The new paper by Gennaro Zezza and Michalis Nikiforos for the Levy Institute, surveying the literature on stock-flow consistent models has a discussion on the concept of equilibrium:

In the short run, “equilibrium” is reached through price adjustments in financial markets, while output adjustments guarantee that overall saving is equal to investment. However, such “equilibrium” is not a state of rest, since the expectations that drive expenditure and portfolio decisions may not be fulfilled, and/or the end-of-period level for at least one stock in the economy is not at its target level, so that such discrepancies influence decisions in the next period.

In theoretical SFC models, the long-run equilibrium is defined as the state where the stock-flow ratios are stable. In other words, the stocks and the flows grow at the same rate. The system converges towards that equilibrium with a sequence of short-run equilibria, and thus follows the Kaleckian dictum that “the long-run trend is but a slowly changing component of a chain of short-run situations; it has no independent entity” (Kalecki 1971: 165). The adjustment takes place because stocks and stock-flow ratios are relevant for the decisions of the agents of the economy. If stocks did not feed back into flows, the model may generate ever-increasing (or decreasing) stock-flow ratios: a result that might be stock-flow consistent, but at the same time unendurable. The convergence towards the long-run equilibrium also depends on more conventional hypotheses regarding the parameters of the model.

So equilibrium is a state where stock-flow ratios are stable.

Of course equilibrium just means that and doesn’t automatically translate to full employment, for example. One can imagine stock-flow ratios such as public debt/gdp, private debt/gdp may converge to some level such as 80%, 50% respectively but with unemployment at, say, 5%.

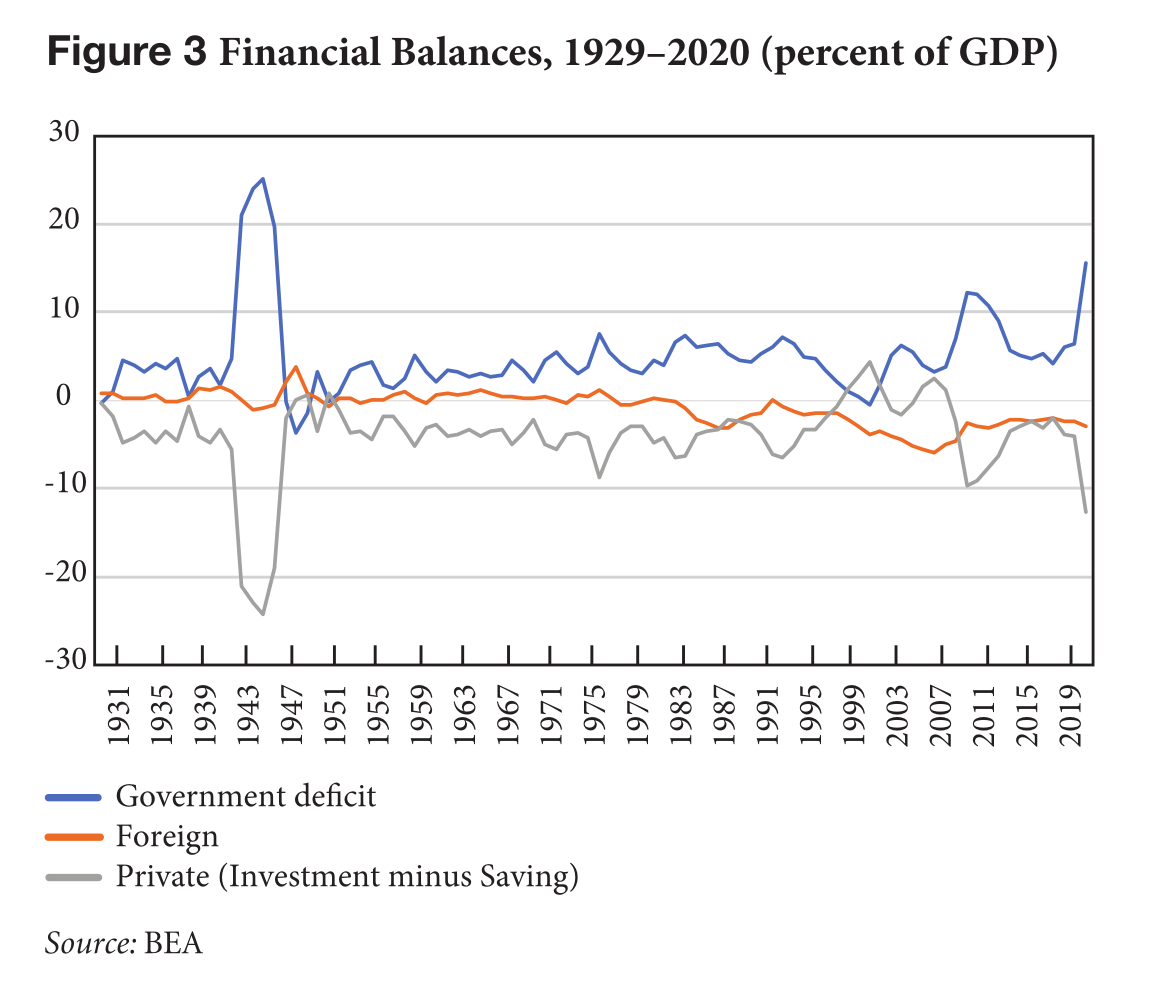

Also, it’s worth mentioning—especially in open economies—there is in general no automatic/market mechanism which guarantees that stock-flow norms are converging to some stable ratios.

Let me offer an alternative viewpoint for the short run.

In the short run, there’s really no concept of equilibrium because there is no heavenly Walrasian auctioneer in most markets. As pointed out by Nicholas Kaldor, there are dealers who are both buyers and sellers simultaneously. Dealers quote bid/ask prices and the quantities they are willing to buy or sell. Since there is a mismatch in demand and supply of “outside buyers” and “outside sellers”, dealers accumulate inventories or stocks. Dealers make a business out of the bid-ask spread. In non-financial markets, the terminology is slightly different. You won’t find a board with bid/ask prices at a car dealer, but the concept is similar. Here even the producer has inventories in the goods market. In the services market, whatever is demanded is supplied (or put in queue or refused if capacity is reached).

So there’s no equilibrium to be reached in the short-run. It’s always in disequilibrium. Sometimes neoclassical authors make it look like accounting identities are violated in disequilibrium and satisfied in equilibrium arranged by the Walrasian auctioneer. But in SFC models, it’s illogical to have such a thing. Accounting identities must always be respected. At all times, between all time periods, even infinitesimally small.

In real life, especially because of complications of the open economy, there is no such thing as an equilibrium or a tendency to move toward any equilibrium via market forces.

Still, the concept of equilibrium is useful even in SFC models. One can start with a state with a stable stock-flow ratios and then study what happens if some parameter or some exogenous variable is changed or a set of them are changed simultaneously. The dynamics may or may not reach equilibrium in the long run but we can study what happens in the traverse.