This is a note by Eladio Febrero Panos sent to me by Sergio Cesarrato.

by Eladio Febrero Paños

Area de Teoria Economica, Facultad de Economicas, UCLM Pza Universidad no. 1, 02071 Albacete, Spain

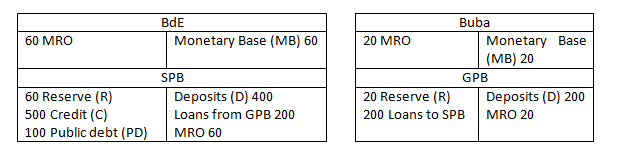

Let us assume the following initial situation.

There are two private banks, one in Spain (SPB) and another one in Germany (GPB); we have also two central banks (BdE for Spain and Buba for Germany). For simplicity’s sake, we omit the ECB which connects them through the TARGET2 (T2) system.

Imagine the following balance sheets which (I hope) are self evident:

This figure accounts for the import of a commodity made in Germany by a Spanish agent (amounting to 200 monetary units, m.u. onwards). This import generated a deposit which was then “lent” by GPB to SPB. With this loan, T2 claims and liabilities cancelled out.

Also, we are assuming a compulsory reserve system, with a reserve coefficient of 10% on collected deposits. This is an overdraft system (Lavoie[1] has described this very often), so that each central bank lends to private banks in its jurisdiction the reserves that the former requires the latter to hold.

I think that, up to this point there is nothing controversial.

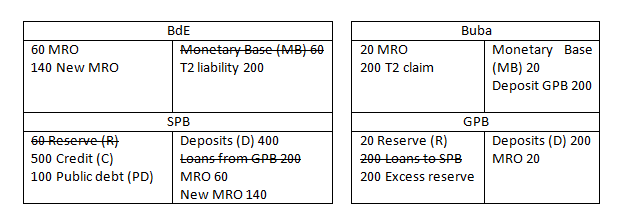

Next, we shall assume that GPB does not wish to roll over its loan to SPB because whatever reason. Consequently, GPB prefers to bring money at home.

How can this be done, if SPB does not have enough reserves? There are two alternatives.

In the first one, SPB would try to sell its public debt (PD). This option has at least two problems.

Firstly, even if SPB sells all its PD it will not obtain proceeds enough to cancel the loan from GPB.

Secondly, the price of PD would plummet and this is a problem for the implementation of monetary policy:

- PD is collateral when borrowing in the interbank market; if its value falls SPB would have it harder to borrow there; and consequently, the credit supply would shrink.

- the yield of PD is the reference when calculating the interest rate on loans to solvent borrowers; if the price of PD plummets its yield skyrockets. This would affect negatively to the credit market;

- there is a balance sheet effect: if the value of PD falls, SPB’s balance size shrinks because part of its assets has a lower value; if its liabilities remain the same, SPB’s equity would shrink as well and this would lead to less credits.

The central bank aims at preventing this situation (here). Because of this, it will provide SPB with liquidity. And here we have the second alternative.

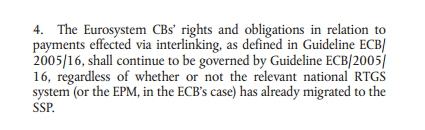

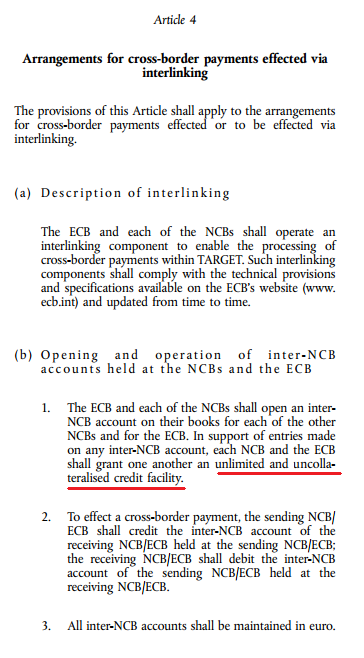

The BdE will lend to SPB, either through the marginal lending facility, providing a loan, or through a MRO / LTRO (for our discussion this does not matter). If it makes a MRO, we shall have:

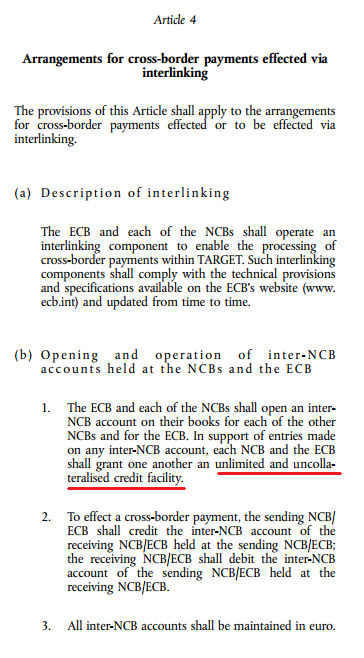

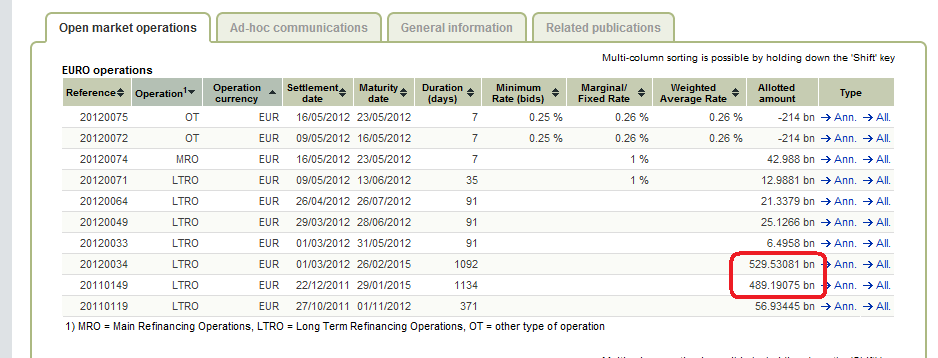

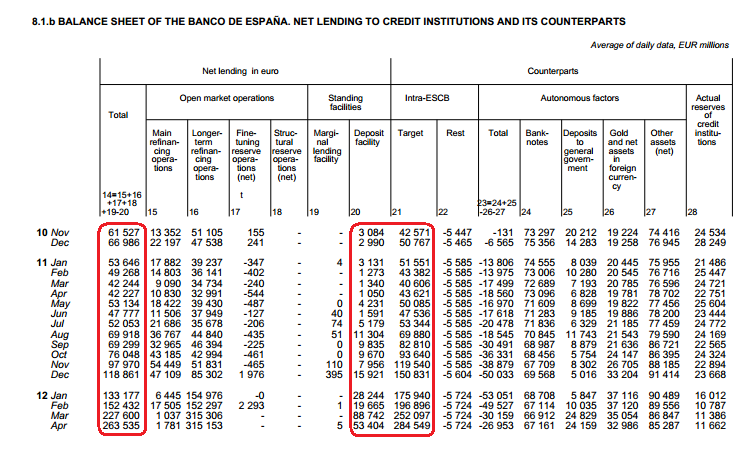

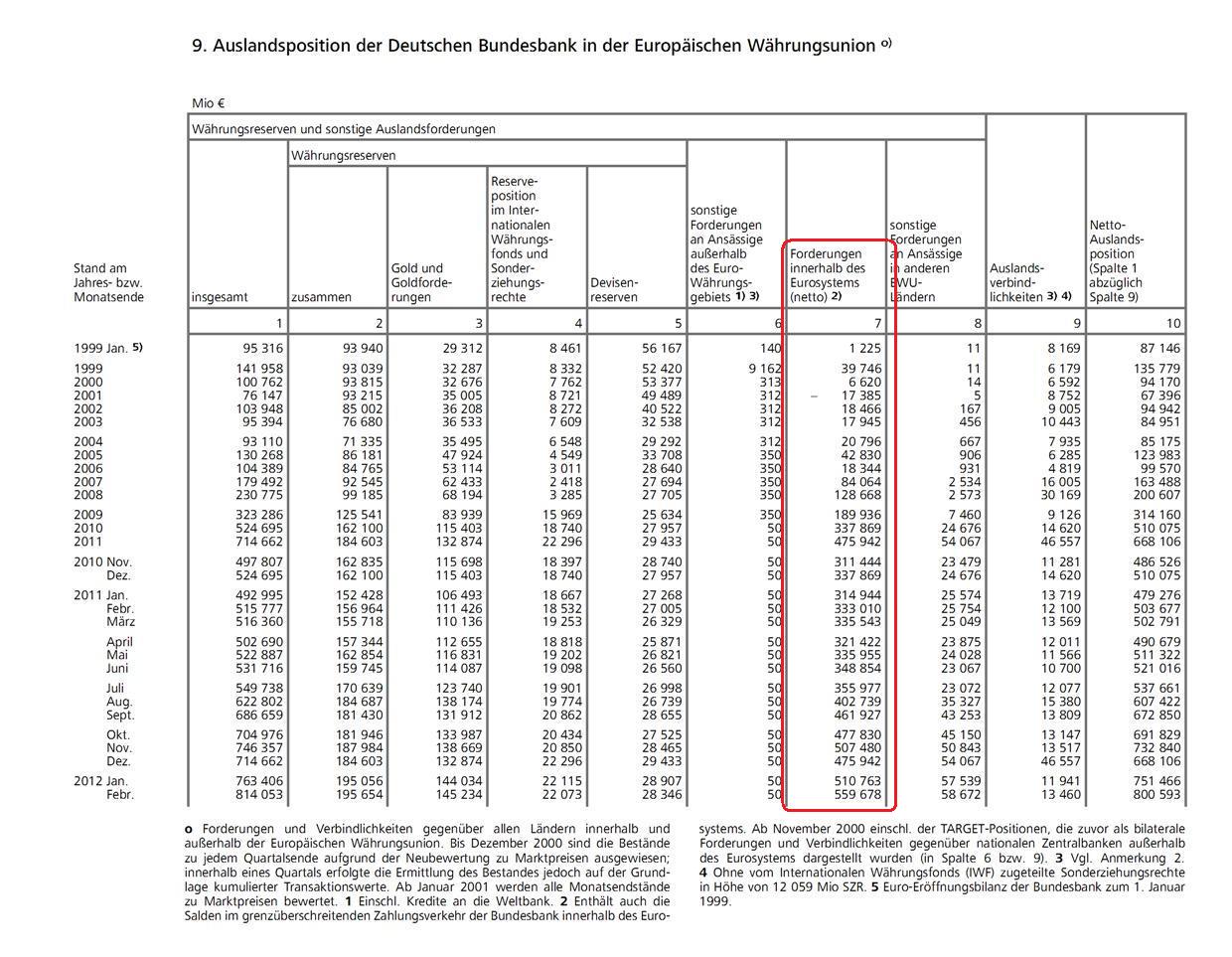

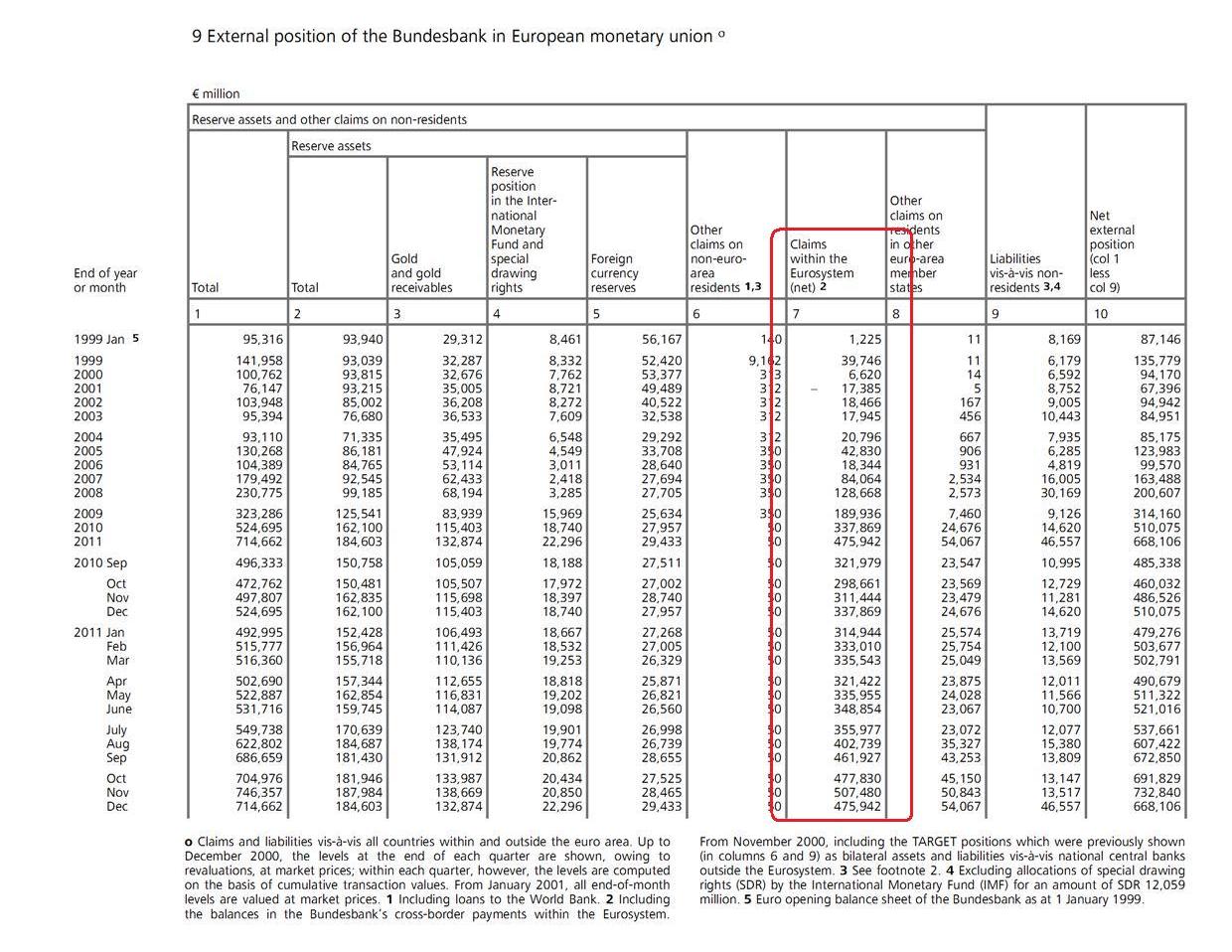

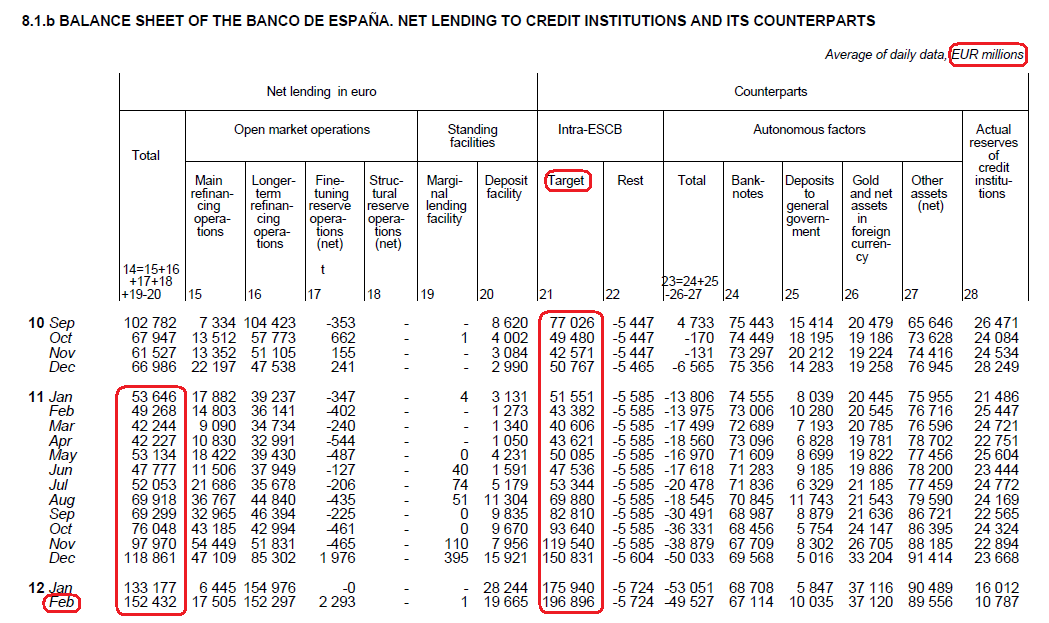

The ECB, through peripheral NCBs (national central banks) is providing liquidity to make it possible for German investors (and also peripheral ones) to carry their money to a safe harbor (in Germany, but also Luxembourg). T2 imbalances are the consequence of this monetary policy.

It should be noted that this is not a specific policy aiming at financing a current account imbalance in the periphery (here). It is not a fiscal policy, as Sinn has claimed so often.

It is an automatic policy, which makes it possible the payment system to run smoothly, something which is mandatory for the ECB.

Contrary to Sinn who argues as if the EMU is a club of countries with a fixed exchange regime, the EMU is a monetary union. In the EMU, countries are for the union like regions or autonomous communities for a nation-state. If you move your savings from a deposit in Banca San Paolo to Unicredit, and the former has no reserves deposited in the Banca d’Italia, the latter would create money and then credit the reserve account of Unicredit so your money would be there now. In its turn Banca d’Italia would acquire a claim on Banca San Paolo. If the latter has a solvency problem, then Banca d’Italia would force it to disappear (after selling its assets). If it has just a liquidity problem, Banca d’Italia probably would let it continue operating and wait until it can pay back its debt.

It should be noted that if Banca d’Italia in the example just above, or the European System of Central Banks (in this discussion on T2) does not provide with liquidity the banking system, it would collapse: there would be a bank run and the whole economic system would have very serious problems.

It is in this sense that T2 imbalances are the consequence and not the cause of the problems within the EMU.

It should be noted also that if, instead of having a central bank in Spain and another one in Germany, but just one for the whole EMU, T2 claims and liabilities would cancel out.

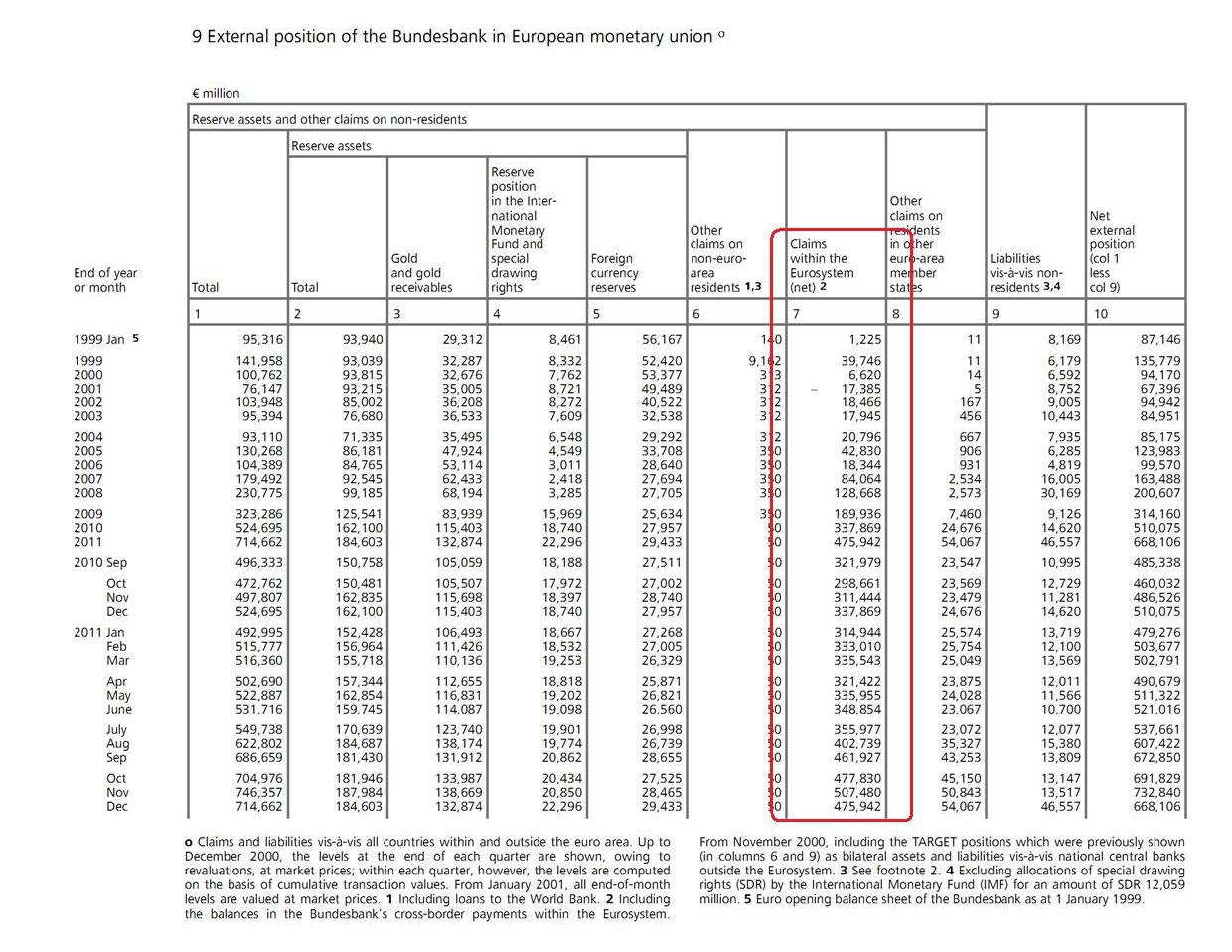

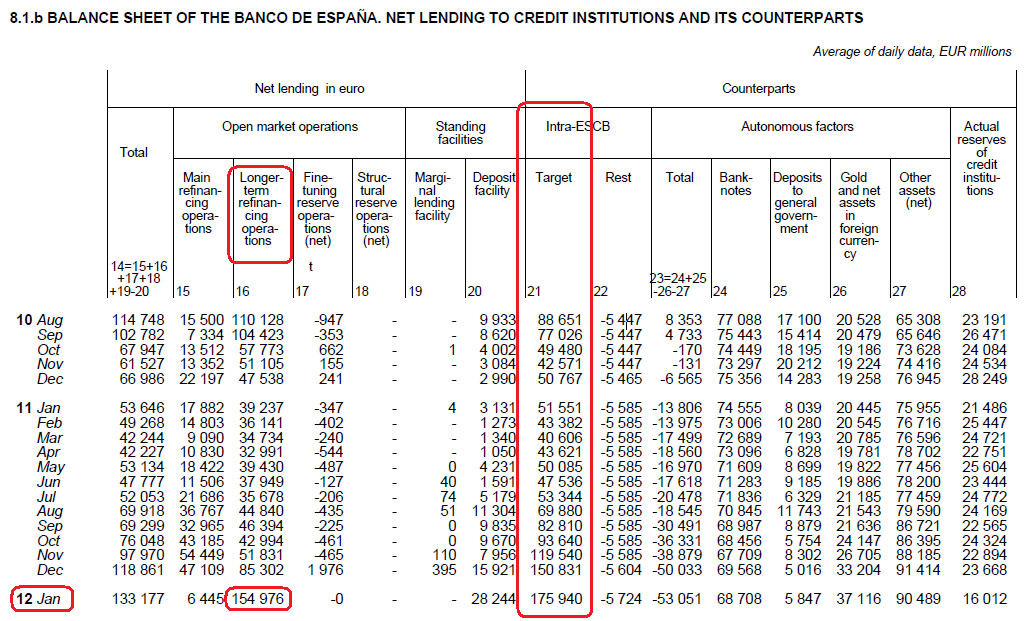

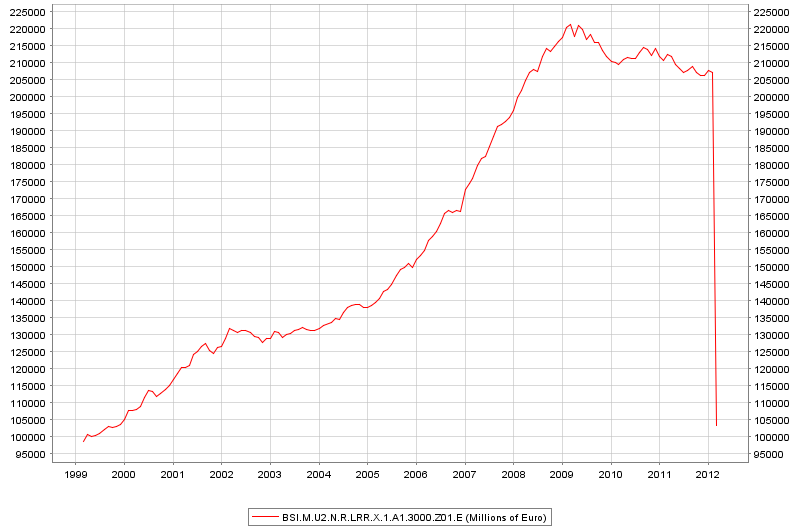

Also, you will find here statistical information about the relation between MRO and T2 for Spain, drawn from the Banco de España website (here and here in epigraph no. 8.1 if you click on ‘Series temporalesdel cuadro 8.1, you will download an excel file with the numerical information included in the pdf file). There you will see that there is a nice correlation between MRO and T2 imbalances during the last year or so (probably the correlation improves if you add LTRO to MRO).

References

- Marc Lavoie, A Primer On Endogenous Credit-Money in Modern Theories Of Money – The Nature And Role Of Money In Capiatlist Economies, Edward Elgar, 2003, ed. Louis-Philippe Rochon and Sergio Rossi. (Google Books Link)