Louis-Philippe Rochon — The Economics Of Basil Moore

Good talk by LPR on the evolution of Basil Moore’s views on endogenous money. Talk presented at the ‘International Symposium on Economic Thought’ conference, November 28th, 2020.

Louis-Philippe Rochon — The Economics Of Basil Moore

Good talk by LPR on the evolution of Basil Moore’s views on endogenous money. Talk presented at the ‘International Symposium on Economic Thought’ conference, November 28th, 2020.

Basil Moore passed away recently, as I mentioned a few days back in this blog.

One of the criticisms of Moore’s work was the passive role of banks. Louis-Philippe Rochon has an excellent article in his Festschrift Complexity, Endogenous Money and Macroeconomic Theory — Essays in Honour Of Basil J. Moore, Edward Elgar, 2006, to further develop Moore’s views.

Below is the scan of the full article, provided to me by LP for posting here.

The object below is an embed of the pdf. If the embed doesn’t display, or to get a better view, you can open it in a separate browser tab here.

Basil Moore passed away yesterday. 💐

Post-Keynesian economics greatly influenced Post-Keynesian monetary theory. Although his work was present in Cambridge Keynesians work, such as Joan Robinson, Nicholas Kaldor, Wynne Godley and Francis Cripps, they didn’t influence the thinking on monetary matters as much as Moore did with his great book Horizontalists And Verticalists — The Macroeconomics Of Credit Money.

He does recognise Kaldor’s work in that book:

The obvious lesson to be learned from the experience with the General Theory in the past fifty years is that .. revolutionizing the way the world thinks about economic problems” is an enormously difficult task. In spite of the mountains of Keynesian exegesis that has been produced, Nicholas Kaldor was the sole English-speaking economist of the first rank to have endorsed what is here termed the Horizontalist position (1970, 1981, 1982, 1983, 1985a, b). This book represents my attempt to enlist the support of other scholars in what has at times seemed a quixotic crusade by a member of the lunatic fringe against the prevailing orthodoxy.

I regret not having met him. My only interaction was to ask him via email, where I can buy his book Horizontalists And Verticalists because it cost $450 on Amazon at the time! He didn’t know but replied recommending his book Shaking the Invisible Hand: Complexity, Endogenous Money and Exogenous Interest Rates. But later I managed to get the book. He also said that

It was my attempt to introduce endogenous money into the Macro literature, but no one has heard of it since the mainstream never reviewed it. (They gave H&V to Phil Kagan, a leading Monetarist, who didn’t much like it, but at least it was reviewed.

Noechartalists will be surprised to know that Moore also endorsed Chartalism in his 1988 book:

[page 8] Soft or fiat money refers to unbacked paper or token coins. It maintains its value because it is legally tenderable (by fiat) in settlement of debts and taxes.

…

[page 18] Currency (fiat money) is the physical embodiment of the n,onetary unit of account (numeraire) defined by the sovereign government. It is a sure and perfectly liquid store of value in units of account. It is legal tender for the payment of taxes and for the discharge of private debt obligations enforceable in courts of law. In consequence it is generally accepted as a means of payment.

…

[page 294] Money of any kind allows the breaking of the barter quid pro quo that is imposed by lack of trust and for which money is not a substitute. Even though intrinsically worthless, money is acceptable to me provided that it is also acceptable to you and to everyone else. Trust in money now comes from government guarantee of its acceptability as legal tender. “Today all civilized money is beyond the possibility of dispute, chartalist” (JMK, 5, p. 4).

…

[page 372] Fiat money represents a bridge between the world of commodity money and credit money. In its liquidity characteristics it is virtually identical to commodity money, except that it is chartalist.

There were many places I disagreed with Moore. I don’t think he was a fan of the use of expansionary fiscal policy. I don’t know why he claimed that the Keynesian multiplier doesn’t exist. But as Geoff Harcourt says in the foreword to the book Complexity, Endogenous Money and Macroeconomic Theory — Essays in Honour Of Basil J. Moore:

But, important as these contributions have been, Basil has influenced many other topics, sometimes by his innovative thinking, sometimes by being the irritant that has led other oysters to create pearls of their own. Especially is this true of his highly individual approach to the true meaning of the Keynes–Kahn–Meade multiplier concept and also to the validity of Keynes’s concept of effective demand as presented in The General Theory. Basil has made us think anew about our understanding of the natures of saving and investment, their relationship to each other, to the concept of an under-employment rest state, and also of the relationship of the macroeconomic income and expenditure accounts, balance sheets and funds statements to the behavioral relationships originally developed by Keynes and his followers. To sometimes disagree with Basil’s arguments is not at all to detract from the great stimulus he has provided for fundamental rethinks of basic, central, core concepts and relationships.

Post-Keynesian Economics has lost a giant. R.I.P., Basil Moore.

I am not. But the post is about the possibility. The title is borrowed from a paper by Gérard Duménil and Dominique Lévy.

Steve Roth has an article titled Note To Economists: Saving Doesn’t Create Savings. If you follow his blog regularly, his pieces read

The definition of saving is wrong. Saving is equal to income minus expenditure.

That’s not an exaggeration. He actually says it:

… Since saving = income – expenditures, [aggregate] saving must equal zero.

Steve Keen on Twitter supports Steve Roth.

click to view the tweet on Twitter

What’s with economists’ dislike for national accounts?

Steve Roth uses the phrase “savings” as a stock. Obviously his claim is just wrong as we know from national accounts:

Change in net worth = Saving + Holding Gains.

(with netting in holding gains).

Steve Keen doesn’t use saving as a stock but as a flow and a plural of saving. But Steve Keen’s point is also wrong. National saving is equal to the sum of saving of all economic units, such as households, firms, government etc. Even the household sector’s propensity to save collectively matters. That’s what macroeconomics is all about.

Now moving the more important point: is it possible that a higher propensity to consume reduces the long run rate of accumulation?

There are several Post-Keynesian economists who have considered the possibility. Of course it should be contrasted with supply side neoclassical economics. A few are Basil Moore, Wynne Godley, Marc Lavoie, and Gérard Duménil and Dominique Lévy as mentioned at the beginning of this post.

In their paper Kaleckian Models of Growth in a Coherent Stock-Flow Monetary Framework: A Kaldorian View, Godley and Lavoie find this in their models (draft version here):

We quickly discovered that the model could be run on the basis of two stable regimes. In the first regime, the investment function reacts less to a change in the valuation ratio-Tobin’s q ratio-than it does to a change in the rate of utilization. In the second regime, the coefficient of the q ratio in the investment function is larger than that of the rate of utilization (γ3 > γ4). The two regimes yield a large number of identical results, but when these results differ, the results of the first regime seem more intuitively acceptable than those of the second regime. For this reason, we shall call the first regime a normal regime, whereas the second regime will be known as the puzzling regime. The first regime also seems to be more in line with the empirical results of Ndikumana (1999) and Semmler and Franke (1996), who find very small values for the coefficient of the q ratio in their investment functions, that is, their empirical results are more in line with the investment coefficients underlying the normal regime.

… In the puzzling regime, the paradox of savings does not hold. The faster rate of accumulation initially encountered is followed by a floundering rate, due to the strong negative effect of the falling q ratio on the investment function. The turnaround in the investment sector also leads to a turnaround in the rate of utilization of capacity. All of this leads to a new steady-state rate of accumulation, which is lower than the rate existing just before the propensity to consume was increased. Thus, in the puzzling regime, although the economy follows Keynesian or Kaleckian behavior in the short-period, long-period results are in line with those obtained in classical models or in neoclassical models of endogenous growth: the higher propensity to consume is associated with a slower rate of accumulation in the steady state. In the puzzling regime, by refusing to save, households have the ability over the long period to undo the short-period investment decisions of entrepreneurs (Moore, 1973). On the basis of the puzzling regime, it would thus be right to say, as Dumenil and Levy (1999) claim, that one can be a Keynesian in the short period, but that one must hold classical views in the long period.

So there is a possibility that a higher propensity to consume leads to a lower growth in the long run. I do not think this is generally true, but this could be possible in some economies.

Two conclusions. It’s counter-productive to mix the definition of saving and what’s called “net lending” in national accounts. It’s possible (which shouldn’t mean that it’s necessarily the case) that Keynes’ paradox of savings doesn’t hold in the long run. I don’t believe that’s the case but purely arguing using national accounts and/or changing definitions won’t do.

The world is more Kaldorian than Keynesian. After the crisis, Keynes became popular again but his Cambridge descendent Nicholas Kaldor is hardly remembered by the economics community. Even his biographers have some memory loss of him.

Anthony Thirlwall and John E. King are biographers of Nicholas Kaldor. Superb books.

There’s a chapter Talking About Kaldor: An Interview With John King in Anthony Thirlwall’s book Essays on Keynesian and Kaldorian Economics. There’s an interesting discussion on money endogeneity (Google Books link):

J.E.K. … I wonder if Kaldor would have gone as far as Moore in arguing that the money supply curve is horizontal.

Anthony Thirlwall replies saying he would have argued that the supply of money is elastic with respect to demand, instead of quoting him. Here’s Nicholas Kaldor stating explicitly in a footnote in Keynesian Economics After Fifty Years, in the book, Keynes And The Modern World, ed. George David Norman Worswick and James Anthony Trevithick, Cambridge University Press, 1983, on page 36:

Diagrammatically, the difference in the presentation of the supply and demand for money, is that in the original version, (with M exogenous) the supply of money is represented by a vertical line, in the new version by a horizontal line, or a set of horizontal lines, representing different stances of monetary policy.

[italics: mine]

Anthony Thirlwall is one of the commenter in the book chapter. The book is proceedings of a conference on Keynes.

But that’s not enough. Turn to page 363 of the book.

A.P.T. He had a very high regard for Sraffa but he never wrote on this topic.

J.E.K. Not something that would really have concerned him very much? Too abstract and too removed from reality?

A.P.T. Probably, yes. It is quite interesting that Sraffa was his closest friend, both personal and intellectual, and they used to meet very regularly – almost every day when Sraffa was alive. But there’s no evidence that they ever discussed Production of Commodities by Means of Commodities.

J.E.K. That’s amazing. There’s certainly no evidence that he ever wrote anything on those questions.

A.P.T. There’s no evidence that he wrote anything, or that indeed he really understood Sraffa. Well, he had the broad thrust, but I don’t know that he ever read it carefully, or understood the implications.

In Volume 9, of Kaldor’s Collected Works, there are two memoirs. One of Piero Sraffa and the other on John von Neumann.

Nicholas Kaldor on Piero Sraffa

Interestingly the editors and F. Targetti (another biographer) and A.P. Thirlwall!

I guess if you know a person so closely – like the biographers do, of Kaldor- you tend to forget a few things about them.

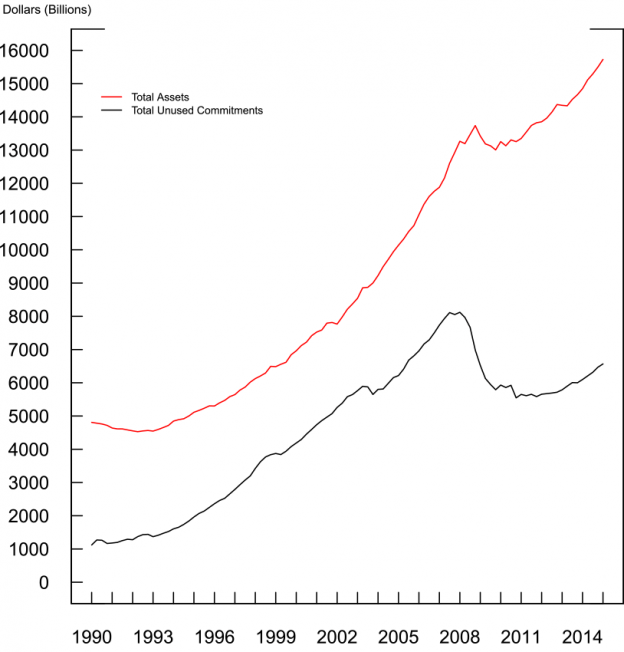

The Federal Reserve produces quarterly data for the financial accounts of the United States (earlier called “flow of funds”). There are a few notable additions termed enhanced financial accounts, which are in the process of being added. Some additions are details about money market mutual funds, off-balance sheet items of depository institutions, such as unused commitments, letters of credit and derivatives. This is the chart from the Federal Reserve’s FEDS note Off-Balance Sheet Items of Depository Institutions in the Enhanced Financial Accounts

Moore has a sophisticated way of saying things (pages 24-25):

In making a loan commitment a bank should be viewed as a participant in forward rather than spot lending markets. Viewed as a seller of contingent claims, banks themselves obviously can excercise only limited control over the volume of their lending.

On page 186 of Moore’s book, he also notes that Keynes talks about this in his book A Treatise On Money:

Keynes insists that cash facilities of the public includes unused overdraft facilities, “of which we have no statistical record whatever” (JMK, 5, p. 37). He then concludes, “Thus the cash facilities, which are truly cash for the purposes of the theory of the value of money, by no means correspond to the bank deposits which are published” (JMK, 5, p. 38).

Tracking Keynes’ writing Moore concludes that although Keynes talked of unused overdraft facilities, he fails to recognize its importance in theory. Moore says (p. 203):

Keynes then returned to the issue of unused overdraft facilities, without, however, recognizing that this was the key to the endogeneity of the money stock:

[Keynes]: In Great Britain the banks pay great attention to the amount of their outstanding loans and deposits, but not to the amount of their customers’ overdraft faclities … it means that there is no effective pressure on the resources of the banking system until the finance is employed … there is no superimposed pressure resulting for planned activity over and above the pressure resulting from actual activity. (JMK, 14, pp. 222-23).

Honestly, I am not sure what Keynes is trying to say in all this. Moore is quite clear in his book. It’s still nice to know that Keynes discussed all this. Perhaps he wanted to say something more but couldn’t translate his thoughts in words. But if you can interpret Keynes, do tell me!

What brings the supply and demand for money into equivalence?

It is interesting that the recent Bank of England quarterly bulletin referred to an article of Peter Howells, a Post-Keynesian (also available here), although I don’t think the authors appreciate why the paper is interesting.

The title of my blog post is flicked from a paper by Basil Moore which is in reply to Howells.

Howells sets up the problem:

[B]anks set up their collateral standard and lending rates … and then meet all loan requests forthcoming. The demand for loans is determined by other variables in the economic system … making the loan volume exogenous from the banks’ point of view and the resulting quantity of deposits endogenous … Notice, crucially that in this view, increases in the money supply are demand-determined but the demand in question is the demand for loans … the question then is what reconciles the demand resulting from this lending with peoples’ willingness to hold money? … What is it that ensures that the supply of new deposits created by the flow of net new lending is just equal to the quantity demanded?

Let me present it in another way. To be clear let us assume the economy is closed. Output is determined by domestic demand or by private expenditure and government expenditure. Output is equal to the national income and is distributed to various economic units such as households who among other things allocate a part of their wealth into deposits. So there is a money demand. Of course expenditure is partly from income and sale of existing assets and by borrowing from other economic units and in particular from banks which lend by creating deposits in this process. So there is a change in the money supply. So there are two pictures with overlapping stories but not exactly so the question is – what processes ensure that

Ms = Md

is valid at every instant of time?

Does the rise in income and higher demand for money (because of a rise in wealth) alone ensure this? Is there a price clearance? Prices of what? Goods and services? Or prices in financial markets? (‘price’ includes interest rates such as deposit rates, loan rates, bond yields, equity prices and so on).

Also note this is in nominal variables. So is the rise in income purely due to a rise in prices or purely a rise in real output or a mix of the two? What causes inflation?

Where does QE fit into this? Does it raise output? Real/nominal? Raise prices – of goods and services or asset prices or both?

It is important to appreciate the formulation of the question. In case you don’t yet appreciate the question, more from Howells:

The starting point is that the demand for the loans that create the deposits originates in the desire of deficit units to spend in exceess of income. It is a question of financing an income-expenditure discrepancy. Furthermore, it is a decision made by a subset of the community since not everyone is involved in demanding an increase in their indebtedness to banks. (Indeed it is not even the case that everyone holds a stock of bank debt…). By contrast, the decision to hold (i.e., not spend) the newly created deposits is a portfolio decision. Furthermore, it is a decision made by different people (“the community as a whole”) from those concerned with borrowing it… the fact remains that so long as we are dealing with two groups of agents, with different motives, an ex ante coincidence of preferences is quite implausible. The question, then, is how are these ex ante preferences to be reconciled, ex post.

Back to Moore’s paper. Moore summarizes possible solutions suggested by Howells:

… Howells considers four responses that have been proposed to his conundrum:

- Kaldor and Trevithic[k] – any excess money is automatically extinguished as a result of the repayment of bank debt.

- Chick – the income multiplier process will automatically increase the demand for active balances.

- Laidler – the buffer stock demand for money is a demand “on average” over a period of time, rather than a demand for a fixed stock at a moment of time.

- Moore – “convenience lending,” the rejection of an independent money demand curve, rooted in a “full-blooded rejection of the idea of equilibrium”: In a non-ergodic world, no meaning can be attached to the notion of a unique general equilibrium stock of money demanded.

Howells maintains that the above list offers “promising solutions” to the mechanism that reconciles net new lending to borrowers with the change in the demand for money for the wealth holders. But he concludes that “each … on its own is almost insufficient” for the “reconciliation. As a result, he proposes that variations in relative interest rates, “which can and do occur continuously, provide the key to the fine-tuning required by the balance-sheet identity” …

Frequently in such discussions the accommodative behaviour of the banking system is forgotten. So there is another mechanism as highlighted by Nicholas Kaldor in his book The Scourge Of Monetarism (Oxford University Press, 1982):

As it is, a highly developed banking system already provides such facilities on an ample scale, since it is prepared to accommodate the public’s changing demand between different types or financial assets by altering the composition of the banks’ assets or liabilities in a reverse direction. If the non-banking public wishes to switch its holding of gilts for interest-bearing bank deposits, the banks are ready to supply such deposits at the minimum of inconvenience, and at the same time to place their surplus funds into the gilts which were previously held by the public. Similarly the banks provide easy facilities to their customers for switching balances on current accounts into interest-bearing deposit accounts, or vice versa.

In general banks not only hold government bonds but also other kinds of securities such as mortgage-backed securities, agency debt and so on. In olden days, there was no securitization and banks would hold more government bonds which got substituted. (See the Fed’s H.8 weekly release for data on banks’ assets) [There’s a Geithner ppt which mentions this in one slide, anyone has a link?]

This point is an important one because here the reconciliation happens via changes in quantities. Remember it is not just loans which create deposits but also banks buying bonds from the non-banking system which create deposits.

The answers to these questions can be found systematically by using James Tobin’s asset allocation theory.

Let me mention some positions. At one end are Monetarists for whom the direction of causality is from money to other things. So there may be an excess of money and if so leads to higher expenditure and a hot potato process in which money supply and demand are brought into equivalence by rise in prices of goods and services. It can also lead to a rise in real output but the Monetarists emphasize the price aspect more. In addition they also distinguish between government expenditure and private expenditure and try to point out that the latter is more efficient and so on.

Looking at an economy as a moving picture, as expenditures increase, output rises and there is a rise in prices of goods and services and a rise in the stock of money. Monetarists look at coincident events and assign some strange causalities.

Moving beyond Monetarism, there’s also a view that the reconciliation of the supply and demand for money necessarily happens via a rise in interest rates on everything including bank loans leading to a crisis. Of course that it not true because beyond a point banks will reduce lending instead of offering loans at higher interest rates. Banks have their own animal spirits but this is via tightening credit standards, quality of collateral etc. Also this is not the only outcome because the process of lending and borrowing increases output and income and can stabilize debt ratios. Nonetheless, debts can move into unsustainable territories and financial crisis do happen, and when it happens, there’s a high demand for money and the reconciliation may happen via bankruptcies of firms and the central bank may need to accommodate the rise in demand for money by lending at a large scale since bankruptcies threaten a fall in output.

Of course there are many more mechanisms for the reconciliation which I have avoided. It may happen that due to changes in portfolio preferences, there is a stock market boom and firms will go IPO instead of borrowing from the banking system. So we have economic units who wish to hold less money and more equities and firms borrowing less from the banking system leading to a reconciliation. (A more careful analysis is needed because firms have deposits after having raised funds through an IPO).

Now consider convenience lending. There is of course some truth to it. If you receive you salary on a Friday evening, you are not rushing to allocate newly held deposits into the stock market because it is already closed (unless you have an international brokerage account). So you are holding the deposits non-volitionally. However, subscribing to convenience lending alone is a bit extreme.

Now to QE/LSAP. When the central bank purchases financial assets such as government bonds from the markets, it creates bank settlement balances and deposits in the process. Wealth holders will then purchase other assets and the reconciliation happens via changes in prices of financial assets.

This post is far from any complete analysis of the interesting questions but hopefully I have got readers interested in something. The question on reconciliation asks what reconciliates the demand and supply of money – income, prices (of goods and services or prices in financial markets), quantities and so on. Also, some seem to think that “price clearing” has to do with some notions about an equilibrium. I don’t think these two are the same things. One can have price changes and clearances without appealing to the notion of any “equilibrium”.

In the natural sciences, controversies are settled in a few months, or at a time of crisis, in a year or two, but in the social so-called sciences, absurd misunderstandings can continue for sixty or a hundred years without being cleared up.

– Joan Robinson, 1981 (1979), What Are The Questions And Other Essays – Further Contributions To Modern Economics, M.E. Sharpe

The latest Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin (2014 Q1) will be released on the 14th. It has pre-released two articles which go into money creation and the myths associated with it.

The report is here. The second article Money creation in the modern economy may interest you more but the first is also readable.

Interestingly, the second pape refers to Post-Keynesians : Tom Palley’s 1996 book , Basil Moore’s 1988 book, a JPKE paper by Peter Howells and a 1981 paper by Nicholas Kaldor and J. Trevithick which discusses the reflux mechanism (reprinted in Kaldor’s Collected Economic Essays, Vol. 9). It also refers to James Tobin’s 1963 paper Commercial Banks As Creators Of “Money”.

One negative is the omission of fiscal policy from the discussion altogether and emphasising monetary policy. This underplay of fiscal policy and overemphasis of monetary policy is one deep bias of the profession. The paper also has a slightly different emphasis on what determines the quantity of lending than emphasized by Post-Keynesians but I won’t go into it now. Still the page is worth a look.

Louis-Philippe Rochon and Sergio Rossi have a very interesting article Endogenous Money: The Evolutionary Versus Revolutionary Views in the Review Of Keynesian Economics. I think it was written many years back and was in an unpublished form and has been published now. It is a nice critique of views of some Post-Keynesians such as Victoria Chick and also others such as Basil Moore. For instance, the paper quotes Moore’s view from 2001:

[w]hen money was a commodity, such as gold, with an inelastic supply, the total quantity of money in existence could realistically be viewed as exogenous.

Click the image to visit the ROKE website.

There are also some nice articles in a recent issue of JPKE on neoliberalism and the financial crisis.

Some gossip: The JPKE was initially supposed to have been called Journal of Keynesian Economics but it didn’t make it because the acronym would have been JOKE.

Also, Jayati Ghosh has written an excellent blog article on Thatcherism – the ‘triumph of private gain over social good’ (borrowing words from her).

Matias Vernengo has a recent blog post on the persistence of poverty in the United States. Which reminds me of an interview clip of Anwar Shaikh titled “The Sin Of Our Era”:

click to watch the video on YouTube

Back to formal matters.

What does it mean when an economist says words such as “endogenous”, “exogenous”? Most of the times, economists – mainstream economists – themselves confuse these terms and hence you see a lot of usage of these words in Post-Keynesian economics.

I was reading an article on econometrics by Fischer Black (of the Black-Scholes fame) titled The Trouble with Econometric Models

An exogenous variable is supposed to be a causal variable, if the structure of a model has economic meaning. In fact, it is usually just a variable that is put on the right-hand side of equations in a model, but not on the left-hand side.

Similarly, an endogenous variable is supposed to be a caused variable. In fact, it is usually just a variable that shows up at least once on the left-hand side of an equation

which is fair but there exists another language.

There is however another usage – that is in the control sense.

In an outstanding paper Federal Reserve “Defensive” Behavior And The Reverse Causation Argument, Raymond E. Lombra and Raymond G. Torto point out the following in the footnote:

Apparently no generally accepted concept of an endogenous money stock (or monetary base) has been defined. In statistical theory a variable is endogenous if it is jointly determined with other variables in the system. However, many monetary theorists have chosen to call a variable endogenous only if its magnitude is not under the control of policymakers. Such semantic problems have undoubtedly prolonged this debate.

For the money stock measure such as M1, M2 etc., there shouldn’t be any confusion. The trouble arises for things such as interest rates. For example, some economists may say that if inflation rises, the central bank may/will raise the short-term interest rate and it is endogenous while others will say it is up to the central bank to decide how much to change the interest rate, if at all. Such things lead to a lot of debate.

I like the latter usage (the control sense) but I think it is difficult to exclusively have the same usage.

The word “control” is also misunderstood. Here is a fine article on Wynne Godley in The Times from 16 June 1978 where he details on how misunderstood the word is:

(click to expand)

There was a discussion last week on a social network site on Basil Moore’s book Horizontalists And Verticalists. Someone mentioned he never knew anyone who owned a copy of the book! Lucky me.

I was browsing through my copy and came across this – which I thought I should quote on central bank “defensive behaviour”.

Actually, among Post-Keynesians, Alfred Eichner was the first to understand and highlight the “defensive” nature of central bank open market operations.

Outside PKE, it was a paper of Raymond E. Lombra and Raymond G. Torto titled Federal Reserve Defensive Behaviour And The Reverse Causation Argument which started analyzing the details of the Federal Reserve defensive behaviour and supported the theory of endogenous money on which economists such as James Tobin and Nicholas Kaldor were writing at the time. The term “defensive” was coined by Robert Roosa of the Federal Reserve in the book Federal Reserve Operations In The Money And Government Securities Markets originally written in 1956.

Recently central banks around the world have been doing a lot of things (“unconventional measures”) in trying to “boost” their economies – such as “large scale asset purchases” (QE). For some, recent central bank action is the natural way to start to understand monetary economics. For me, it is first important to understand what they did before the crisis to correctly understand what they have been doing and judge if their actions have any usefulness at all – on a case by case basis.

Anyways, here is from Basil Moore’s book (pages 97-99):

Open-market operations: defensive rather than dynamic?

According to the conventional story taught in most textbooks and worked through by students in countless T-account exercises, central bank open-market security purchases have expansionary effects on the money stock by raising the high-powered base. Central bank security sales conversely lower the high-powered base, and so operate to reduce the stock of money outstanding.

Table 5.2 presents the relationship between changes in total bank reserves, the monetary base, and the Federal Reserve net open-market security purchases or sales. The data are monthly time intervals for the period October 1979 to December 1983. This is the period when quantitative targeting was purportedly at last rigorously instituted. Nonborrowed reserves were avowedly the Fed’s chief operating instrument for controlling the growth rate of the monetary aggregates.

To the student of introductory economics, and even to many economists, these results will surely be startling. On a monthly basis, Federal Reserve net open-market operations fail to explain any of the actual changes in unadjusted or adjusted total reserves! They explain only 5 percent of changes in the unadjusted and only 10 percent of the changes in the high-powered base. In all cases the coefficient on net open-market purchases and sales is extremely small. It has no statistical significance in explaining observed changes in bank reserves. Although the coefficient is statistically significant in explaining the monetary base, its magnitude implies that $1000 of open-market purchases or sales were necessary to change the value of the base by $1!

The explanation for these apparently puzzling results is not far to seek (Lombra and Torto, 1973). From the central bank’s point of view a large number of stochastic nonpolicy factors operate to add or withdraw reserves from the banking system. These factors can be analyzed by an examination of the central bank’s balance sheet identity. This documents the various financial flows that accompany any change in the base: changes in float, changes in the public’s currency holding, foreign capital inflows or outflows, changes in treasury balances held with the Fed, changes in bank borrowing from the discount window. All of these flows are completely outside the control of the monetary authorities. In order to achieve a desired level of the base, these flows must be completely offset by open-market operations.

If the Fed were to take no action in the face of these large stochastic inflows and outflows of funds, the banking system would experience sharp fluctuations in its excess reserve position. Such changes would be unrelated to the Federal Reserve’s policy intentions, and would provoke continued liquidity crises and great instability in interest rates. As a result most Federal Reserve open-market operations are “defensive” and designed to offset the effects of these nonpolicy forces. Central banks operate to make reserves available to the banking system on reasonably stable terms, from day to day and week to week.

Studies of Federal Reserve open-market operations have estimated that more than 85 per cent of Federal Reserve security purchases of [sic] sales are “defensive” (Lombra and Torto, 1973, Forman, Groves and Eichner, 1984). Such flexibility is needed to deal with the very large inherent volatility of money flows. On a week-to-week basis such “noise” in the behaviour of the narrow money supply accounts for dollar changes in reserves of plus or minus $3 billion more than two-thirds of the time. This represents nearly 10 percent of total reserves, which were concurrently in the order of $40 billion (J. Pierce, 1982). On a monthly bias, such “noise” accounts for changes in the money stock or plus or minus 5 percent about two-thirds of the time.