Recently Mario Draghi, the European Central Bank President, has been going around telling everyone that “fiscal consolidation” is the absolutely essential to resolve the Euro Area crisis, given some positive developments. Although, this view of his is known and this has had a big influence on policy, he has become more and more vocal about it in recent weeks. He has also signalled a “positive contagion” – a phrase he seems to have coined.

Here is Mario Draghi talking at the recent annual conference at Davos to John Lipsky. (Link no longer works)

If Draghi is to be believed, “fiscal consolidation” is an absolute necessity for the Euro Area to come out of the crisis.

In a recent press conference from January 10, Draghi said the same:

Question: Could Outright Monetary Transactions (OMTs) lose their magical effect in the markets if no country asks for them?

Second question: Jean-Claude Juncker has said that too much fiscal consolidation could have a negative effect on countries like Spain, because unemployment is so high. What can you say about that?

Draghi: On your first question, you do not have to ask me, ask the markets.

On the second, many comments of this type have been made about several countries in the euro area. My answer to this is that so much progress has already been made, accompanied by so many enormous sacrifices. So reverting to a situation which has been found to be untenable would not be right. We should not forget that this fiscal consolidation is unavoidable, and we certainly are aware that it has short-term contractionary effects. But now that so much has been done I do not think it is right to go back.

[emphasis: mine]

Back in July 2012, when Spanish government bond prices were plunging, Mario Draghi came up with a plan to save the Euro Area by first announcing on July 26 in a conference in London that “Within our mandate, the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro,” and after a pause, “And believe me, it will be enough.”. In the monetary policy meeting on September 6, he outlined a plan by the Eurosystem to buy government bonds without any ex-ante quantitative limits, provided the nations asking this facility agree to terms and conditions – mainly on fiscal policy.

This was greeted with great optimism and the “state of confidence” of the financial markets greatly improved in the next few months. Mario Draghi eventually became the FT Person Of The Year. The fact that nations have a backstop meant that the financial sector has been more willing to finance the governments and the nations actually haven’t felt the need to use the facility so far.

At the time, there was an urgent need to do something and the European Central Bank responded positively to prevent a financial and economic collapse.

While the condition that governments asking for the ECB’s help have to meet is unavoidable for any such plan, Mario Draghi seriously misunderstands the nature of the problem. While it is true that there needs to be structural reforms so that struggling Euro Area countries become more competitive relative to their partners and aim to improve their exports to reduce imbalances within the Euro Area, a Euro-Area wide fiscal contraction will fail to achieve this in any sustainable way. Structural reforms aka wage cuts, will further deflate demand in those nations as Michal Kalecki taught us.

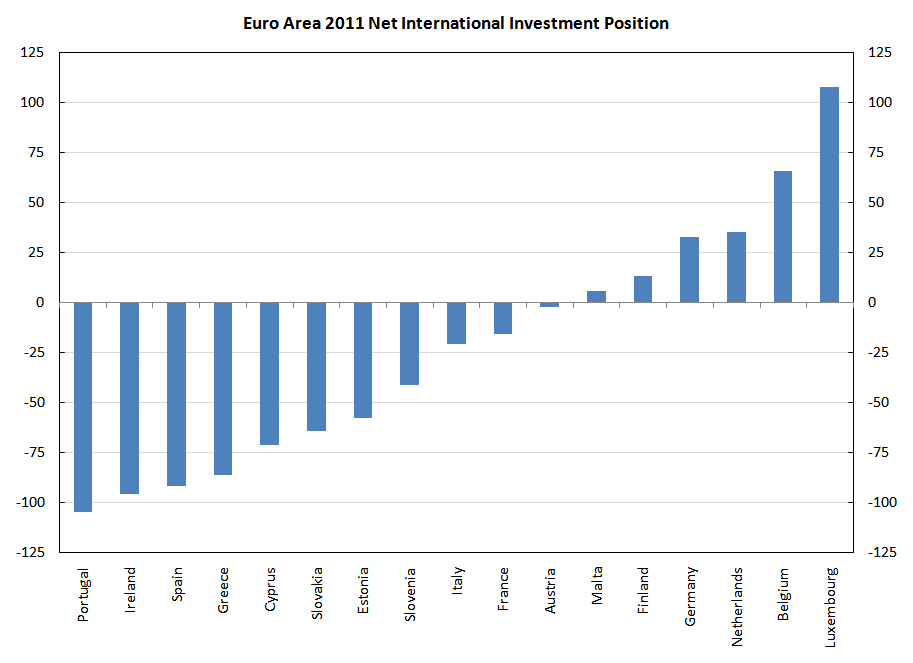

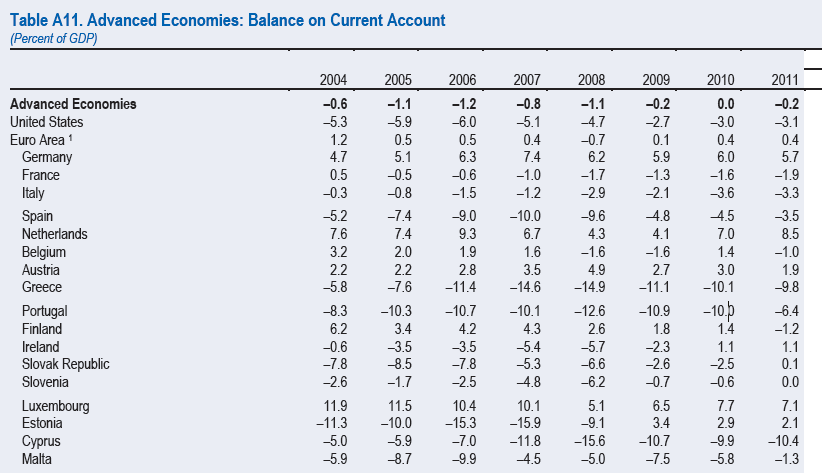

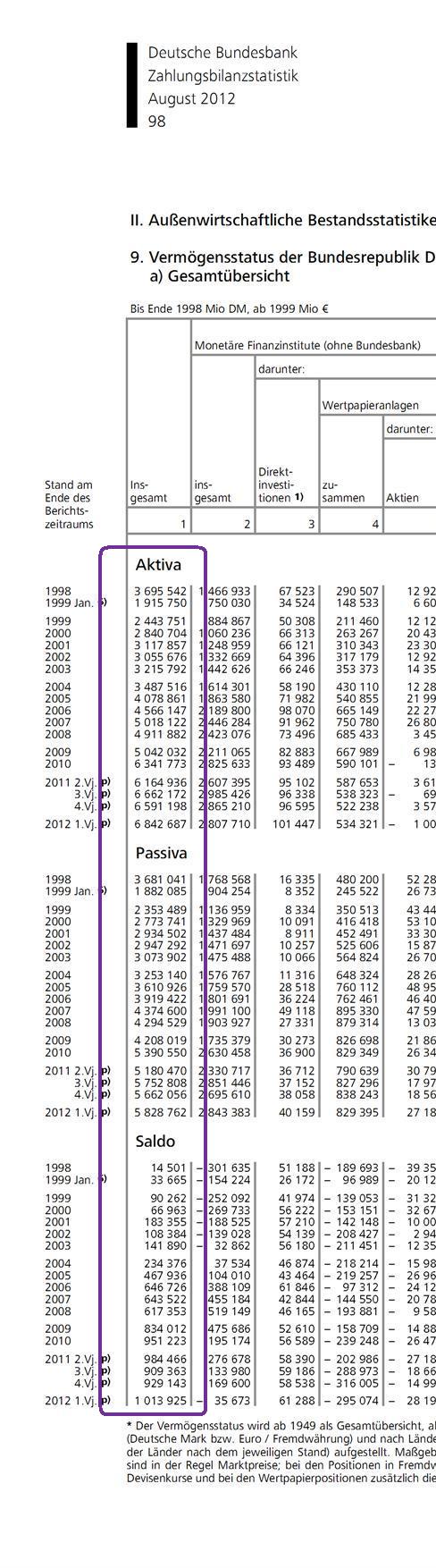

Take Spain for example. Its current account is coming back to balance but this has been the result of a huge deflation of domestic demand and no wonder its unemployment rate hit 26% recently. Statements such as “fiscal consolidation is unavoidable” put all the burden on weaker nations. The Euro Area actually needs a fiscal expansion in creditor nations and although a relatively tighter fiscal policy in the debtor nations compared to creditor nations, an expansion compared to the present state nonetheless. In the long term it needs to form a political union – not like the ones floated by European leaders.

The weaknesses of the Euro Area going forward has been highlighted by Charles Goodhart in a recent appearance in the Economic and Financial affairs session of the UK Parliament. Here is the link to the video.

Also, in December 2012, Draghi and the EU leaders presented a plan Towards A Genuine Economic And Monetary Union. Again this approach has the same errors as the plans floating around since decades and debunked by Nicholas Kaldor in 1971 in one of the most prescient articles ever written. See this post Nicholas Kaldor On European Political Union. The European leaders are seriously mistaken to think of any of their plans as “genuine”.

Somehow, the Monetarist counterrevolution of the 1970s seems to have forever distorted the vision of economists and economic advisers to politicians even if they do not think they are Monetarists.