Elasticities for one last time for now.

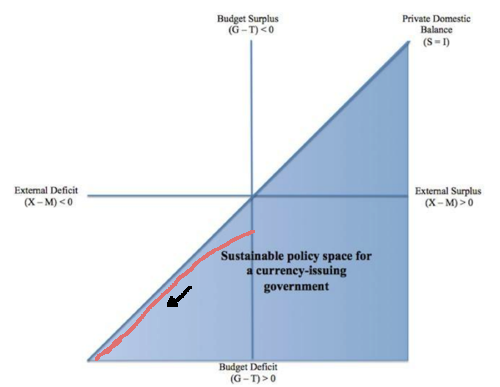

Recently Tom Palley wrote a fine critique of the Neochartalist approach to solve the world problems with oversimplistic solutions. Among other things, Palley challenges the simplistic Chartalist solutions due to dilemmas posed by the external sector.

Bill Mitchell of Australia wrote a reply in which he states the following:

It is easy to see that a Job Guarantee model requires a flexible exchange rate to be effective. We can identify two external effects. First, given the higher disposable incomes that the Job Guarantee workers would have compared to if they were unemployed imports would likely rise.

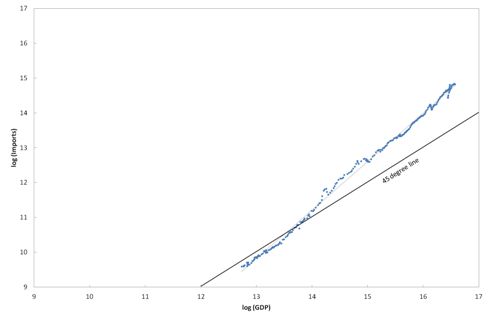

With a flexible exchange rate, the increase in imports would promote depreciation in the exchange rate. We should expect the current account to improve and net exports increase their contribution to local employment. The result depends on the estimates of the export and import price elasticities. The body of evidence available suggests that import elasticities are small (around –0.5).

This is a typical oversimplistic and incorrect approach.

First, Mitchell incorrectly claims that import elasticities are low for Australia citing a “body of evidence”. The number he quotes is price elasticity. He hides away from income elasticity. I suppose he thinks that the numbers estimated are “low” enough not worthy of mention. Unfortunately it is not.

Second, he claims that as a result of running an employer of the last resort by the government, the Australian exchange rate would fall and this would actually lead to an improvement of the current account.

This is a primitive neoclassical argument. While it is true that a depreciation of the Australian dollar would act to reduce imports due to price effects, it is no guarantee to reduce the trade imbalance. This is because if incomes rise faster, the trade imbalance may be rising (i.e., imports are rising) even if the Australian dollar is depreciating. Note that is different from the J-curve effect. Exports on the other hand depend on the competitiveness of Australian producers and demand conditions in the rest of the world and hence improvement of exports is dependent on how the rest of the world grows which cannot be assumed arbitrarily.

[Incidentally, producers in other nations may be even less competitive than Australian producers – thereby implying a stronger constraint on those nations because exports may not be rising as fast]

Funnily, the blog posts claims in one place that imports reduce and later that it increases. In that discussion, Mitchell seems to be addressing imported inflation – a somewhat less important detail here in this post.

Third and the most important point is since the exchange rate is not under official control, there is no guarantee that the exchange rate will depreciate. It may appreciate and stay at appreciated levels for an uncertain period till the net indebtedness of Australia rises to alarming levels.

I suppose Mitchell believes there cannot be a crisis because according to a 2008 paper coauthored by him, There is no financial crisis so deep that cannot be dealt with by public spending. Ironically during the global financial crisis which started in 2007-8, Australian banks went into a heavy US dollar funding problem which had to be resolved by the Reserve Bank of Australia using its credit lines at the Federal Reserve (via swap lines). This puts his huge claim that crises can simply be solved by public spending into pieces.

Now, if incomes rise in Australia, this has the adverse effect of deteriorating the balance of payments which Mitchell denies reguarly. Of course in real life, Australian authorities won’t like a deterioration. Here is where the fake trade-off of the employer of the last resort proposal comes in.

If incomes are to not rise because imports have to be kept under check, then the ELR is simply a redistribution to the ELR employee out of taxes. This is because more people receive the disposable income due to production and if output is constrained from the external sector, so are incomes – thereby implying lower disposable incomes for others already employed and not in the ELR.

Incidentally I mention in the passing that Australian banks are subject to vulnerabilities due to funding from foreigners – something Chartalists (who are also Minskyians) would deny. The huge amount of external funding needs of Australian banks – both in domestic and foreign currencies is a direct result of the current account imbalances accumulated over the past.

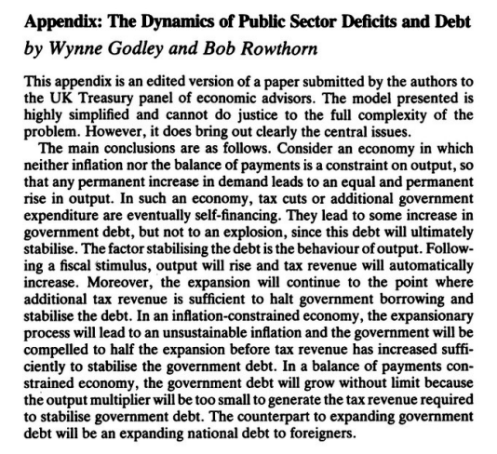

Somehow a group of Keynesians think that simply deficit spending solves all our problems.