In recent posts on the Eurosystem, I looked at how it operates and in The Eurosystem: Part 2 highlighted how capital flow across borders within the Euro Area has led to a large accumulation of TARGET2 balances by some NCBs such as the Deutsche Bundesbank.

Bloomberg Businessweek had an article Germany’s Hidden Risk recently on this:

If the euro zone breaks into sorry little pieces, Germany could possibly lose its entire €495 billion claim. That’s more than $650 billion. It is 60 percent bigger than Germany’s annual federal budget—and larger than the lending under the European Financial Stability Facility and other aid programs that have received more scrutiny.

Some experts on TARGET2 disagree. So I got into an argument with a blogger (who has a good understanding of TARGET2, btw) according to whom

But let’s take a closer look. Who is this “Germany”? Will the German residents who got their accounts credited as a result of the Target2-facilitated transfers out of Ireland now lose their money? No. There will be no losses to private citizens. Despite all this misleading stuff about “enforced lending”, German citizens will be very grateful that they managed to repatriate their money to German via Target2.

So “Who is Germany”? Hidden in the above quote is that individuals and corporations only make Germany and that if the Euro collapses and hence the European Central Bank goes out of existence, Germany’s Bundesbank’s TARGET2 loss of €465bn (latest data I could get) will be not really a loss for “Germany”. This can be dismissed easily.

According to the IMF’s Balance Of Payments And International Investment Position Manual or BPM6

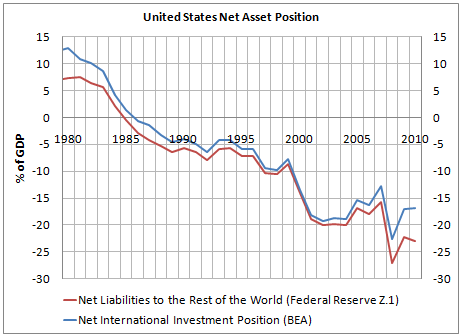

The IIP is a statistical statement that shows at a point in time the value of: financial assets of residents of an economy that are claims on nonresidents or are gold bullion held as reserve assets; and the liabilities of residents of an economy to nonresidents. The difference between the assets and liabilities is the net position in the IIP and represents either a net claim on or a net liability to the rest of the world.

A nation’s net wealth is the value of its real assets and its net international investment position. This definition has a Mercantalist bias but they have been proven right many times! A loss of Germany’s TARGET2 balance will represent a loss to Germany as a whole. Let us look at this closely with some real numbers.

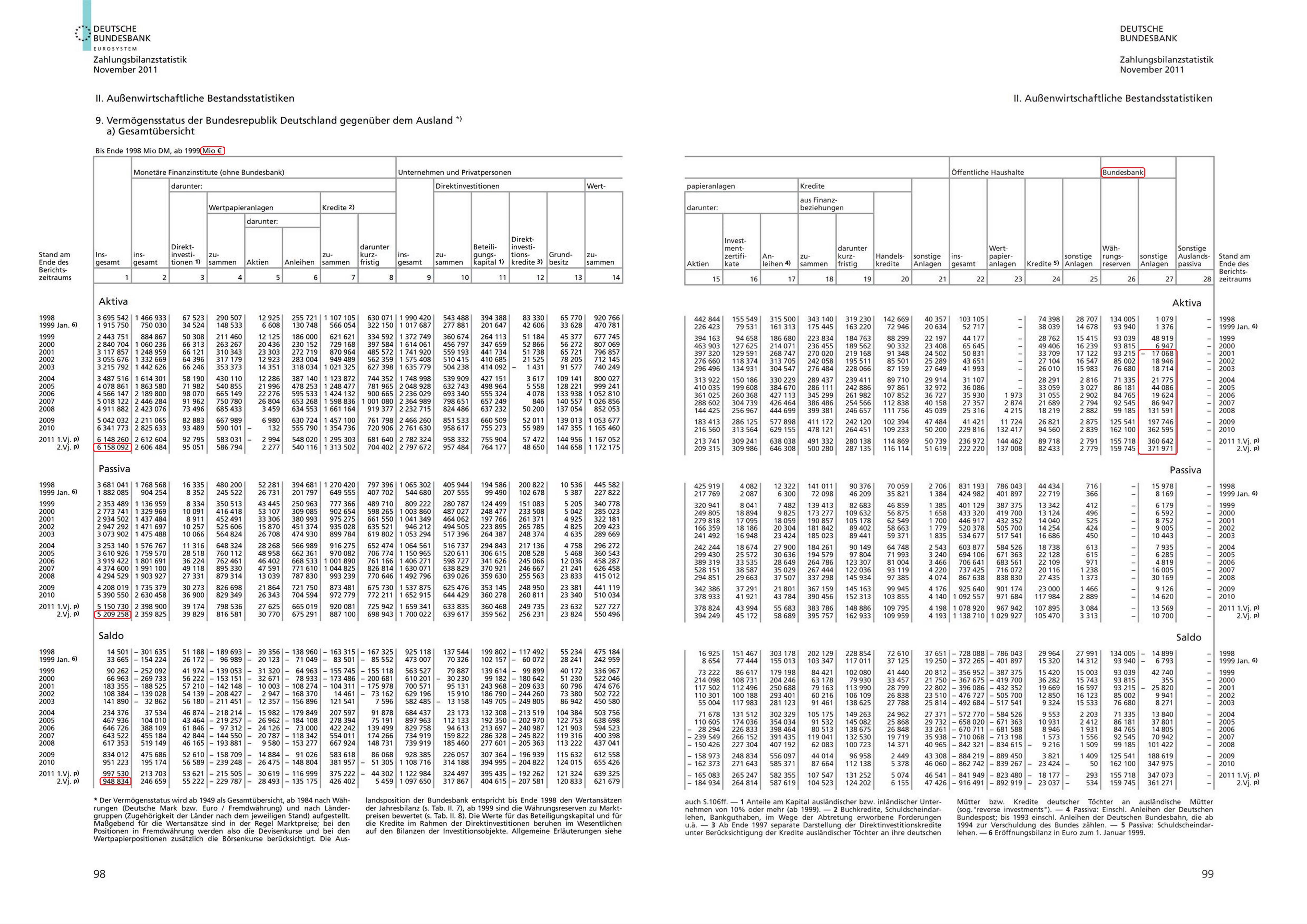

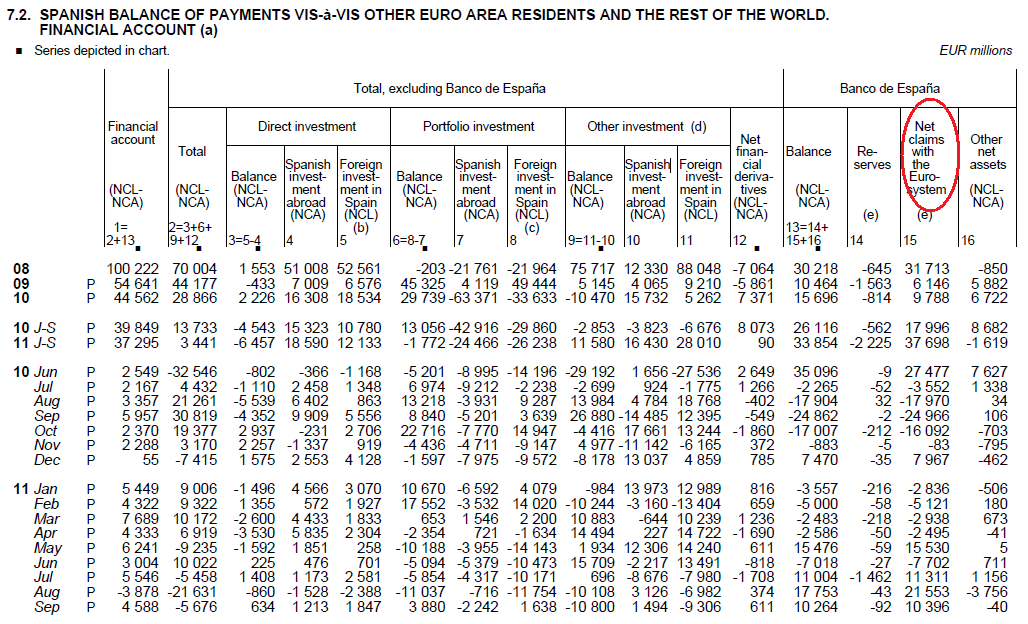

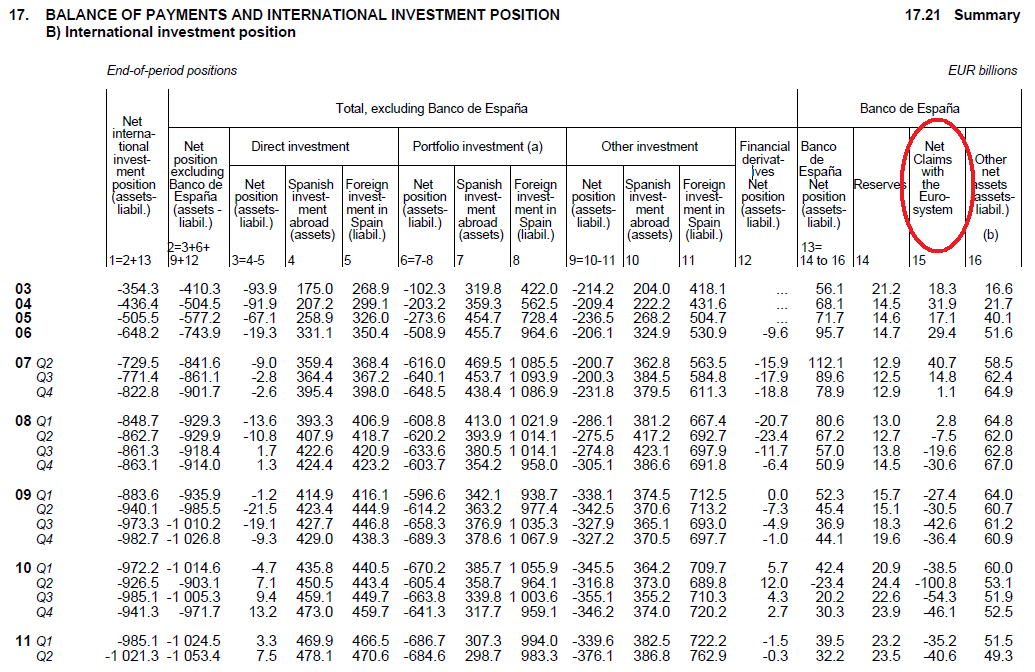

According to the Bundesbank’s Balance of Payments Statistics, November 2011, (with English translation below)

(click to enlarge)

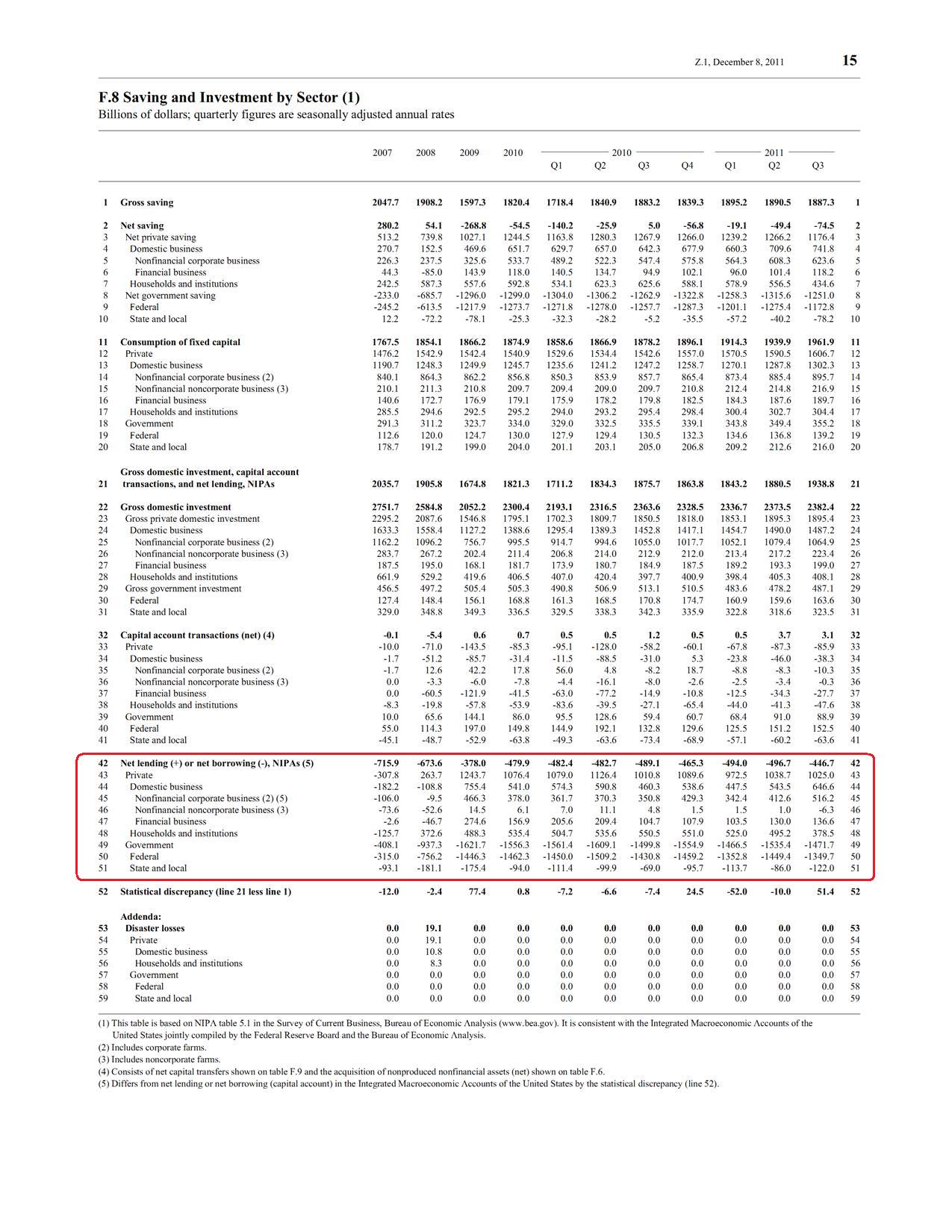

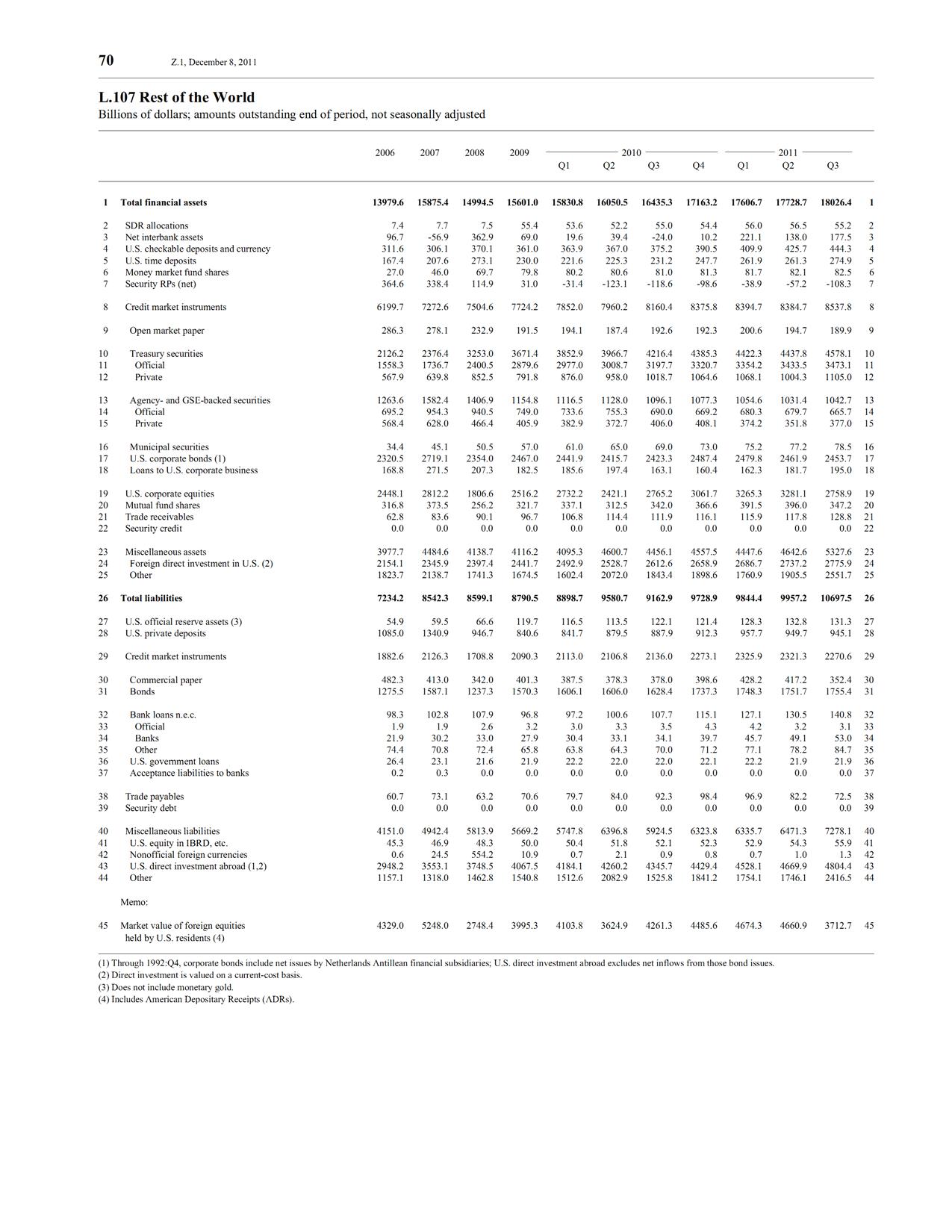

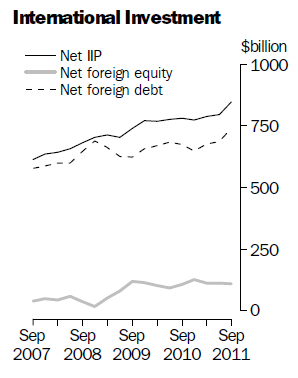

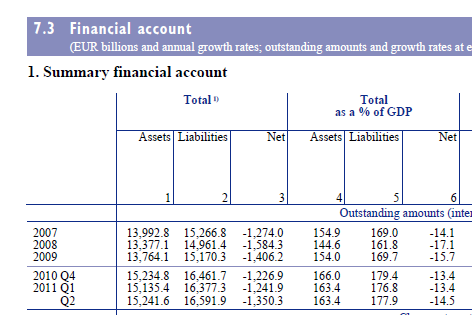

Germany had assets of €6,158bn and liabilities of €5,209bn and thus a net asset position of around €949bn.

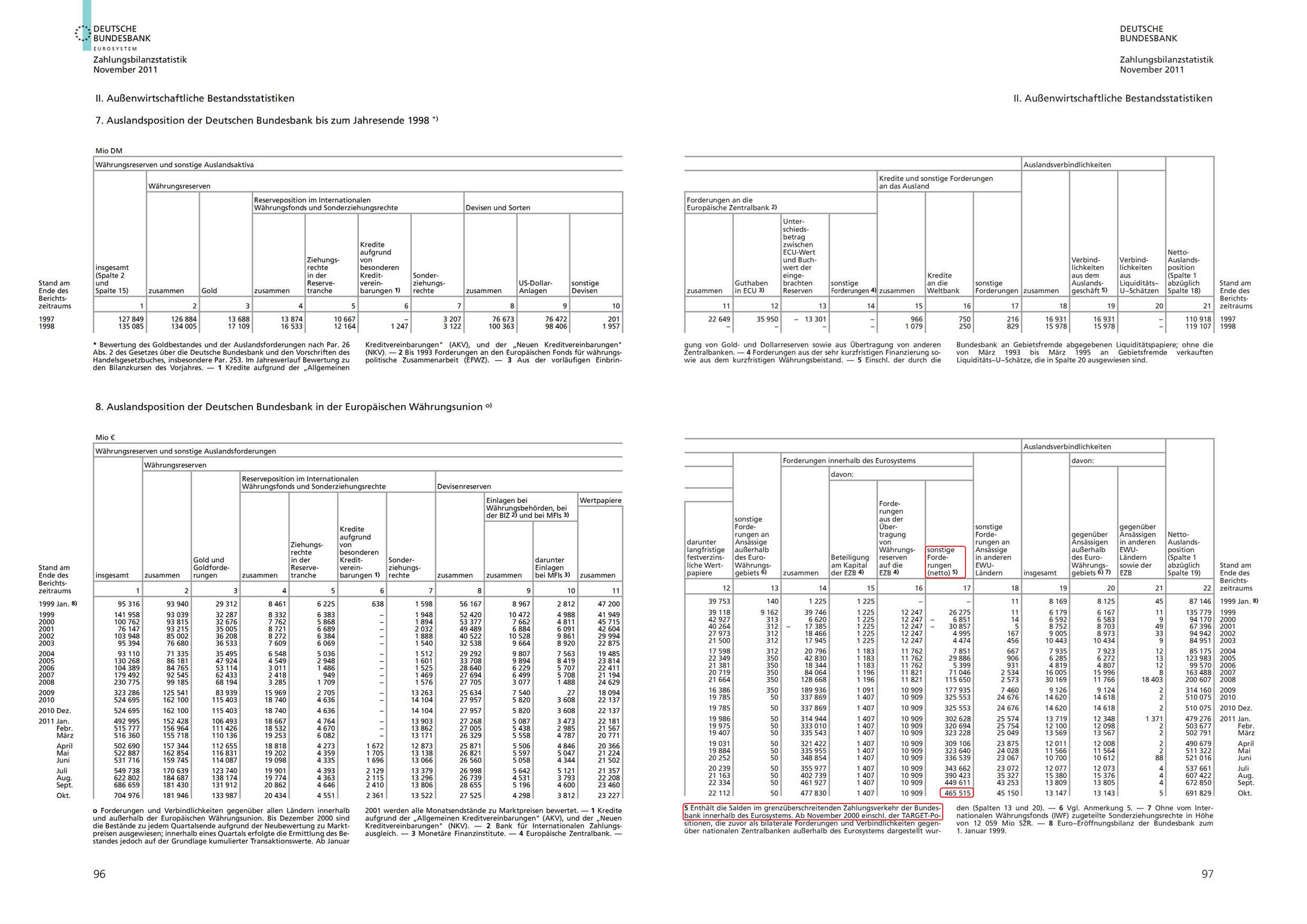

The table columns 26 and 27 show how Bundesbank’s foreign assets have increased recently but aren’t fully updated. Another table from the publication gives the updated numbers.

with the English translations:

So the Deutsche Bundesbank had a TARGET2 balance of €465bn at the end of October and is still rising! This is a sizable fraction of the net asset position of €949bn. (for other comparions, Germany’s 2010 GDP was €2,499bn).

The reason I went through this detail was to help the reader appreciate the question “Who is Germany”. Many breakup scenarios may put Germany at the risk of losing out this huge asset. No domestic transaction will bring this back to the original level.

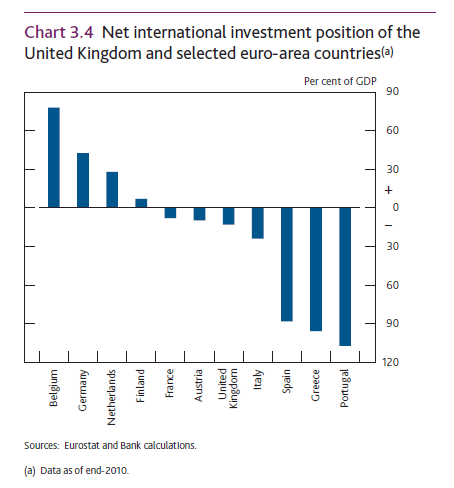

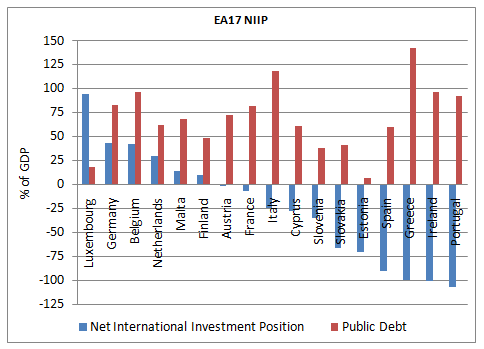

There are even more dreadful scenarios one can think of. A sudden loss of confidence and a dramatic “flight to quality” will lead residents and foreigners selling foreign assets in the Euro Area (in addition to non-Euro denominated assets) and shifting the liquidated deposits via TARGET2 to German banks and if Germany loses its TARGET2 balance, it could become a net debtor to the rest of the world!

An example will illustrate this. Suppose there is a further shift of €1,000bn before a Eurocalypse. This will lead to Germany’s gross assets increasing from €6,158bn to €7,158bn and liabilities from €5,209bn to €6,209bn, leaving the net position unchanged but increasing the Bundesbank’s TARGET2 position from €465bn to €1,465bn. A potential impairment of 100% implies that Germany’s Net International Investment Position is minus €516bn. All this ignoring residents’ revaluation losses of assets held abroad in such scenarios which will make the whole thing even more disastrous!

The above analysis is for non-residents inside the Euro Area making a financial flight to quality into Germany. For residents, a shift of say €1bn does not increase gross asset and liability positions – as far IIP construction is concerned – but increases Bundesbank’s TARGET2 assets by €1bn with the same effect as above.

In either case – residents or non-residents – Germany’s net asset position is under high risk because of the potential loss due to Bundesbank’s TARGET2 balance vanishing in thin air.

Of course, it won’t be an immediate risk to Germany in the sense that it can go back to the Deutsche Mark and redenominate debts in the new currency and do a fiscal expansion to prevent a loss in output. At any rate, Germany’s wealth which it earned in all these years would have reduced – a Mercantalist’s nightmare.