This is a continuation of a recent post at this blog, Public Debt And Current Account Deficits, in which I argued that the current account balance of payments affects the public debt.

A usual objection to the connection is that the two deficits—current account deficit and the budget deficit—although connected by an identity, don’t move together and in fact move in the opposite direction frequently. This point was raised by the blog Econbrower, yesterday.

The identity in question is:

NL = DEF + CAB

where, NL is the private sector net lending, DEF is the government’s deficit and CAB is the current account balance of payments (and is to a zeroth order approximation, exports less imports).

This is not a behavioural hypothesis but still a useful tool to build a narrative. Also, the causality connecting the identities is domestic demand and output at home and abroad.

Imagine, initially that NL is a small positive relative to GDP (for example, NL/GDP = 2%), Also remember that,

NL = Private Income − Private Expenditure

Now assume that private expenditure rises relative to private income. This will lead to higher GDP, a higher national income and a rise in imports because of income effects and hence a lower CAB. It will also lead to higher taxes because of higher income and hence will reduce the budget deficit, DEF, ceteris paribus.

So if the current account balance is in deficit, it would mean that the budget deficit and the current account deficit move in opposite directions.

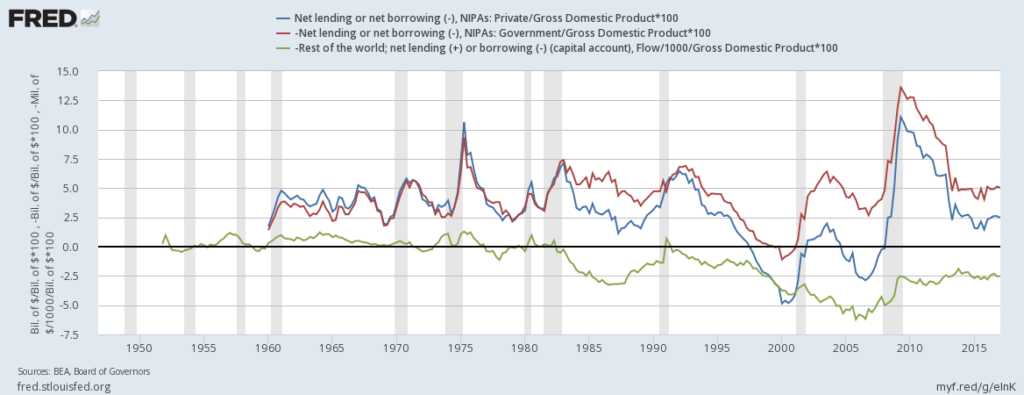

That’s the theoretical basis for the empirical relationship. But that in itself isn’t the whole story. This is because the other balance—net lending, NL—has a life of its own. As is the case in the United States and several western countries, it turned negative once or twice in the 1990s the 2000s, and when the private sector’s debt rose, it made a sharp U-turn into the positive territory. The blue line in this graph:

Click the graph to see it on FRED.

So, if net lending reverts to its mean of staying positive, one can then conclude that the cumulative budget deficit, or the public debt is affected by cumulative current account deficits.

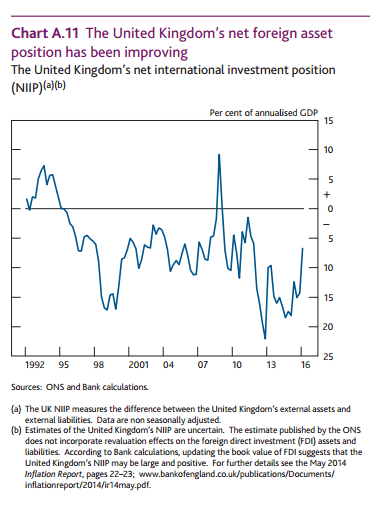

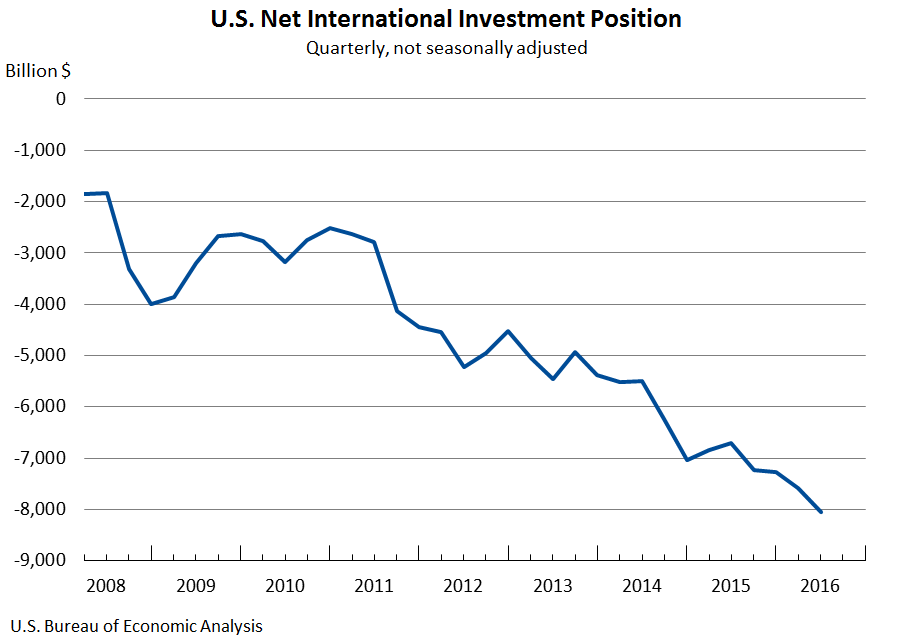

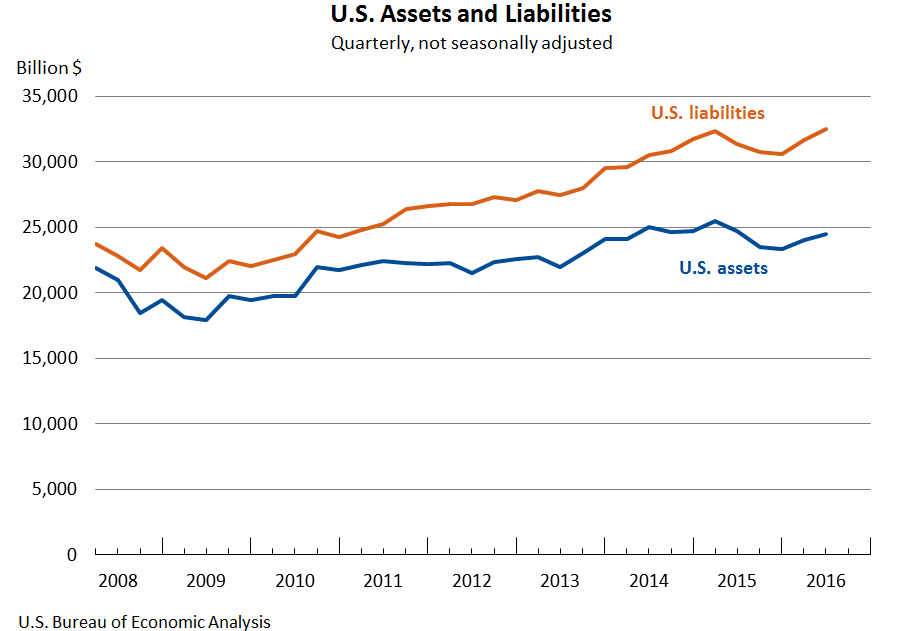

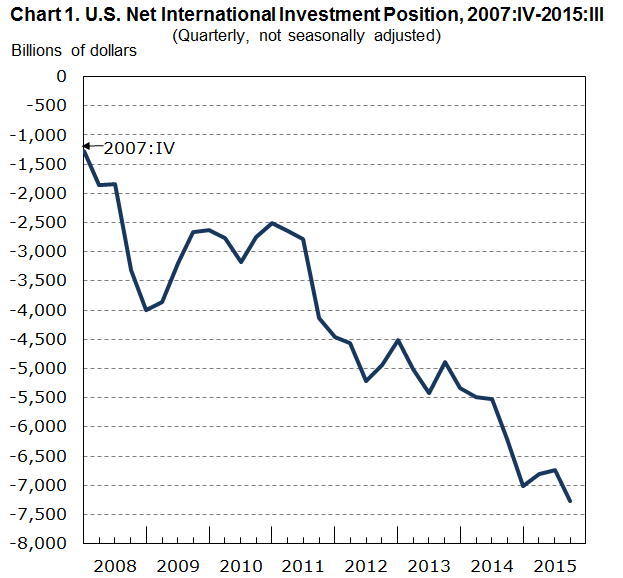

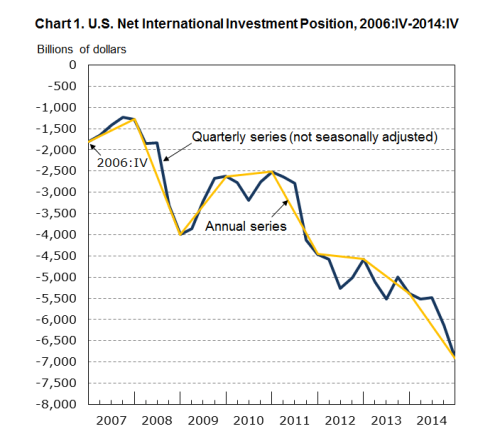

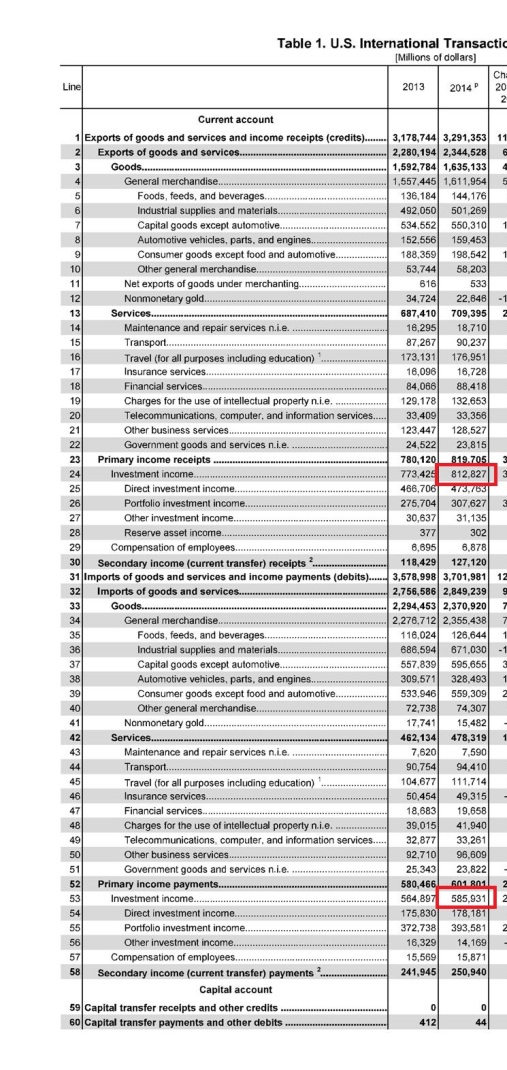

At any rate, the public debt shouldn’t be the main object of study. What’s more important is the international investment position. And it’s an identity that:

NIIP = cumulative CAB + Revaluations

where, NIIP, is the net international investment position.

A nation which runs current account deficits can become indebted to the rest of the world. IIP is the position of assets and liabilities of resident sectors of a nation. So, the net debt (the negative of NIIP) is the nation’s debt.

The above linked Econbrowser post brings in the complication of revaluations to deny the relationship between CAB and NIIP. But revaluations can’t save you for long.

In short, both public debt and NIIP depend on current account deficits.

Finally a weak analogy: if you play in the rain, you might enjoy it as well. But then if you get sick, you can’t say, “I felt so good playing in rains, so playing in the rain didn’t make me sick”. Saying the two deficits (current account and budget) move in opposite directions is an argument like that.