In my previous post on government defaults and its connection to open economies, I had a comment from Sergio Cesaratto (who is full professor of Economics at the University of Siena (Italy)) which I liked. Since I don’t publish comments, I asked him if I could promote it to a post and he sent me an updated version which looks more like a post.

Sergio Cesaratto*

sergio.cesaratto@unisi.it

http://www.econ-pol.unisi.it/cesaratto/

http://politicaeconomiablog.blogspot.com/

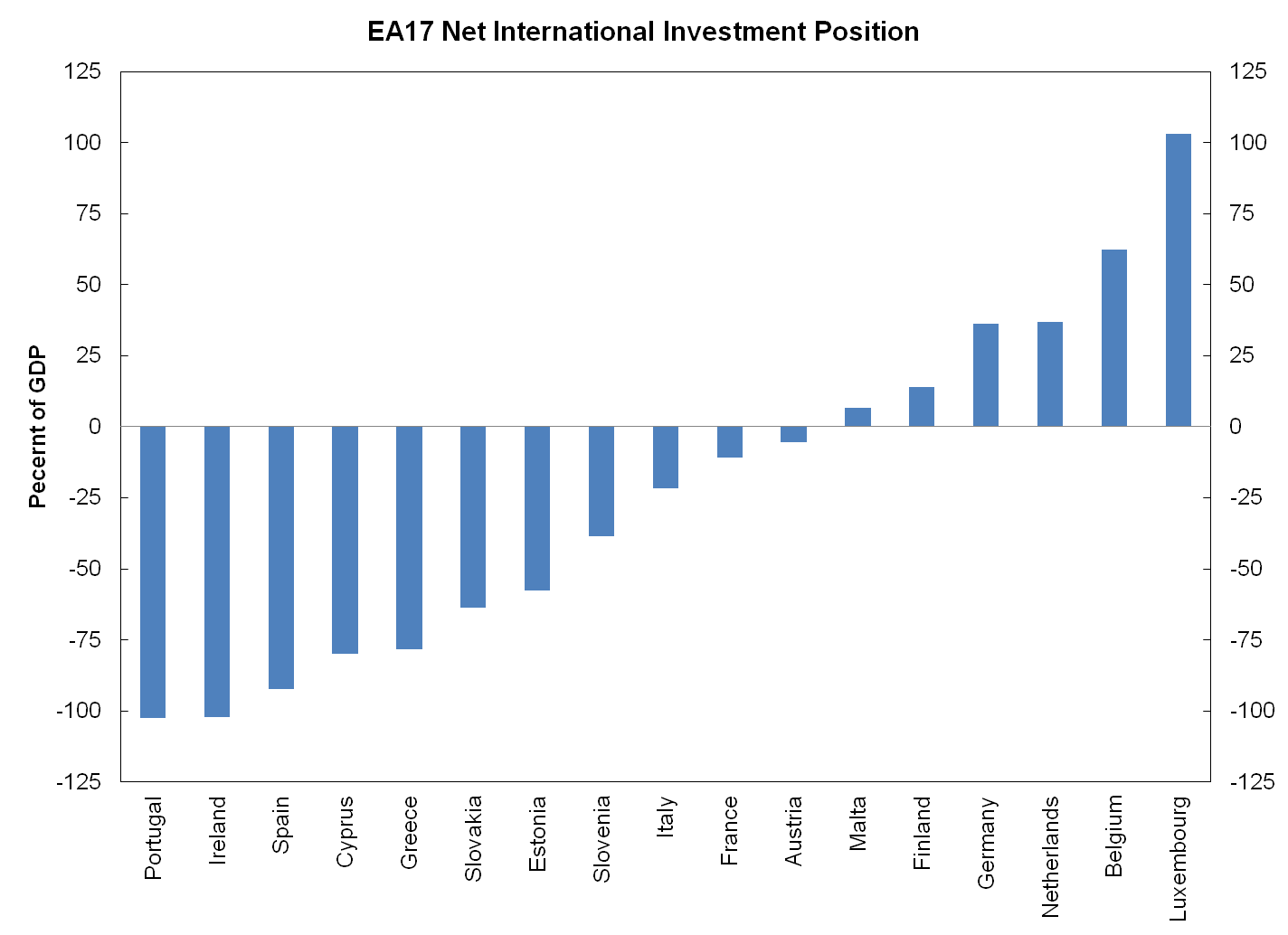

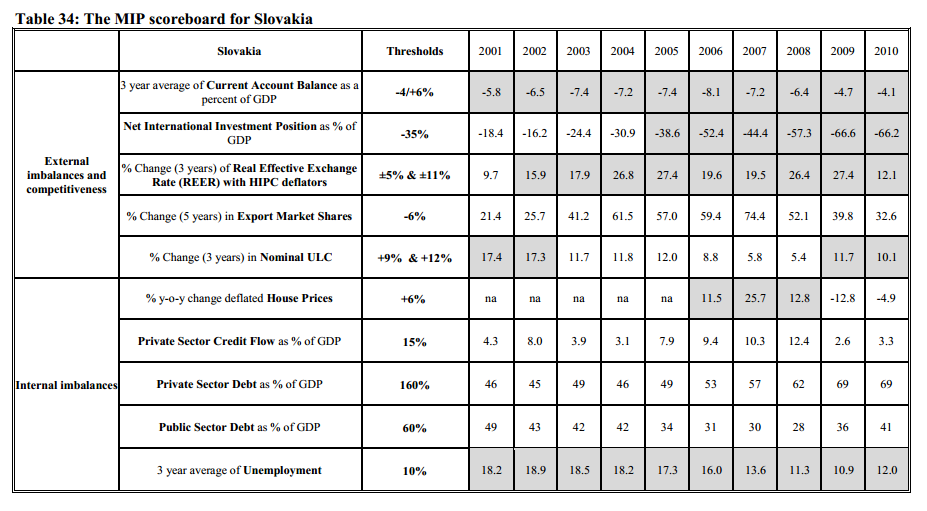

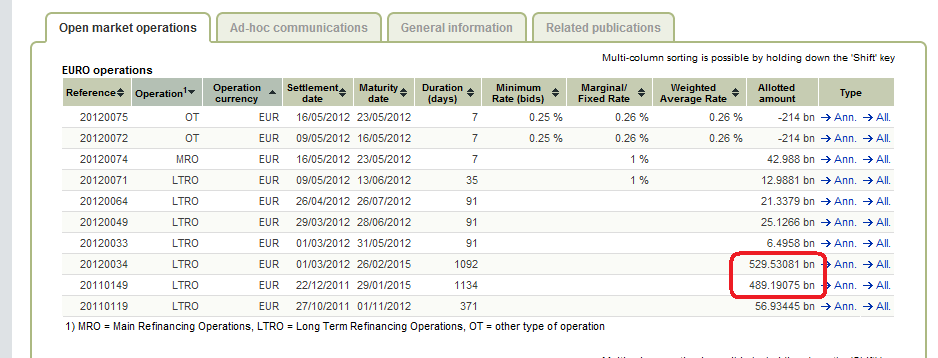

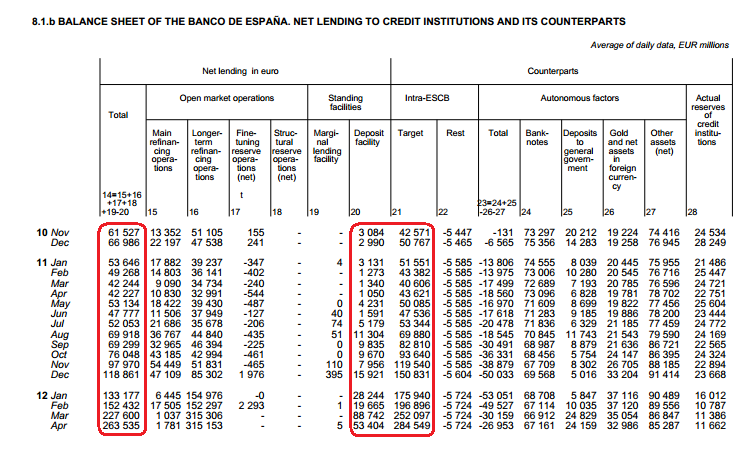

The absence of a truly European central bank to guarantee the liquidity of the European sovereign debts aggravated (although it not originated) the crisis by letting the sovereign spreads to spiralling upward. As consequence of the ECB deficient conduct, according to De Grauwe (2011: 8-10) the periphery’s public debts (PD) moved from a low risk to a high risk equilibrium, in his view from a liquidity to a solvability crisis. This is not totally correct since the original troubles with the European periphery seem solvability, not of just of liquidity, and indeed it emerged when liquidity was abundant and the sovereign spreads low. According to Wray and his MMT fellows this abundance just delayed the redde rationem of the deficient Eurozone (EZ) monetary constitution, so that they attribute an almost exclusive relevance to the renunciation to national sovereign central bank (SCB) as the explanation of the European financial crisis.

In short Wray argues that as long as a country retains a sovereign currency, that is it retain the privilege to make payments by issuing its own currency and does not promise to redeem the debt at any fixed exchange rate or worse in a foreign currency, then it cannot default and the nationality of the debt holders is irrelevant:

The important variable for them [Reinhart and Rogoff 2009] is who holds the government’s debt—internal or external creditors—and the relative power of these constituencies is supposed to be an important factor in government’s decision to default (…). This would also correlate to whether the nation was a net importer or exporter. We believe that it is more useful to categorize government debt according to the currency in which it is denominated and according to the exchange rate regime adopted. … we believe that the “sovereign debt” issued by a country that adopts its own floating rate, nonconvertible (no promise to convert to metal or foreign currency at a pegged rate) currency does not face default risk. Again, we call this a sovereign currency, issued by a sovereign government. …A sovereign government services its debt—whether held by foreigners or domestically—in exactly one way: by crediting bank accounts. … [it is indeed] irrelevant for matters of solvency and interest rates whether there are takers for government bonds and whether the bonds are owned by domestic citizens or foreigners. (Nersisyan and Wray 2010: 12-14).

While it is certainly right that if a fixed exchange rate leads to a current account (CA) deficit, a country is exposed to “sudden stops” in capital flows and the higher interest rate necessary to avoid the capital flights and to keep the parity will worsen the external and domestic imbalances Wray seems to hold a different view: for him the CA imbalances are irrelevant:

a country can run a current account deficit so long as the rest of the world wants to accumulate its IOUs. The country’s capital account surplus “balances” its current account deficit…. We can even view the current account deficit as resulting from a rest of world desire to accumulate net savings in the form of claims on the country.

That is, any country with a fully sovereign currency and no promise of convertibility at a given exchange rate can confide on an unlimited foreign credit. But for most of the countries countries, the no-promise of convertibility at a given exchange rate is precisely the case in which they will not get (cheap) foreign credit. Indeed, it is by promising at-pair convertibility that periphery countries can finance in a cheap way their CA deficits. This will, of course, often create future problems, but certainly a floating exchange rate would discourage cheap foreign lending. One may also say that a competitive (real) exchange rate policy is what periphery countries need, a position largely shared by development economists nowadays, not least because it is not conducive to a fictitious foreign-borrowing-led growth.

Wray (2001) elsewhere admits that the irrelevance proposition that any State

can run budget deficits that help to fuel current account deficits without worry about government or national insolvency

applies indeed only to the US: precisely because the rest of the world wants Dollars. But surely that cannot be true of any other nation. Today, the US Dollar is the international reserve currency—making the US special. … the two main reasons why the US can run persistent current account deficits are: a) virtually all its foreign-held debt is in Dollars; and b) external demand for Dollar-denominated assets is high—for a variety of reasons.

The main reason seems that the U.S. issues the main reserve currency and you issue a liability (so to speak, it’s fiat money) internationally fully accepted even without a commitment to convert it in something else. So, what Wray say, with a sovereign currency PD and CA debts are not a problem only apply to the U.S.

With fixed exchange rates, it is not so much the promise to redeem the debt at a fixed exchange rate or in a foreign currency that creates problems. It would not be a problem in CA surplus countries, for instance. The problem is that fixed exchange rates lead periphery countries to a CA deficit, to the fear of devaluation, unsustainable interest rates, “sudden capital stops” etc. Recall that the European unbalances initially grew with a ECB pursuing very low interest rates that with financial liberalization and the end of a devaluation risk led to the bubbles in the periphery and eventually to the unbalances. This is not to say that the role of a SCB is not relevant: quite the opposite. Lately, the ECB should and could have operated to avoid the increase in the sovereign spread, but it could not have avoided the preceding sequence of events.

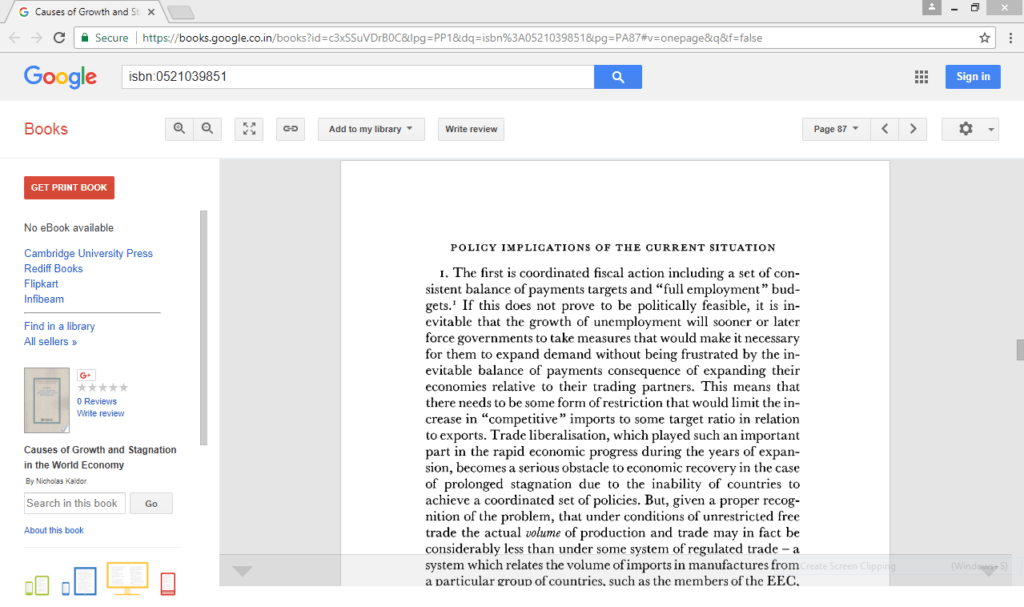

It may be added that with the right institutional setting, the EZ could be a perfect U.S.-MMT style country. With the full backing of the ECB the infra-European financial imbalances would be perfectly sustainable for a region with external balanced accounts that, what’s more, issues an international currency. The institutional change required for the EZ to resemble the U.S. includes the transfer of the conspicuous part of existing PDs along with many government budget functions to a federal government (to avoid moral hazard),[1] while national States would work as the American local States. Monetary policy should cooperate with fiscal policy to pursue full employment and, subordinated to this, price stability. Federal transfers from dynamic to troubled areas should dramatically increase while minimum standard welfare rights should be universally recognised to all European citizens. Labour mobility and infra-EZ direct investment should be incentivised. Actually, fiscal pacts were already includes in the Maastricht (1992) and Amsterdam (1997) treaties, in which the European periphery exchanged budget discipline with German inflation ‘credibility’ and low interest rates. As the subsequent experience has shown, the troubles have not derived from fiscal indiscipline. Part of the problems certainly derived from a deregulated finance. At the European and national level, financial resources should therefore be re-regulated to sustain public, social and environmental investment rather than construction or consumption bubbles. Public or semi-public investment banks should be used at both levels to this purpose. Be as it may, at the time of writing this project appear still too challenging for real Europe, a club of independent states. Short of this full institutional unification, a pro-active monetary and budget policies at the European level, particularly in the surplus countries, would of course also go into the direction of a solution.

References

De Grauwe Paul (2011) Managing a fragile Eurozone, Vox

Nersisyan Y., Wray R.L. (2010), Does Excessive Sovereign Debt Really Hurt Growth? A Critique of This Time Is Different, by Reinhart and Rogoff, Working Paper No. 603, Levy Institute June 2010

Wray L.R. (2011), Currency Solvency and the Special Case of the US Dollar

(this post is a section of a longer essay on the European crisis; I originally sent a summary to Concerted action as a comment to his latest post. I thank Ramanan for promoting it to a post and, without implications, Eladio Febrero for comments).

* Sergio Cesaratto is full professor of Economics at the University of Siena (Italy).

[1] As Nersisyan and Wray 2010: 16 argue:

With a sovereign currency, the need to balance the budget over some time period determined by the movements of celestial objects or over the course of a business cycle is a myth, an old-fashioned religion. When a country operates on a fiat monetary regime, debt and deficit limits and even bond issues for that matter are self-imposed, i.e., there are no financial constraints inherent in the fiat system that exist under a gold standard or fixed exchange rate regime. But that superstition is seen as necessary because if everyone realizes that government is not actually constrained by the necessity of balanced budgets, then it might spend ‘out of control,’ taking too large a percent of the nation’s resources.