Some of the previous posts went into the economic concept of Private Saving and Private Saving Net of Investment. For a closed economy these are:

Private Saving = Private Investment + Budget Deficit

Private Saving Net of Investment = Budget Deficit

For an open economy, we add the current balance of payments to the right of both these equations.

So we have the sectoral balances identity:

NPS = DEF + CAB

for Net Private Saving or Saving Net of Investment. Confusingly, Net Saving is used to mean Saving Net of Consumption of Fixed Capital. Consumption of fixed capital is the national accounting equivalent of depreciation but since there is a different accounting treatment, the former phrase is used.

In addition to Investment by the private sector, there’s also public investment and we need a bookkeeping concept of National Saving.

Just like we consolidated the domestic private sector into one, we could also consolidate the whole nation for specific purposes.

First take a closed economy. Since Income = Expenditure and Saving is defined so that consumption and investment expenditures are treated differently, we have

Gross Saving = Gross Domestic Investment

To get Net Saving, one has to subtract consumption of fixed capital from both sides.

Economies however are open. Hence we need to modify the above equation. Simultaneously taking depreciation into account, we have:

Net Saving = Gross Domestic Investment – Consumption of Fixed Capital + Current Balance of Payments

Remember this Net Saving is different from the other usage which is Saving Net of Investment.

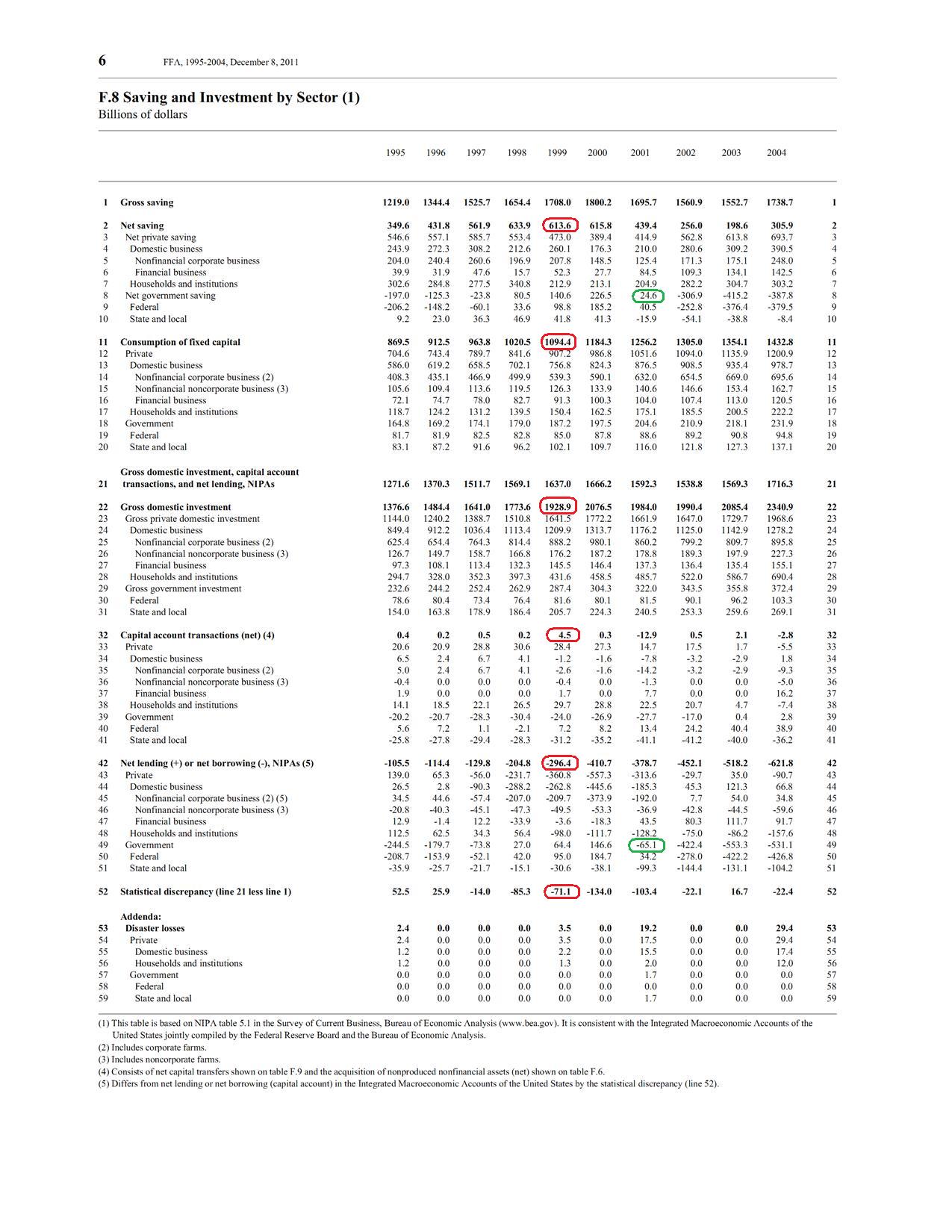

Before verifying that this is indeed the case for the United States, it is worth mentioning that the difference between saving and surplus (or financial balance) applies to the government sector as well. The following is from the Table F.8 of the Z.1 Flow of Funds Accounts of the United States.

(click to expand and click again to expand)

So in green – for the year 2001 for the United States – you see both the gross saving and saving net of consumption of fixed capital of the government sector is positive whereas the government’s budget balance is in deficit.

This shouldn’t be surprising given we saw the same for the private sector.

Back to national saving, we can verify the identity. The current balance of payments is a nation’s income minus expenditure (only in a closed economy, these two are equal). If this is positive, the nation as a whole has a positive net lending. Else, it is a net borrower.

The identity can be seen using the numbers circled in red (and including the statistical discepancy).

The Paradox Of Thrift

The analysis above can mislead one into believing that since “saving” is a positive word, the nation as a whole should save by whatever means – such as by inducing the household sector to increase its propensity to save or aiming for a balanced budget (or worse, aiming to retire the public debt).

Both ideas are vacuous. A spontaneous increase in the propensity to save works by reducing the output and a tight fiscal stance achieves the same i.e., reducing the national saving or private saving as a whichever is the case – as a result of lower demand and output.

The Loanable Funds Fallacy

The simple accounting relations are also used in economics textbooks to promote saving in general because due to the above identity, one can be fooled into believing that a higher saving leads to higher investment. Again such ideas are promoted in public debates to argue against higher government expenditure and to even promote making balanced budget constitutional! The story goes that higher saving allows more investment because supposedly there are more funds to lend for investment.

This is based on the incorrect notion of the exogeneity of money. While this cannot be discussed in a single post, it’s where ideas of endogenous money and Horizontalism are illuminating.

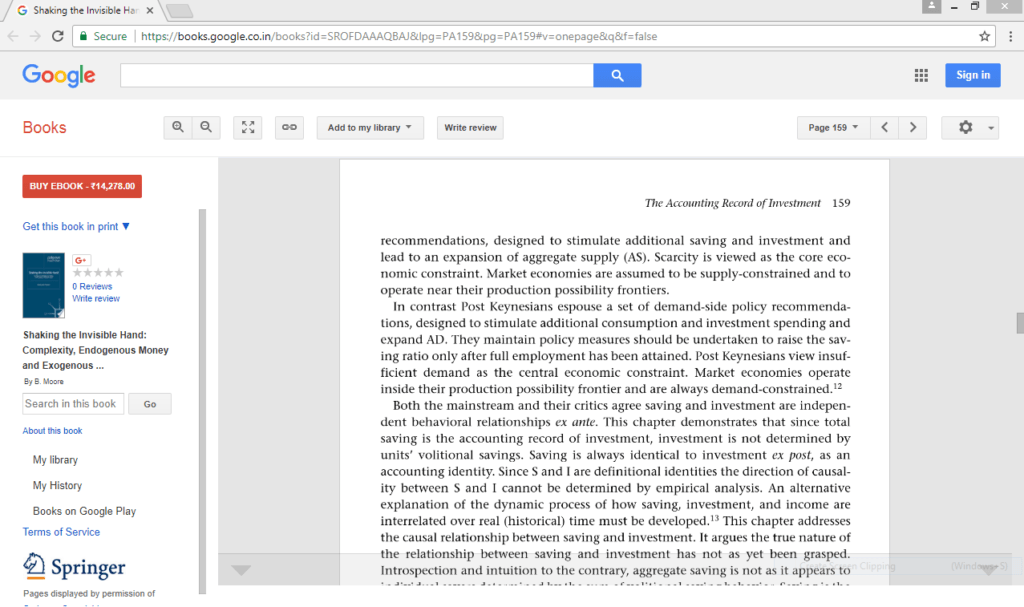

Basil Moore had an article titled Saving Is The Accounting Record Of Investment, where he discusses some of the points here – never mind his claim that “total saving on an economy cannot reflect the volitional behavior of savers”. Here’s a Google Books preview from his book Shaking The Invisible Hand:

click to view on Google Books

Mercantilism

The Mercantilists observe the accounting identity about national saving and the fact that it is related to the balance of payments and conclude that foreign trade is highly important in the growth of nations and hence well being and quality of life. The connection is that saving achieved via running a trade surplus with the rest of the world increases a nation’s net worth. To promote less consumption, the same mantra of national saving is used. So it is related to the paradox of thrift.

These ideas are used in public discussions on the problem of the external sector imbalance whether one believes in Mercantilism or not (their idea of rejection of the invisible hand). An increase in the household propensity to save (achieved by whatever means) or an attempt to reduce the budget balance by a tighter fiscal stance improves the current account balance, only because it results in a lower domestic demand and output and hence higher unemployment – all undesirable. That of course does not mean that one can unilaterally relax fiscal policy but just points to a more international effort needed badly right now to solve the problem of global imbalances.

While there is some truth to Mercantilists’ view, it’s for slightly different reasons – it is advantageous so some in one sense and injures others and hence inures everyone in the end.

Here’s Basil Moore on Keynes (from his 2006 book Shaking The Invisible Hand, pp 400-402):

In the General Theory Keynes introduced open economy considerations in his discussion of Mercantilism. He argued that the Mercantilists had been correct in their belief that a favorable balance of trade was desirable for a country, since increases in foreign investment increase domestic AD exactly like increases in domestic investment:

When a country is growing in wealth somewhat rapidly, the further progress of this happy state of affairs is liable to be interrupted, in conditions of laissez-faire, by the insufficiency of the inducements to new investment. … the well-being of a progressive state essentially depends … on the sufficiency of such inducements. They may be found either in home investment or foreign investment … which between them make up aggregate investment. … The opportunities for home investment will be governed in the long run by the domestic rate of interest; whilst the volume of foreign investment is necessarily determined by the size of the favourable balance of trade. …

Mercantilist thought never supposed that there was a self-adjusting tendency by which the rate of interest would be established at the appropriate level…

In a society where there is no question of direct investment under the aegis of public authority,… it is reasonable for the government to be preoccupied … [with] the domestic interest rate and the balance of foreign trade. … when nations permit free movement of funds across national boundaries the authorities have no direct control over the domestic rate of interest or the other inducements to home investment, measures to increase the favourable balance of trade [are] the only direct means at their disposal for increasing foreign investment; and, at the same time, the effect of a favourable balance of trade on the influx of precious metals was their only indirect means of reducing the domestic rate of interest, and so increasing the inducement to home investment.

Keynes emphasized that any domestic employment advantage gained by export-led growth was a zero-sum game and “was liable to involve an equal disadvantage to some other country.” He argued that export-led growth aggravates the unemployment problem for the surplus nation’s trading partners, who are forced to engage in “an immoderate policy that (may) lead to a senseless international competition for a favourable balance, which injures all alike.” The traditional approach to improve the trade balance has been to attempt to make the domestic export and import-competing industries more competitive, either by forcing down nominal wages to reduce domestic production costs, or by devaluing the exchange rate. Keynes argued that gaining competitive gains by reducing nominal price variables would tend indirectly to foster a state of global recession. One’s trading partners would be forced to attempt to regain their competitive edge by instituting their own restrictive policies. When nations fail jointly to undertake expansionary policies to raise domestic investment and generate domestic full employment, free international monetary flows create a global environment where each nation has national advantages in a policy of export-led growth. The pursuit of these policies will lead to a race to the bottom, that “injures all alike.”

the weight of my criticism is directed against the inadequacy of the theoretical foundations of the laissez-faire foundations upon which I was brought up and which for many years I taught—against the notion that the rate of interest and the volume of investment are self-adjusting at the optimum level, so that preoccupation with the balance of trade is a waste of time.

These apposite warnings of Keynes have gone virtually unnoticed as mainstream economists have waxed enthusiastic about the benefits of liberalized financial markets and the export-led economic miracles of the Asian “Tigers,” and now the miracle of China. Modern economies have become more open than when Keynes was writing, so it is imperative that Keynes’ open economy analysis becomes better known.