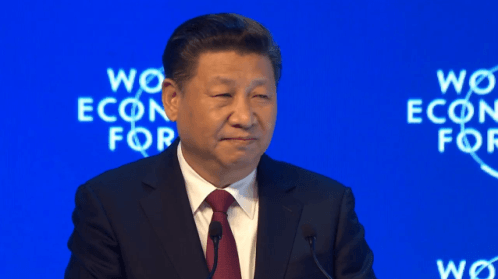

Xi Jingping, the President of the People’s Republic of China spoke today at the World Economic Forum at Davos.

click the picture to see the video on YouTube. Transcript here

In his speech, he argues for globalization, although also points out the negatives. He says:

We must remain committed to developing global free trade and investment, promote trade and investment liberalization and facilitation through opening-up and say no to protectionism. Pursuing protectionism is like locking oneself in a dark room. While wind and rain may be kept outside, that dark room will also block light and air. No one will emerge as a winner in a trade war.

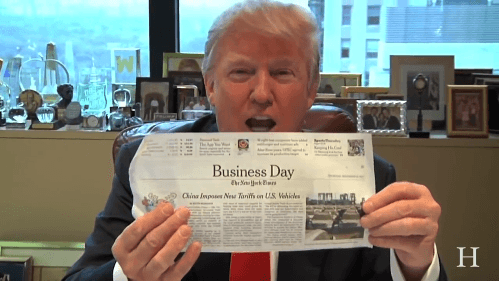

The timing of this speech is not surprising because it comes at a time when Donald Trump is going to become the President of the United States and is threatening to take action on China. Although economists and policy wonks have kept denying it, the Chinese government’s trade practices have been highly damaging to the United States’ economy. For China, “free trade” has been highly advantageous. By keeping its exchange rate at a highly devalued level, the government of China has made large gains for its economy at the expense of the rest of the world. But this “currency manipulation” is not the only unfair practice. Producers in China do what’s called predatory pricing in which prices of their products are kept low in the international markets to gain market share and harm competitors.

It’s an irony of our times that Donald Trump, a right-wing leader is insistent on taking action on China via protectionism, i.e., by setting large tariffs on Chinese exports to the US. It’s even more ironic that China is communist and is declaring free trade to be good.

China’s Mercantalism reminds us of a quote by Joan Robinson. In her 1977 essay What Are The Questions?, she says:

From a long-run point of view, export-led growth is the basis of success. A country that has a competitive advantage in industrial production can maintain a high level of home investment, without fear of being checked by a balance-of-payments crisis. Capital accumulation and technical improvements then progressively enhance its competitive advantage. Employment is high and real-wage rates rising so that “labor trouble” is kept at bay. Its financial position is strong. If it prefers an extra rise of home consumption to acquiring foreign assets, it can allow its exchange rate to appreciate and turn the terms of trade in its own favor. In all these respects, a country in a weak competitive position suffers the corresponding disadvantages.

When Ricardo set out the case against protection, he was supporting British economic interests. Free trade ruined Portuguese industry. Free trade for others is in the interests of the strongest competitor in world markets, and a sufficiently strong competitor has no need for protection at home. Free trade doctrine, in practice, is a more subtle form of Mercantilism. When Britain was the workshop of the world, universal free trade suited her interests. When (with the aid of protection) rival industries developed in Germany and the United States, she was still able to preserve free trade for her own exports in the Empire. The historical tradition of attachment to free trade doctrine is so strong in England that even now, in her weakness, the idea of protectionism is considered shocking.

[boldening: mine]

In her article she was talking about how free trade is a subtle form of mercantilism. What she was imagining was a nation typically not seen as mercantilist but pro-free-trade but that the latter is a subtle form of the former. In the present case, China is seen more as Mercantlist (although the establishment economists deny it) and it’s promoting free trade now. So these two ideologies have a lot in common. Jinping’s speech makes this obvious. Free trade is now a not-so-subtle form of mercantilism.