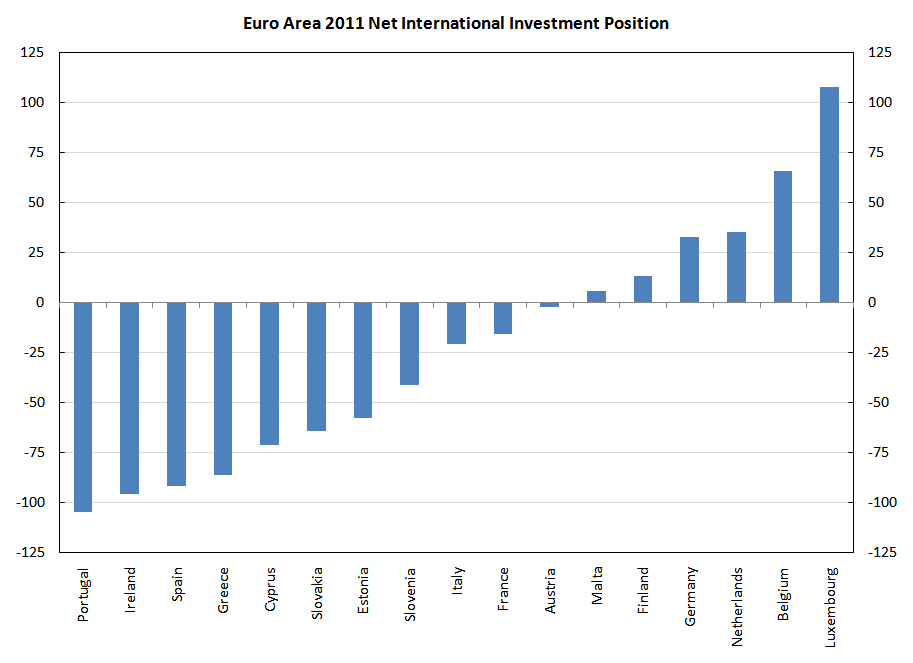

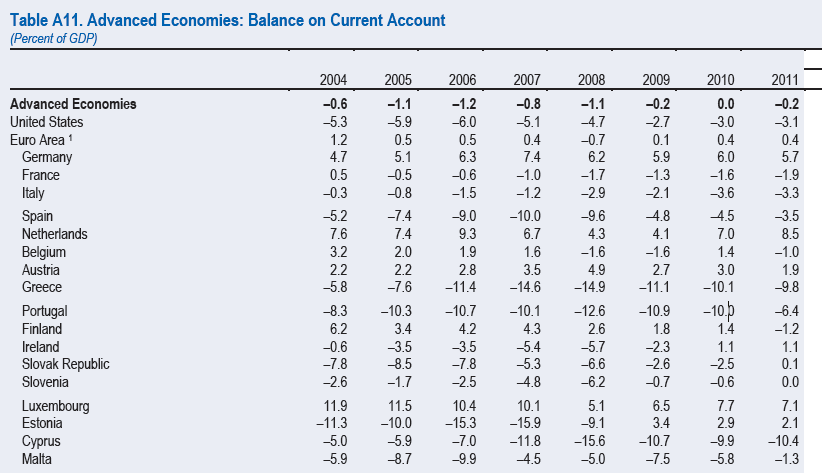

Over this thread at Matias Vernengo’s blog Naked Keynesianism, I got into an exchange about current account deficits and sustainability with an anonymous commenter – a topic I had blogged on recently in 2-3 posts.

The commenter seems to not understand how this works or seems to believe that net indebtedness cannot keep rising relative to GDP in scenarios. I will present some scenarios below. The scenario presented below is not what literally happens but rather shows the absurdity of some types of growth.

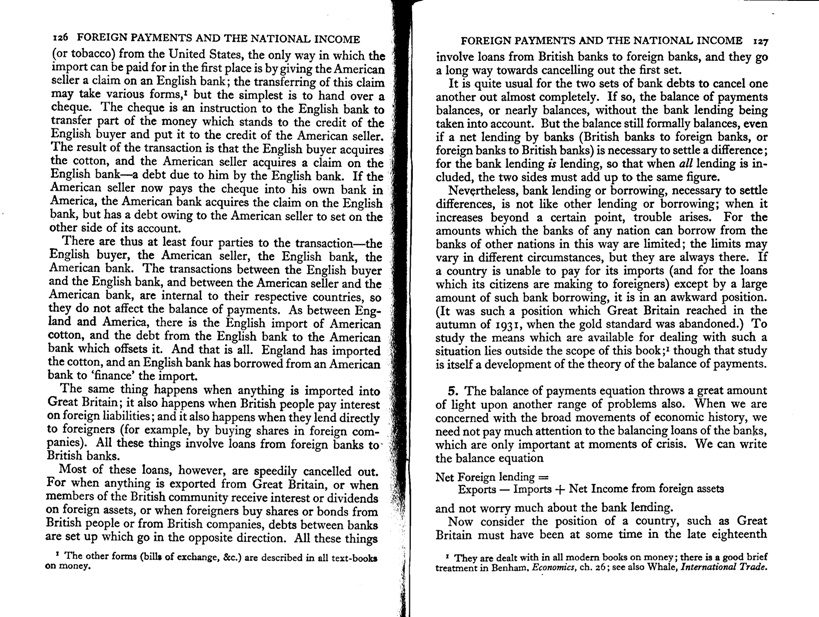

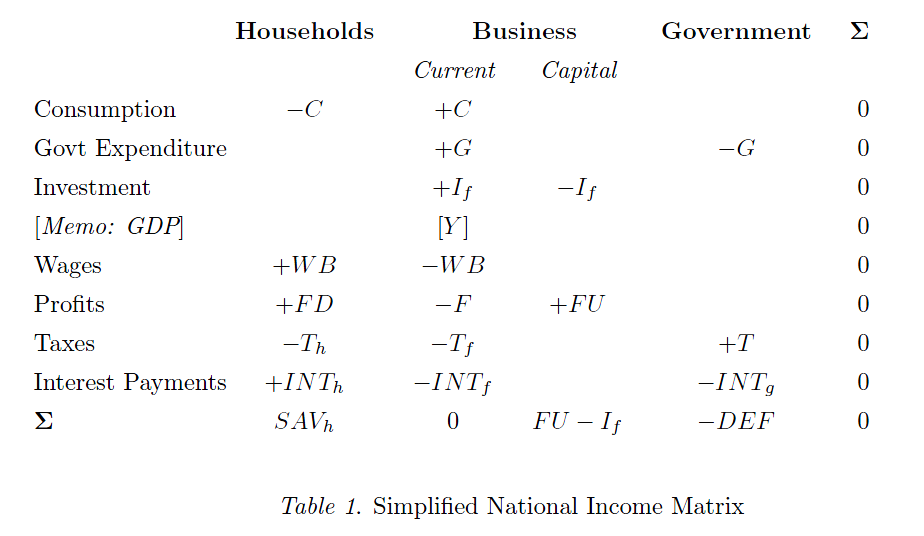

Before this, let me give the expression for net indebtedness to foreigners. Ignoring revaluations, only current account transactions change claims on foreigners or claims by foreigners on residents. So

Change in Net Indebtedness to Foreigners = Current Account Deficit.

For simplicity, I will ignore other items in the current account – such as interest and dividend payments between residents and non-residents etc.

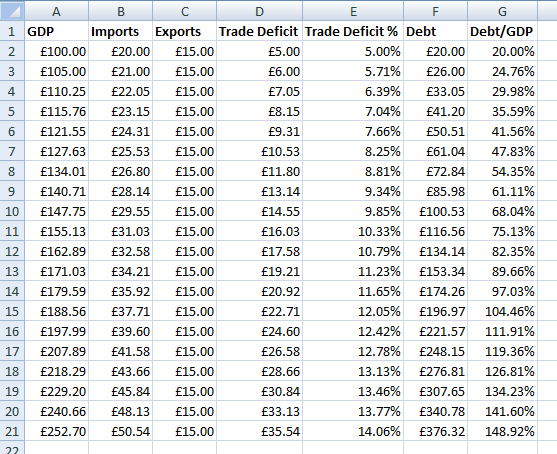

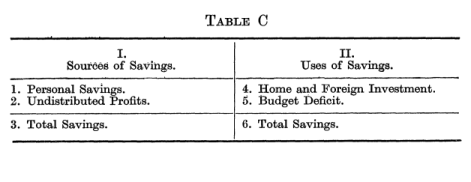

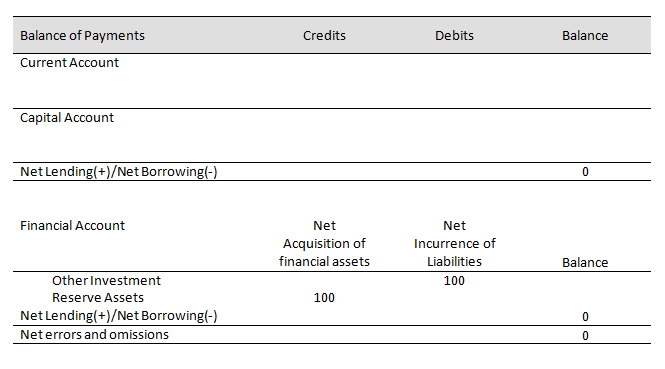

So start with GDP of £100, imports of £20 and exports of £15 and net indebtedness to foreigners of 20% of GDP.

Assume GDP grows at 5% annually. Imports as a percent of GDP is 20% and exports do not grow.

(In real life imports can be even worse when output changes but let’s just keep things simpler).

The numbers are nominal values.

So here is how it looks in Excel:

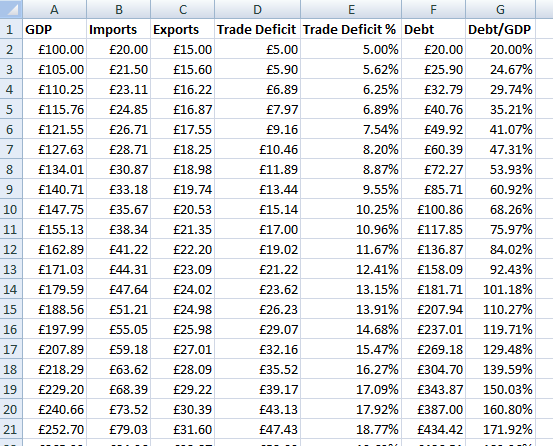

Now one can argue about the simplicity in the assumption that export was held constant. So here it is at 4% export growth.

To make it more realistic, I also use import elasticity of 1.5 – which means that for a 1% rise in GDP, imports rise by 1.5%.

Deteriorating in either case. If you were to extend the scenario to more rows in Excel, you can see how it rises forever.

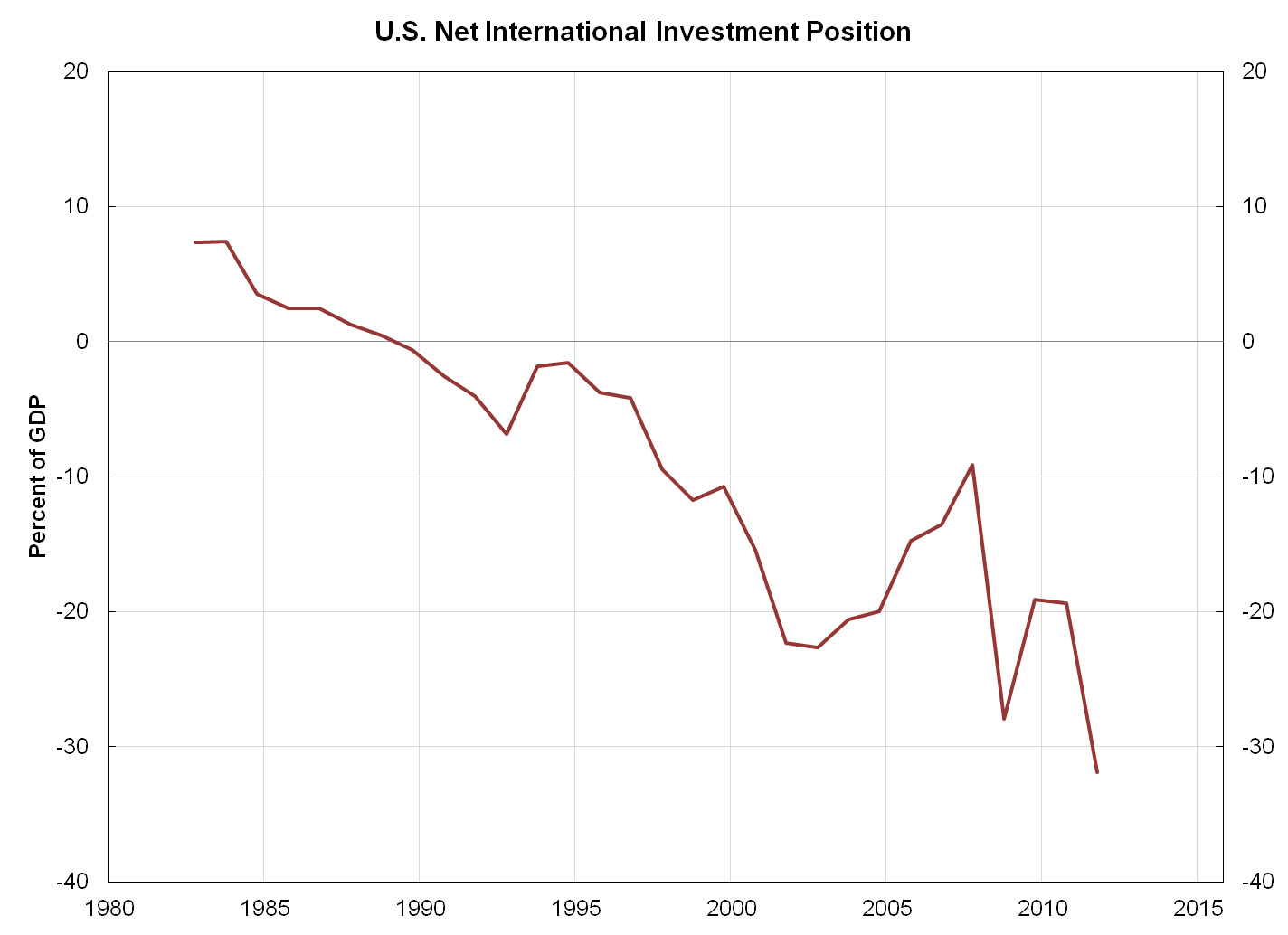

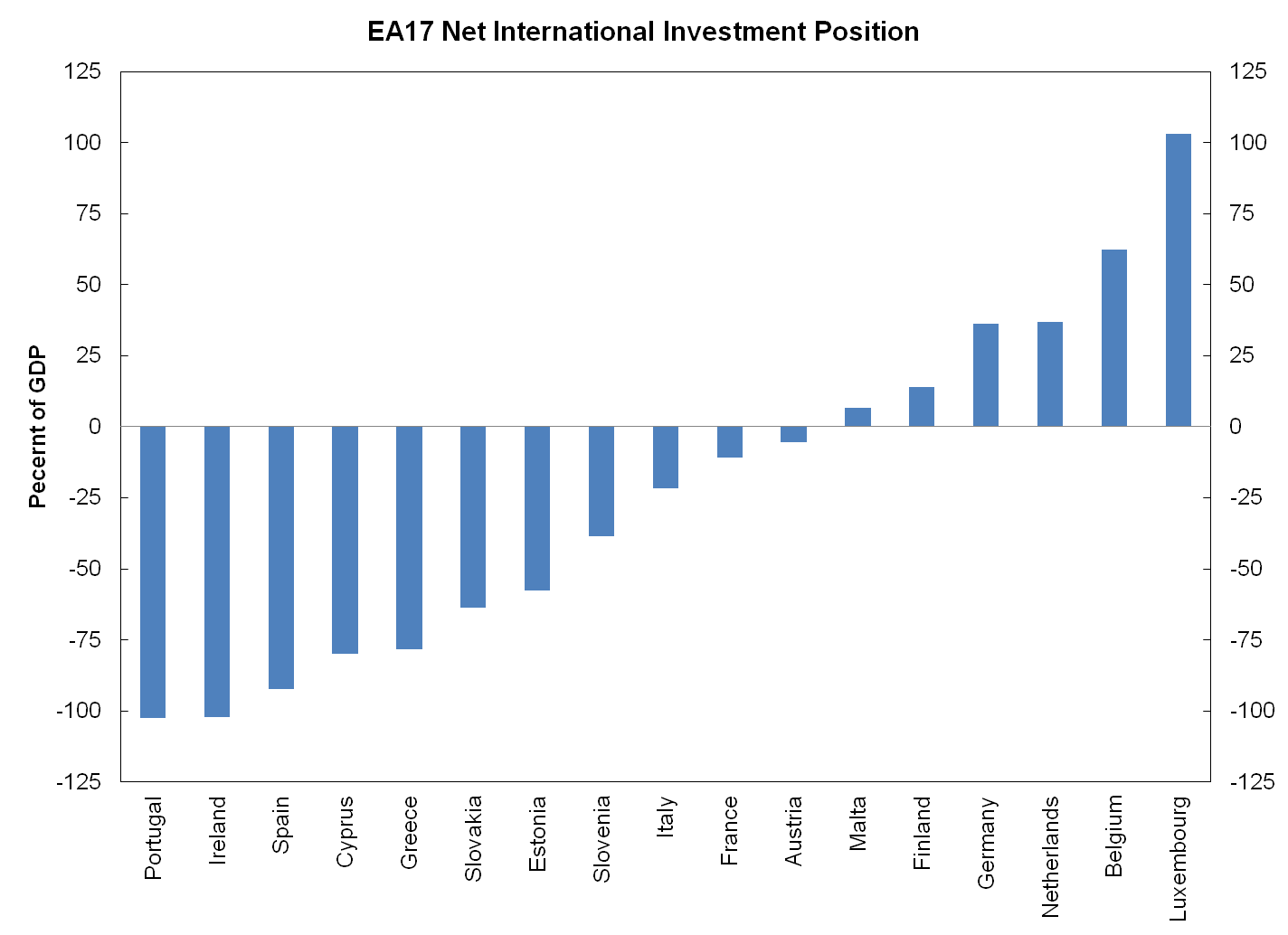

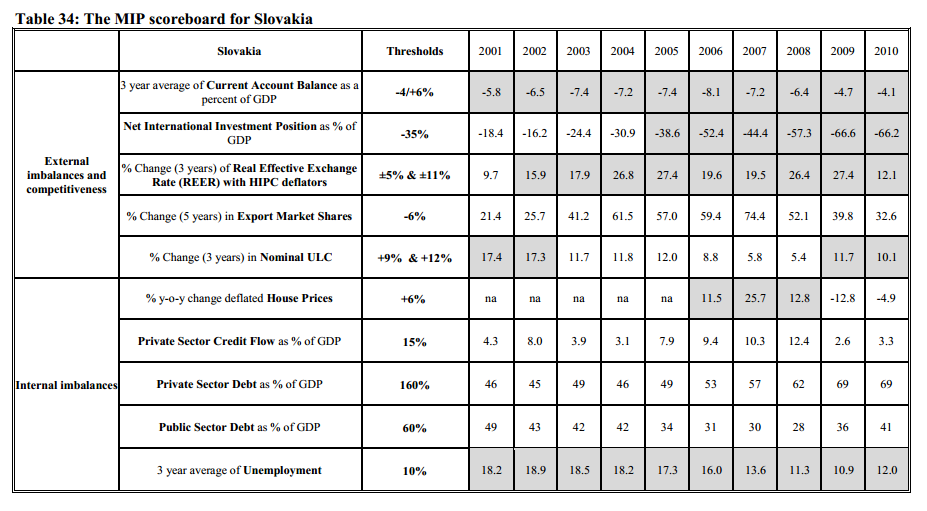

It illustrates one thing: At sufficiently low growth of exports or a high propensity to import, a faster rate of growth of output comes with net indebtedness to foreigners rising relative to GDP which cannot be sustained for long.

Also if one assumes (although not always the case) that the private sector net accumulation of financial assets (NAFA) is a small positive number (such as 2% of GDP), then the current account reflects directly on the fiscal deficit because of the sectoral balances identity.

You can do this on your own sheet and see how these numbers change for different scenarios assumed.

The reason I have a numerical example is that it is easier to see how fast these stocks and flows change.

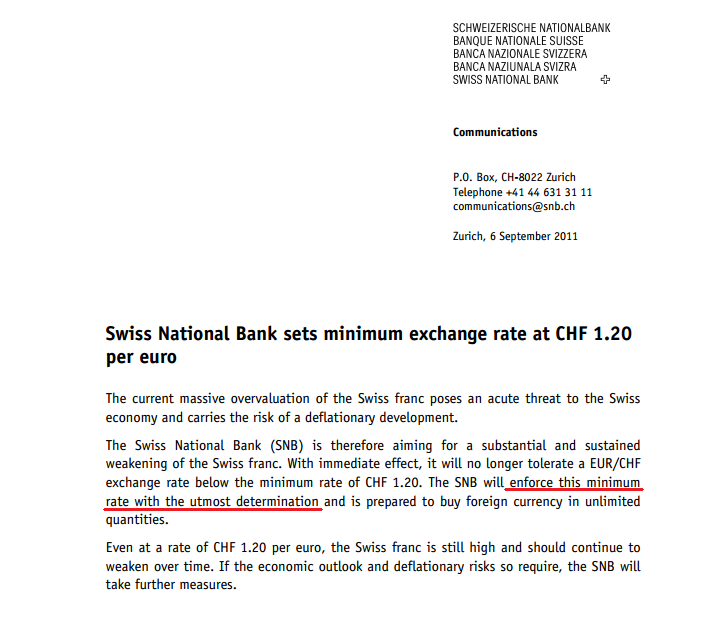

This example is an illustration of the balance-of-payments constraint nations face. Faced with rising current account imbalances, nations may be faced with little optimism – such as the ability to use of fiscal policy to improve demand and output. In a world of free trade, there is less one can do such as raising tariffs, import controls and so on. The trend in international political economy is actually tending toward reducing tariffs which makes the problem even worse. Subsidies to exporters can be provided but these lead to cries of foul at WTO. Even if subsidies are given to exporters, they are limited by how well they can compete with big firms in international markets. When this happens for everyone – such as at present – an international political economy game happens where muddled policy makers try to discuss something but in the end vow to continue free trade policies. Or they play games such as beggar-my-neighbour. Whatever said, a nation’s success crucially depends on how their producers do in international markets.

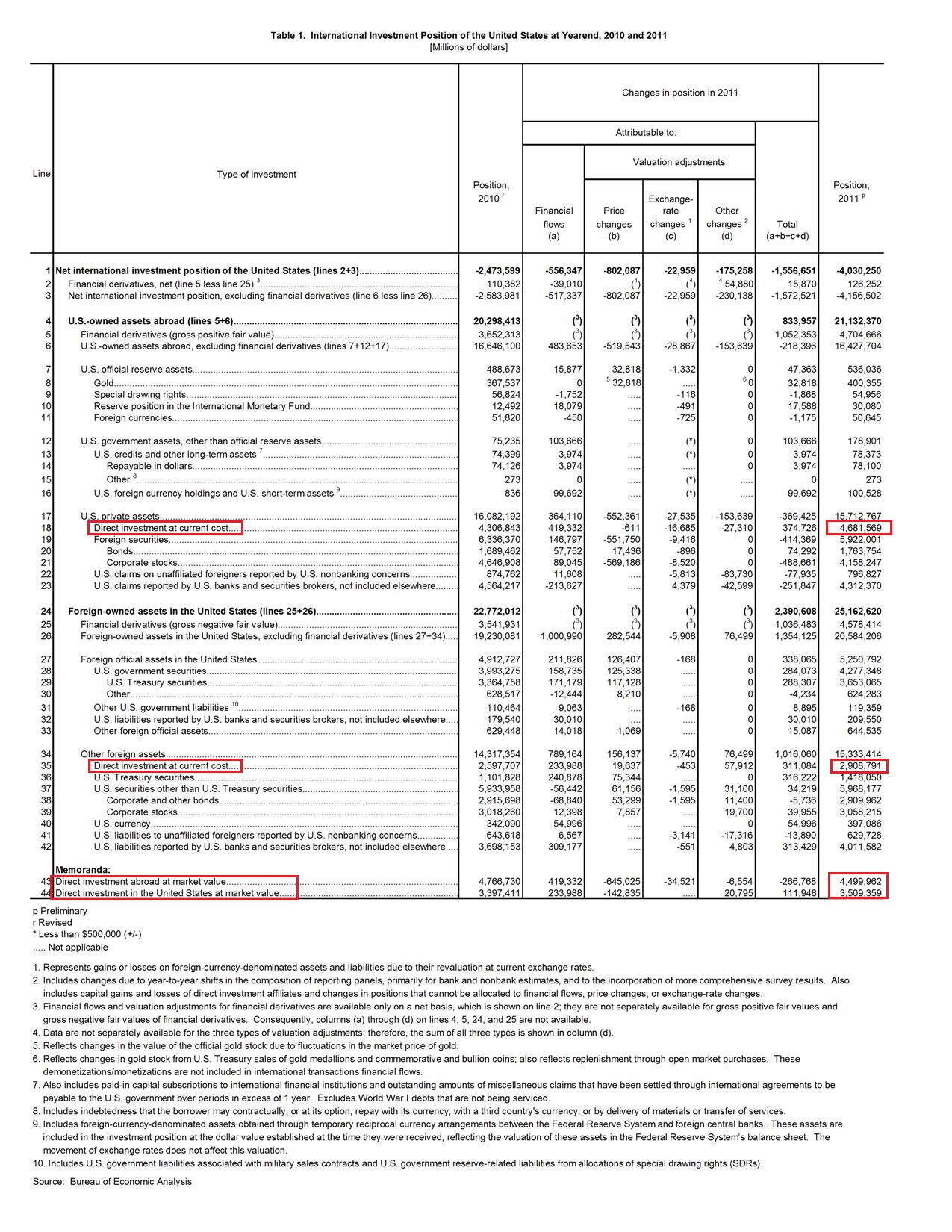

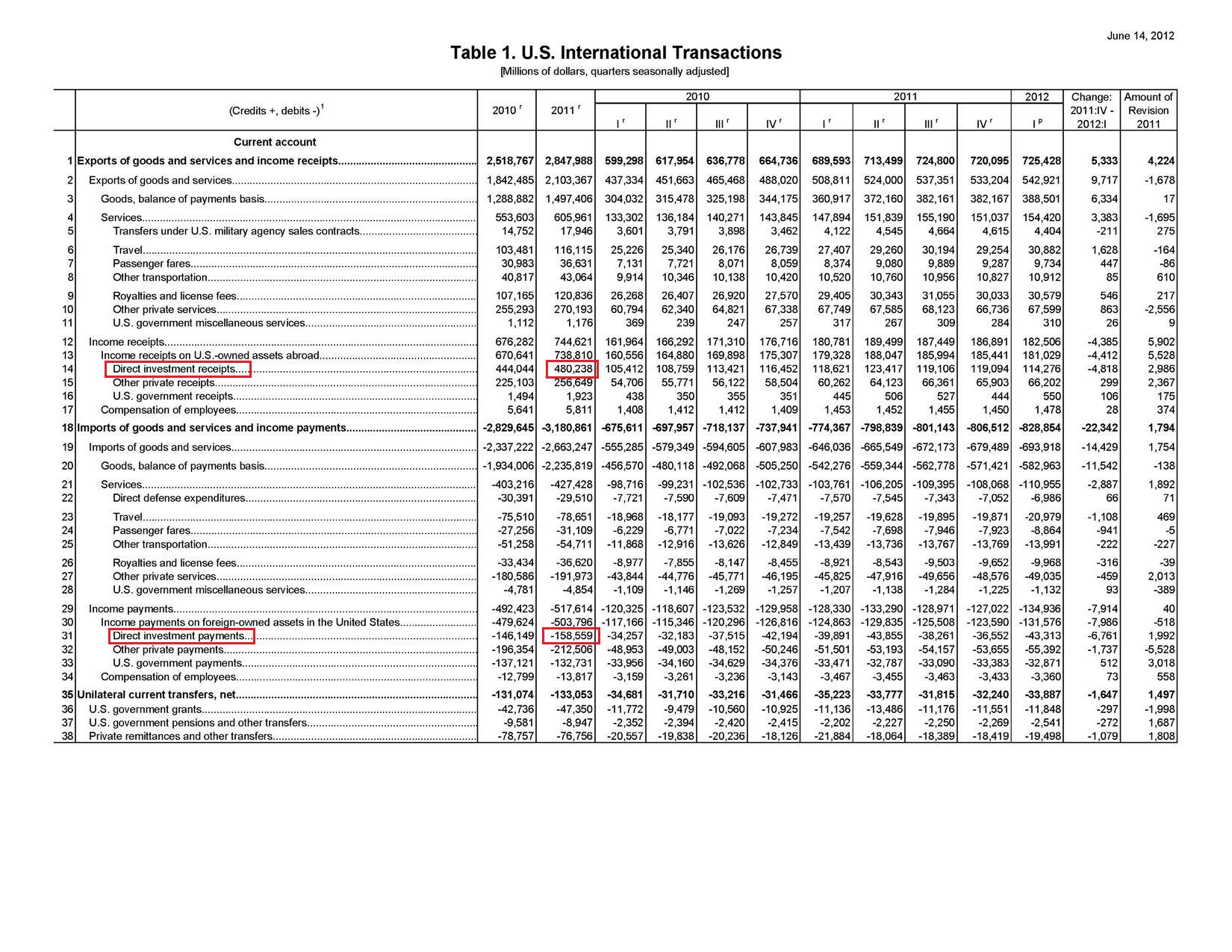

Back to stocks and flows. In real life things get more complicated and interesting. A nation may receive a lot of payments from abroad – even if its trade balance is worsening because of direct investments made in the past etc. Residents hold stock market securities abroad and these may make a killing – so analysing this becomes even more interesting! So high holding gains of assets held abroad may be sufficient to prevent net indebtedness from rising even if the current account balance is high. So there is an interesting dynamics here but finally, the current account balance wins over revaluations.

The example is motivated by one given in Wynne Godley and Francis Cripps’ book Macroeconomics.