total spending in the economy and hence the total production and income. It will reduce the revenue yielded by existing taxes and it will cause public expenditure on unemployment benefits and on the support of firms in trouble, and other similar items, to rise. It is a policy that is appropriate only in times of excess demand and over-full employment, as was the case with Crippsian austerity after the war. At a time like now, with 2½ million unemployed, far from being a recipe for prudent housekeeping and future prosperity it is a recipe for ruin. To keep tightening the budget in the hope of ‘balancing the books’ is to keep reducing the output and income of the nation and hence to fail to balance the books as tax yields shrink and expenditures to support the disintegrating economy increase.

The word “prudent” still survives to this day and perhaps heard more often, in politicians’ and central bankers’ speeches, research reports of financial markets’ “experts” and in the media and in rating agencies pressuring government to tighten fiscal policy.

Update: Here is John Boehner repeating Thatcherism on Twitter:

click to view on Twitter

A lot of heterodox economists are sympathetic to Paul Krugman because he seems to have argued for fiscal expansion.

Ha!

First, we are in this mess because of people like Paul Krugman who has promoted free trade – which has been destructive to the world economy as a whole and has prevented debtor nations from engaging in fiscal expansion to reflate their economies. The creditor nations won’t reflate their economies by fiscal expansion so easily – just barely the minimal needed to prevent social tensions from building up – because they don’t want to become debtors down the road. They overdo this but free trade has created this situation in the first place.

This crisis has made nations realize the importance of exports in growth and nations will want to improve their international investment position should there be growth in the rest of the world and they will want to wait sufficiently for exports to improve before expanding domestic demand. This creates a game theory like problem for growth of the world as a whole.

Now, Krugman is a smart man. He will make it look as if he was not all that dogmatic. And now ridicules everyone who opposes fiscal expansion. While it is good in a sense because the world needs a worldwide fiscal expansion (but this needs to be coordinated at least), it is nowhere close to the simplistic solutions Krugman presents with his comical IS/LM diagrams and liquidity trap theories and confusions with his notions of exogenous money – which is only a smart way of defending his earlier positions – even though we hear frequent Mea Culpas on his blog.

I came across this article by William Greider – Why Paul Krugman Is So Wrong in which he reminds the readers of how the mania of free trade has been promoted by Paul Krugman and how he has ridiculed everyone showing dissent.

It is generally nice in parts and is worth reading. I like the part in which Greider says that even though free trade has created problems for the United States, it wants to get out of the problems by promoting more free trade!

I am also reminded of a sacred tenet article of Paul Krugman making the case for free trade. The article titled Ricardo’s Difficult Idea not only ridicules anyone arguing against free trade but also gives out strategies on how to promote it.

Here is one paragraph which is worth quoting:

During the NAFTA debates I shared a podium with an experienced, highly regarded U.S. trade negotiator, a strong NAFTA suppporter [sic]. At one point a member of the audience asked me what I thought the effect of NAFTA would be on the number of jobs in the United States; when I replied “none”, based on the standard arguments, the trade official exploded in anger: “It’s remarks like that which explain why people hate economists!”

I like this quote by Francis Cripps from an article in The Guardian from 27 Feb 1979: Economists With A Mission:

Cyprus has recently received the attention of academicians and financial professionals in recent weeks. Need I say that?

So national bankruptcy is to be resolved by winding down a bank, moving guaranteed deposits (i.e., upto €100,000) to another and as per the latest Reuters article on this, big numbers (anywhere ranging from 20 to 40 per cent loss on deposits on amounts over €100,000) are quoted.

Martin Wolf has a good summary:

The current plan is closer to what one would wish to see in an orderly bank resolution. Laiki Bank is to be split into good and bad banks. Deposits of less than €100,000 in the bank and assets worth €9bn – the sum owed to the central bank as part of its liquidity support – will be transferred to Bank of Cyprus. The remainder will be wound down. Those with claims to deposits in excess of €100,000 will obtain whatever the value of the bad bank’s assets turns out to be.

Meanwhile, savers at the Bank of Cyprus with deposits of more than €100,000 will have their accounts frozen and suffer a “haircut” of still unknown size. That reduction in value is likely to be large: perhaps 40 per cent. Finally, temporary exchange controls are to be imposed.

Why are the reasons for such huge numbers?

The reason is that the nation has accumulated huge net indebtedness to foreigners over years and this has been financed by banks raising deposits from foreigners, so that if debt traps are to be avoided, foreigners are to be required to take losses.

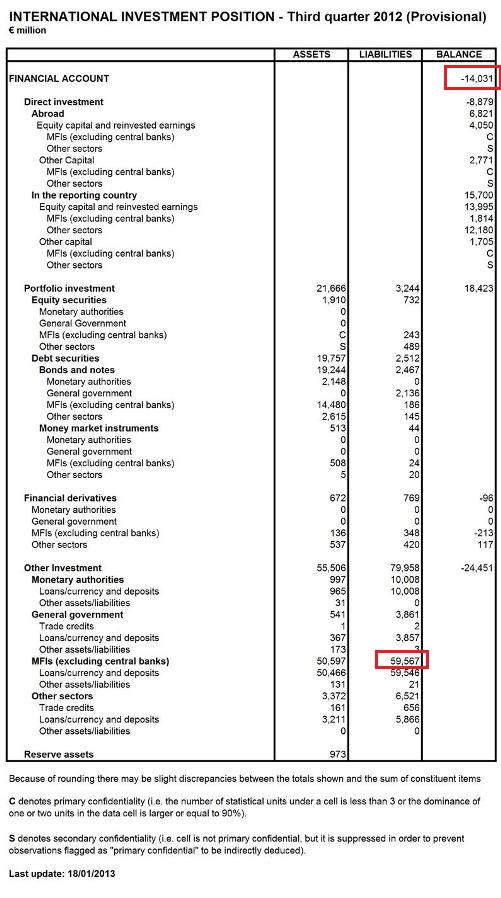

The following is the international investment position of Cyprus at the end of Q3 2012 (source: Central Bank of Cyprus)

In the balance of payments literature, banks’ position is referred as Other Investment. Also, the above refers to a Financial Account but it really means net IIP. Ideally it would have been better if this data had been updated but the above information is useful nonetheless.

In the balance of payments literature, banks’ position is referred as Other Investment. Also, the above refers to a Financial Account but it really means net IIP. Ideally it would have been better if this data had been updated but the above information is useful nonetheless.

As a percent of gdp, the net IIP position (with the opposite convention to standard usage) was 81.1% (Source: Eurostat) which is big in itself but very much lower than the now famous banks’ liabilities to foreigners/Russians! (the second red box above).

If a nation wants to resolve bankruptcy, it is better to do it by imposing losses on foreigners – especially if an international lender of last resort is available! And if this is to done it in the optimal way, best to do it once – rather than keep doing it. The ratio of two red boxes in the table – i.e., net liability as a proportion of gross bank liabilities to foreigners is 24.56%.

So Cyprus needs to wipe out about this amount as a percent of deposits roughly. It is not necessary to reach a position of zero indebtedness but something low such as 10% of gdp is ideal. Some buffer is needed because there will be leakages in spite of capital controls – requiring fire sale of foreign assets (and subsequent losses) by banks or borrowing from the ECB which may want to ensure that banks have good collateral for the ELA. Foreign deposits below €100,000 shouldn’t be hit. So “net-net”, as a percentage, this may be higher than 24.56%. All this depends on the latest situation and the distribution of foreign deposits and also the distribution between residents and foreigners but 24.56% of deposits is a good starting point – it gives a rough estimate of the order of magnitude of the problem.

At any rate, losses imposed on foreigners have to be big for the ECB and Euro Area governments to stand behind.

Recently I have come across many people saying S = I is not correct or that it is valid only for a purely private economy.

People who come across the sectoral balances identity

S − I = G − T + CAB

sometimes mix up with another macroeconomic identity

S = I

They are unsure of the correctness of each or the kind of setup one or the other is valid. Or – how can both be valid?

The reason both are valid is that the former is a sectoral equation and the S refers to the private sector saving and in the latter, S refers to the sum of savings of all sectors of the world*.

Remember good authors always specify the terminology used and you should too always.

But the first equation doesn’t make the second equation invalid. It is just that the contexts are slightly different.

So in the first equation, S is the private sector saving, I is private sector investment and G is the government expenditure, T is tax receipts of the government and CAB is the current account balance of payments.

So, in case you want to use the two simultaneously, use different notations.

Take an example of a closed economy.

The government’s expenditure is comprised of current and capital expenditures.

So,

G = Gcurrent + Igovt

Government’s saving is T − Gcurrent

So

Spriv − Ipriv = G − T = Igovt − (T − Gcurrent)

and hence

Spriv − Ipriv = Igovt − Sgovt

So,

Spriv + Sgovt = Ipriv + Igovt

which is written as S= I in short by authors – which is fair because they assume a context.

There is source for further confusions. This is because of mixing of the same set of symbols for planned investment and planned saving with the recorded ones. Clearly, planned investment needn’t be equal to planned saving. However, it is always good when discussing ex-ante and ex-post variables to use different symbols.

Some authors mix notation everywhere in their analysis, and call others confused!

If one doesn’t keep track of notations, a more complicated analysis will produce nonsensical results.

If someone doesn’t understand this, his confusions are his problems, not others’.

—

*Savings used as a plural of saving and as a flow instead of informal terminology referring to a stock

When an economist talks of the “price mechanism”, it can be assumed that his theory is bunkum. Of course, it doesn’t mean that prices don’t play a role but the role played is entirely different than what the raw intuition of a normal person or the learned intuition for neoclassical economists says. Economists – neoclassical and their cousins – also talk of a Walrasian auctioneer whose role is to collect preliminary buy and sell orders, which he uses to find the “clearing” price. A look at the microstructure of markets reveals this is quite misleading and very incorrect inferences can be drawn from the price clearing story.

The blogger Lord Keynes (!) has a nice post quoting Nicholas Kaldor – mainly from his 1985 book Economics Without Equilibrium – The Okun Memorial Lectures At Yale University.

The following is from pages 13-18 – which have great insights on this. It draws heavily from Kaldor’s own paper from 1939: Speculation And Economic Stability.

Perhaps for that reason general equilibrium theory retains its fascination for teachers and students of economics alike. Indeed, judging by the number of Ph.D. students working on the implications of the rational expectation hypothesis, it is gaining ground, at any rate, in America. One reason is the intuitive belief that the price mechanism is the key to everything, the key instrument in guiding the operation of an undirected, unplanned, free market economy. The Walrasian model and its most up-to-date successor may both be highly artificial abstractions from the real world but the truth that the theory conveys — that prices provide the guide to all economic action — must be fundamentally true, and its main implication that free markets secure the best results must also be true. (This second proposition was indeed demonstrated but under assumptions so restrictive that Professor Hahn turned the argument around and suggested, in his inaugural lecture, that the importance of general equilibrium theory lies precisely in showing how stringent the conditions must be for “free markets” to secure the results in terms of welfare that are naively attributed to them. This may well be true, but if so, it is truth bought at a very high cost.)

But the basic assumptions in all this — that prices are very important in the working if a market economy — is rarely, if ever questioned. Yet it is precisely this over-emphasis on the role of the price system that I regard as the major shortcoming of modern neoclassical economics, particularly the Walrasian version of it.

The Role of Dealers and Speculators

Walras knows only two categories of “agents”: producers and consumers. He makes no mention of the third category which is vital to the functioning of any market economy, namely, the “dealer” or “middleman” (or “merchant”) who is neither buyer not seller, because he is both simultaneously. It is the dealers or merchants who make a “market” which enables producers to sell and consumers to buy, and who carry stocks of commodity the deal in in large enough amounts to tide over any discrepancies between outside sellers and outside buyers over any short period of time, and in practice fulfill the role designed for the “heavenly auctioneer” since they are the people who at any moment of time quote prices for purchases or for sales. They are not required under actual rules to buy or sell only at “equilibrium” prices — whatever that is taken to mean — though there are special markets, like the London bullion market, where the actual dealing price is struck after ascertaining the demands and the offers of dealers at various prices. (This is possible when, as in the London gold market, everybody’s demand and supply can be handled through a small number of dealers.) At any given moment of time, or to be a little more realistic, at the start of business, say the first thing in the morning, all prices are given to them as a heritage of the past. The important thing is that it is the dealers who initiate the price changes necessary for aligning, or rather realigning, the demand of the consumers and the supply of producers. They make their living on the “turn” between the buying price and the selling price; and the larger the market and the greater the competition between dealers, the less this “turn” is likely to be, as a proportion of price (always provided that the “turn” must be large enough to cover interest and carrying costs on stocks plus some compensation for the risk of a fall in market prices in the future). Thus buying or selling necessarily involves transaction costs that cannot be said to fall on the seller any more than on the buyer; they are divided between them, but it is not meaningful to ask how much falls on one side rather than the other.

Any discrepancy between sales and purchases (or “outsiders,” that is, of producers and consumers) is simultaneously reflected in the stocks (or “inventories” to use the American term) carried by merchants. Experience has taught them how large their “normal” stocks need to be in relation to their turnover in order to ensure continuity of dealing, for a dealer’s reputation (or good will) depends on his ability to satisfy his customers at all times; refusal or inability to deal is likely to divert business to others. They protect their stock by varying both their buying and selling prices simultaneously, raising prices when stocks are falling and lowering them when they are rising.

The size of price variation induced by a change in the volume of stocks held by the market depends on the dealer’s expectations of how long it will take before prices return to “normal” and how firmly such expectations are held. Even before the Second World War, the short-term fluctuations in commodity market prices (i.e., the markets of the staple agricultural and industrial raw materials, including metals) were very large. According to Keynes’s calculations in 1938 (in an article in the Economic Journal)* the average annual variation in the ten previous years between the lowest and the highest prices in the same year in the case of four commodities (rubber, cotton, wheat and lead) was 67 percent. Unfortunately, the corresponding figures for the fluctuations in stocks carried that were associated with these prices variations could not have taken place unless there were frequent changes in the prevailing expectations concerning future supplies of demands.

* “ The Policy of Government Storage of Food Stuffs and Raw Materials.” Economic Journal, September 1938, pp. 449-460

Nor is it known how far the price movements were exaggerated as a result of the activities of yet another class of “agents”, the speculators. Professional dealers act under the influence of price expectations, and to that extent their market behavior can also be regarded as speculative in character. But their actions are motivated by the desire to reduce the risks facing them (which they inevitably assume as dealers) by their willingness to reduce their stocks in times of high prices and the opposite willingness to absorb extra stocks when prices are regarded as abnormally low. In any case the risks they carry are an inevitable by-product of their function as dealers. Speculators on the other hand assume risks for the sake of a gain and thereby provide facilities for hedging by buying “futures” from those who are committed to carry stocks of a commodity, and selling “futures” from those who are committed (by their productive activities) to acquire commodities in the future for uses for which they have already entered contractual commitments.

The activities of both dealers and speculators are supposed to smooth out both fluctuations in prices and variations in the size of inventories. Price rises should be moderated by the reduction of inventories held by dealers; similarly, a price fall should be moderated by a consequential increase in inventories. As Arthur Okun pointed out in one of his papers, * as a matter of “stylized fact” this is the very opposite of what actually happens.

The hallmark of U.S. postwar recessions has been inventory liquidation, following a major buildup of inventories at the peak of the expansion. Standard models that assume price-taking and continuous market clearing do not suggest that a disappointment about relative prices will lead to liquidate inventories. For example, a sudden drop in the demand for, and hence the price of wheat that leads farmers to decrease production in the future will generally lead traders to increase stocks initially. (The price tends to fall enough currently relative to its new future expected value to provide traders with that incentive.) Why then, in the business cycle, is an aggregate cut back in production accompanied by a cutback in stocks?

*Rational Expectations with Misperceptions As a Theory of the Business Cycle, proceedings of a seminar held in February 1980 and printed in the Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, November 1980, Part 2]

This was mentioned as the first of eight “stylized cyclical facts” that Okun regarded as inconsistent with the rational expectations hypothesis; it related to the behavior of a special class of “agents” whose main business it is to be rational in their expectations.

All this related mainly to the behavior of commodity markets which come nearer to the “auction markets” of general equilibrium theory than all the other “markets” in the economy. Yet they fail to satisfy the theoretical requirements from more than one point of view. First, they are not “market clearing” in the sense of equating demand and supply on the strict criterion that the maximum amount sellers desire to sell at the ruling price is equal to the maximum buyers desire to buy. There is a change in inventories from period to period, held by insiders in the market, that is quite un-Walrasian – it means that demand was either in excess of, or short of supply-the market has not “cleared” and the transactions, even in the shortest of periods, such as a day or even an hour, did not take place at a uniform price but at prices that varied sometimes minute by minute.

Nicky Kaldor from the back cover of Economics Without Equilibrium

On 28 Feb, FT’s columnist Chris Giles attacked the United Kingdom Office of National Statistics in his article titled UK’s official statistics cannot be trusted.

As his title suggests, Giles argues that the ONS is helping the UK government hide some public finances statistics and is losing its independence. His article is misleading to say the least.

Also see Jil Matheson’s reply to FT.

To see this one needs to understand some national accounts concepts. Usually economists and journalists err on simple concepts and Chris Giles does the same – leading him to his strange conclusions.

The government’s deficit is the difference between its expenditures and income (mainly taxes). The difference is financed by borrowing from the markets. This used to be called the PSBR – Public Sector Borrowing Requirement. The government also earns from the central bank’s profits. During any period of measurement however, the government also rolls over its maturing debt and the nomenclature changed to PSNB – public sector net borrowing.

So we had

G – (T + Fcb) = PSNB

where G is the government expenditure including interest payments (and including interest payments to the central bank), T is tax receipts and is the Fcb profits of the central bank (assumed to be remitted in full to the Treasury for simplicity). However, during the financial crisis, the UK government needed to bailout banks and to finance its purchases of newly issued equities, it needed to borrow more. Hence the above relation was no longer valid.

So

G – (T + Fcb) ≠ PSNB

However, the deficit is fundamentally the left hand side. The purchase of equities cannot be thought of as adding to the government’s deficit because the government acquires financial assets in return. Of course this adds to PSNB and hence also to the public debt. So to measure the real effects, the UK ONS proposed a measure PSNBex.

G – (T + Fcb) = PSNBex

This is as it should be – the bailout of banks by purchases of its newly issued equities cannot be said to be equivalent to an expenditure by the government which has a direct effect on aggregate demand. The bailout of banks although has its benefits – in the sense that they will be less constrained in lending – has an indirect effect and it will be captured when banks lend for a house purchases and this will reflect in investment expenditures. Of course the bank bailout has to appear somewhere in the accounts and it does and the UK ONS has been careful in doing it the right way.

In the Euro Area however, this is captured differently in national accounts and this is not the best way in the spirit of the accounts. So when the Irish government bailed out banks, it was measured as a huge rise in the deficit.

So here is from the Eurostat for the year 2010 and you can see Ireland visibly:

(Source: Eurostat. Click to enlarge)

Back to UK national accounts.

Assuming bailouts are in the past, i.e., not in the period of recording and also assuming no sale of equities by the government,

G – (T + Fcb) = PSNBex = PSNB

Now, the Bank of England has been has been purchasing government bonds in open markets as part of its Asset Purchase Facility program (strange word “facility”). It established a fund (or a financial vehicle) called Bank of England Asset Purchase Facility Fund Ltd which funded its purchases of UK government bonds by borrowing from the Bank of England. Over time, the BEAPFF has made profits on its operations and this is reflected in its cash balances at the Bank of England. The UK Treasury recently decided to transfer the cash to its own account (“raid” in the words of Chris Giles).

The cash transfer is an income flow from the Bank of England to the Treasury and hence reduces the PSNBex.

The ONS came with a technical note on how to measure this and Giles decided saw it as a proof that the ONS is not independent!

Although these effects seem intra-government, national accounts (SNA) treats the central bank as part of the financial sector and hence the transfer of the cash from BEAPFF reduces the PSNBex. Hence according to the ONS:

Following recommendations from the National Accounts Classification Committee (NACC), The Public Sector Finances Technical Advisory Group (PSFTAG) and Eurostat, it has been decided that:

- The Asset Purchase Facility will continue to be treated as part of the Bank of England in National Accounts and Public Sector Finance statistics.

- The flows of cash from the BEAPFF to HM Treasury, up to the level of the combined Bank of England’s ‘Entrepreneurial Income’ from the previous year, are treated as final dividends and therefore reduce the level of General Government Net Borrowing by that amount. However, anything above this level will be treated as a special transaction in equity, known as a super-dividend, which will not impact on the level of General Government Net Borrowing. (This calculation is known as the super-dividend test.) Whatever the impact on General Government Net Borrowing, the full value of the payments will impact on the General Government Net Cash Requirement.

- Any flows of cash from HM Treasury to the Bank of England in the future to cover losses made by the BEAPFF will be treated as Capital Transfers and so will impact (in the opposite direction) on measures of General Government Net Borrowing and General Government Net Cash Requirement.

- The BEAPFF as a whole should remain classified as a temporary effect of financial interventions as the end state of the BEAPFF remains unknown.

- The payments between the Bank of England and Treasury should be treated as permanent effects and therefore impact on the headline measures of Public Sector Net Borrowing (PSNB ex) and Public Sector Net Debt (PSND ex), which exclude temporary effects of financial interventions.

All this is consistent with the principles of national accounts – how the central bank is treated and how various flows are measured and recorded etc. The government interest payment to the BEAPFF increases PSNBex and the cash transfer reduces it.

The ONS says clearly that in case the BEAPFF suffers a loss, there will be a capitalization by the government and this will be treated as a capital transfer and will impact government’s accounts – but in the future.

Yet in spite of very clear thinking and action by the ONS, Chris Giles erroneously concludes that “official statistics cannot be trusted”. His critique is vacuous.

Always start macroeconomics with balance of payments 🙂

Moody’s Investors Service has today downgraded the domestic- and foreign-currency government bond ratings of the United Kingdom by one notch to Aa1 from Aaa.

It also downgraded the Bank of England:

In a related rating action, Moody’s has today also downgraded the ratings of the Bank of England to Aa1 from Aaa.

This has seen a lot of reactions – such as quoted here in an FT Alphaville blog post ‘This downgrade is nonsense!’

So let us get straight to scenarios which lead to defaults – in addition to ones purely voluntary.

Scenario 1.

The easiest is to think of a scenario where the Euro Area forms a political union and the UK is invited to join it and it joins it – such as in 2027. The UK government then gives up the power to make drafts on its central bank and becomes a state level government. UK government bonds will be redenominated in Euro and hence a possibility of default exists – including on debts in existence in 2013.

Scenario 2.

Suppose the UK pegs GBP to some currency such as the Euro or the dollar in 2024. Then surely the government and the central bank can default on debts in existence in 2013 and denominated in GBP in say 2037 isn’t it (like Russia in 1998)?

Now you may complain that it was the government’s mistake to have pegged its exchange rate – but whatever said, an investor holding a bond in 2013 would have been hurt in 2037.

Scenario 3.

Suppose the UK has a balance of payments crisis in 2030. It needs foreign exchanges and needs an international lender such as the IMF. Now suppose the IMF insists that the UK government and the Bank of England default on foreigners holding GBP denominated bonds including those in existence in 2013. Voluntary default?

Conclusion

Moody’s can be criticized for playing political games but a good critique cannot be that default is not possible.

You can come up qualifiers but won’t prove Moody’s rating change wrong.

Don’t get me wrong. I am trying to convince to come up with stronger arguments for critiquing the rating agencies instead of simple ridiculing. Usually the rating actions are defended by people arguing for fiscal contraction. Paradoxically the recovery of the world economy cannot come about easily with without at least a worldwide fiscal expansion.

This looks nice but will be released only in May 🙁

Table of Contents

Preface and acknowledgements

Introduction – G.C. Harcourt and Peter Kriesler

1. A personal view of the origins of post-Keynesian ideas in the history of economics – Jan Kregel

2. Sraffa, Keynes and post-Keynesianism – Heinz Kurz

3. Sraffa, Keynes and post-Keynesians: Suggestions for a synthesis in the making – Richard Arena and Stephanie Blankenburg

4. On the notion of equilibrium or the centre of gravitation in economic theory – Ajit Sinha

5. Keynesian foundations of post-Keynesian economics – Paul Davidson

6. Money – Randall Wray

7. Post-Keynesian theories of money and credit: conflict and (some) resolutions – Victoria Chick and Sheila Dow

8. The scientific illusion of New Keynesian monetary theory – Colin Rogers

9. Single period analysis and continuation analysis of endogenous money: a revisitation of the debate between horizontalists and structuralists – Giuseppe Fontana

10. Post-Keynesian monetary economics Godley-like – Marc Lavoie

11. Hyman Minsky and the financial instability hypothesis – John King

12. Endogenous growth: A Kaldorian approach – Mark Setterfield

13. Structural economic dynamics and the Cambridge tradition – Prue Kerr and Robert Scazzieri

14. The Cambridge post-Keynesian school of income and wealth distribution – Mauro Baranzini and Amalia Mirante

15. Reinventing macroeconomics – Edward Nell

16. Long-run growth in open economies: export-led cumulative causation or a balance-of-payments constraint? – Robert Blecker

17. Post-Keynesian precepts for nonlinear, endogenous, nonstochastic, business cycle theories – K. Vela Velupillai

18. Post-Keynesian approaches to industrial pricing: a survey and critique – Ken Coutts and Neville Norman

19. Post-Keynesian price theory: from pricing to market governance to the economy as a whole – Frederic S. Lee

20. Kaleckian economics – Robert Dixon and Jan Toporowski

21. Wages policy – John King

22. Discrimination in the labour markets – Peter Riach and Judith Rich

23. Post-Keynesian perspectives on economic development and growth – Peter Kriesler

24. Keynes and economic development – Tony Thirlwall

25. Post-Keynesian economics and the role of aggregate demand in less-developed economies – Amitava Krishna Dutt

—

Volume 2 website here

Table of Contents

Preface and acknowledgements

Introduction (from volume 1) – G.C. Harcourt and Peter Kriesler

1. On microfoundations of macroeconomics – Abu Rizvi

2. Post-Keynesian economics, rationality and conventions – Tom Boylan and Paschal O’Gorman

3. Methodology and post-Keynesian economics. – Sheila Dow

4. Critiques, methodology and the relationship of post-Keynesianism to other heterodox approaches – Gay Meeks

5. Two post-Keynesian approaches to uncertainty and irreducible uncertainty – Rod O’Donnell

6. The interdisciplinary applications of post-Keynesian economics – Wylie Bradford

7. Post-Keynesian economics, critical realism and social ontology – Stephen Pratten

8. The traverse, equilibrium analysis and post-Keynesian economics – Joseph Halevi, Neil Hart and Peter Kriesler

9. A personal view of post-Keynesian elements in the development of economic complexity theory and its application to policy – Barclay Rosser Jr.

10. How sound are the foundations of the aggregate production function? – Jesus Felipe and John McCombie

11. Marx and post-Keynesians – Claudio Sardoni

12. The L-shaped aggregate supply curve, the Phillips curve, and the future of macroeconomics – James Forder

13. A post-Keynesian critique of independent central banking – Joerg Bibow

14. The post-Keynesian critique of the mainstream theory of the state and the post-Keynesian approaches to economic policy – Richard Holt

15. A modern Kaleckian-Keynesian framework for economic theory and policy – Philip Arestis and Malcolm Sawyer

16. Classical-Keynesian political economy: genesis, present state and implications for political philosophy and economic policy – Heinrich Bortis

17. Post-Keynesian distribution of personal income and policy – James K. Galbraith

18. Environmental economics – Neil Perry

19. Theorising about post-Keynesian economics in Australasia: aggregate demand, economic growth and income distribution policy – Paul Dalziel and J. W. Nevile

20. The heterodox spiral and the neoclassical sink: reclaiming economic theory after neo-liberalism – Gary Dymski

21. Keynesianism and the crisis – Lance Taylor