Radio Open Source has a nice intervew of Noam Chomsky by Christopher Lydon where they discuss neoliberalism among other things. Audio, transcript.

What is neoliberalism?

This question is asked frequently, especially by those who deny that such a thing exists (not the interviewer of course!). In my experience, those who deny it the most are the most neoliberal. At any rate—although I’ll try to describe what it is—it’s not important to get the definition right. Isn’t the creation of the Euro Area without a central government neoliberalism?

In the above interview, Chomksy is faced with this question:

CL: You famously said about neoliberalism that it’s not new, and it’s not liberal. Do you want to define it for people who just landed from Mars?

NC: Well, it’s a kind of a mixture. The rhetoric is free market, individual choice and so on. That’s the rhetoric. The reality is rather different. It’s individualism and market for you but state power for me. So take a look, say, at the actual institutions like the World Trade Organization or NAFTA, what are called the “free trade agreements.” The media calls them “free trade agreements.” They’re not free trade agreements. They’re investor rights agreements. They’re highly protectionist. They provide unprecedented protection backed by state power for major conglomerates like the pharmaceutical industry, media conglomerates, others.

That’s quite accurate, although Chomsky didn’t take the effort to define it but just described it as it is.

A lot of people try to distinguish neoliberalism and the New Consensus of economics. It’s certainly true that you can find examples of economists who believe in neoclassical economics or the new consensus or whatever you call it but don’t exactly advocate policies of neoliberalism. But, I’ll just categorize them as being deceived by economists. Orthodox economics is neoliberalism, except for minor differences. The former is an academic subject built to defend the latter, which is a political ideology. New Consesus Economics exists in academia because neoliberals and conservatives in political positions award them. Neoliberals then quote their research to defend policies.

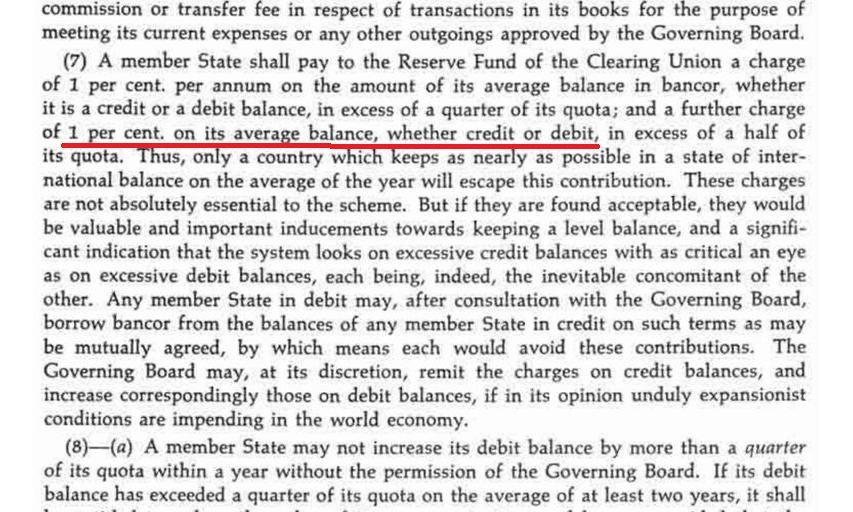

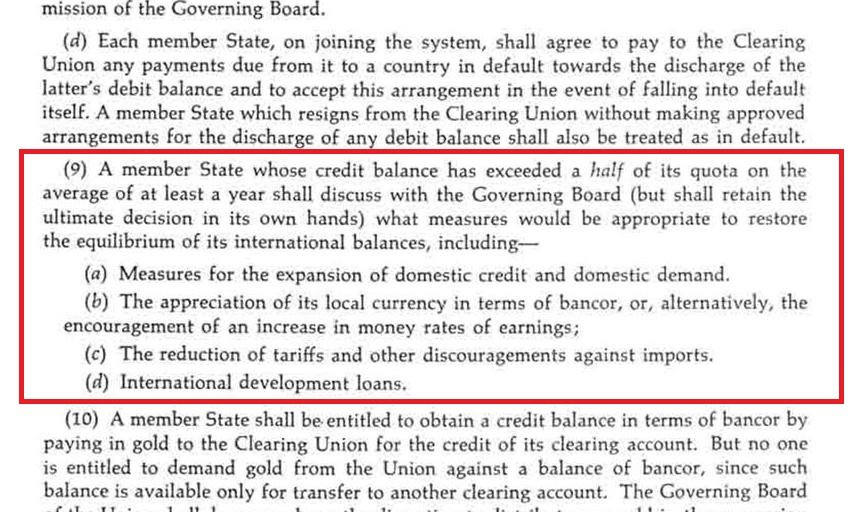

Neoliberalism is based on three extremely damaging ideas of neoclassical economics: free trade, tight fiscal policy and the production function.

After the economic and financial crisis, it’s true that economists have conceded that fiscal policy has strong positive effects. Yet, it’s situational in most occasions. When a neoliberal party is in power, they might advocate fiscal expansion, at least make it look like they’re doing it. Also, although they sound as if they are unorthodox about it, they’ll rarely concede that they had a different position before the crisis. They’ll make it look like they have always believed their current positions since their undergraduate days. They’ll also pander to people who might want to hear otherwise. So they have different public and private positions. In other words, doublespeak about fiscal policy is the hallmark of a neoliberal.

But although economists have shifted their positions on fiscal policy—at least when it suits them—their voice about free trade has grown stronger. It is here that Chomsky’s point about “market for you but state power for me” appears the most illuminating. Rich nations are rich due to their success in international trade and they try to impose it on poor nations by hook or crook. This requires the cooperation of governments because agreements are negotiated by governments. Poor nations generally are sceptical about economists’ narratives but are arm-twisted by governments of rich nations and there is an establishment around the government which pushes such things both directly and indirectly by controlling the narrative (or control of opinion and manufacturing consent, as Chomsky might say).

Another aspect about neoliberalism is the politics around wages. As Thomas Palley says,

With regard to income distribution, neoliberalism asserts that factors of production—labor and capital—get paid what they are worth. This is accomplished through the supply and demand process, whereby payment depends on a factor’s relative scarcity (supply) and its productivity (which affects demand).

The theoretical basis for this is the narrative build in neoclassical economics using the notion of a production function and marginalism. Reality check: In the late 70s and early 80s, orthodox economists promoted government policies of high interest rates and this created unemployment and led to drastic weakening of labour unions. They were also weakened by laws. Again, markets for you but state power for me.

To quote Chomsky again from the interview,

[neoliberalism’s] crucial principle is undermining mechanisms of social solidarity and mutual support and popular engagement in determining policy.