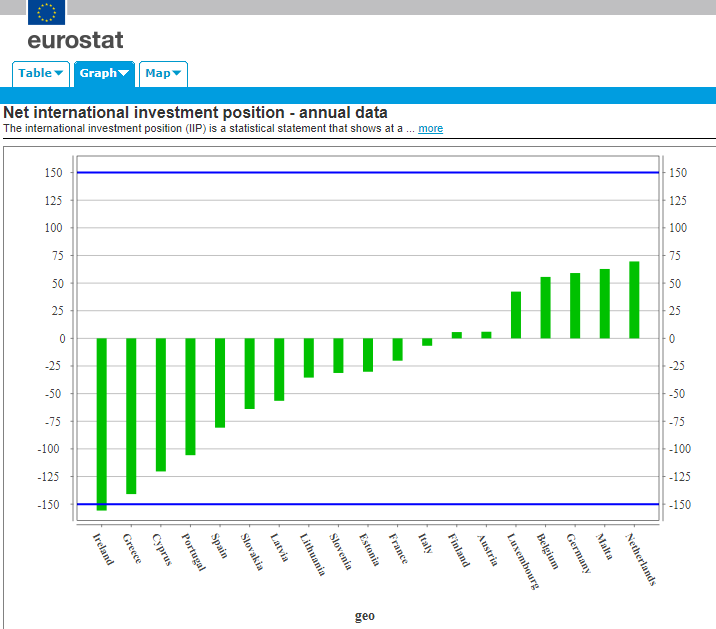

With crisis in Italy, the Euro Area is back in news! But it is not just Italy, the crisis is far from over, as this chart from Eurostat—my favourite—illustrates:

The Euro Area doesn’t have a central government with large fiscal powers and hence there is nothing to keep imbalances in check. So some countries—with no fault of theirs—accumulated large debts. The net international investment position captures the financial position of a country. If it is positive, it is a creditor to the world, if it is negative it is a debtor of the world. If NIIP/GDP is large negative, then there is a problem. It’s difficult to say how large it can go, since it depends on how long markets and official institutions allow it to go. The need to keep it sustainable puts a downward pressure on GDP.

As Nicholas Kaldor wrote in The Dynamic Effects Of The Common Market, in the New Statesman, 12 March 1971:

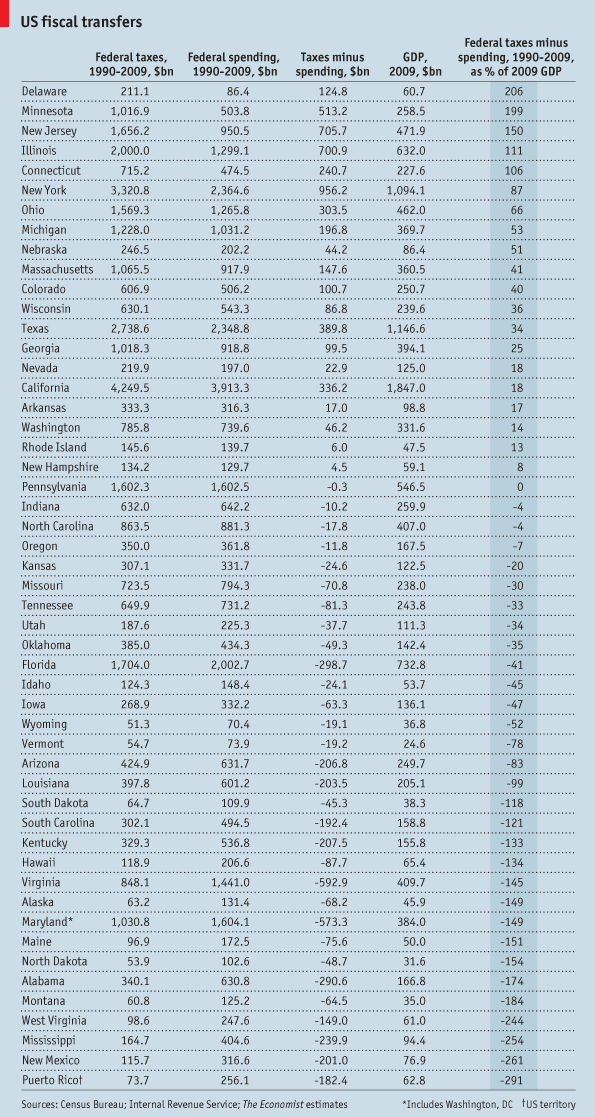

… the objective of a full monetary and economic union is unattainable without a political union; and the latter pre-supposes fiscal integration, and not just fiscal harmonisation. It requires the creation of a Community Government and Parliament which takes over the responsibility for at least the major part of the expenditure now provided by national governments and finances it by taxes raised at uniform rates throughout the Community. With an integrated system of this kind, the prosperous areas automatically subside the poorer areas; and the areas whose exports are declining obtain automatic relief by paying in less, and receiving more, from the central Exchequer. The cumulative tendencies to progress and decline are thus held in check by a “built-in” fiscal stabiliser which makes the “surplus” areas provide automatic fiscal aid to the “deficit” areas.