How did Keynes and the Cambridge Keynesians (such as Joan Robinson, Richard Kahn, Nicholas Kaldor and Wynne Godley) think the world economy works?

A few important principles relevant here and of course not exhaustive:

First, real demand, output and employment is determined by the fiscal and monetary policies of the government with the former having a more solid impact on demand. Second, fiscal policy has constraints due to the capacity to produce, and inflation. High inflation – although also influenced by demand – needs to to tackled by direct political means as it is also (highly) dependent on costs. Third, economies have a balance-of-payments constraint and a nation’s success depends crucially on how its producers perform in international markets.

For neoclassical economists and their cousins, world demand and output is determined by the supply-side. It is fantasized that with economic scarcity (as if!) utility and profit maximising behaviour of economic agents will lead to the most efficient allocation of resources and attempts to regulate trade will only make everyone worse-off. The amount of resources is “given” and interference with markets only leads to a lower output for that “given” amount of resources. Fiscal policy is neutral – although it is conceded by them that it can have positive short-term effect. Over the long run, fiscal policy is strictly neutral in this view. The prescription is for the government to balance the budget – sooner the better, and for monetary policy to either “control” the stock of monetary aggregates and/or for interest rate to return to some vaguely defined normal. Further, at an international level, the free trade ideology is imposed on nations because it is thought that it will lead to a convergence of incomes and living standards and full employment.

For example the WTO page on tariffs says:

Customs duties on merchandise imports are called tariffs. Tariffs give a price advantage to locally-produced goods over similar goods which are imported, and they raise revenues for governments. One result of the Uruguay Round was countries’ commitments to cut tariffs and to “bind” their customs duty rates to levels which are difficult to raise. The current negotiations under the Doha Agenda continue efforts in that direction in agriculture and non-agricultural market access.

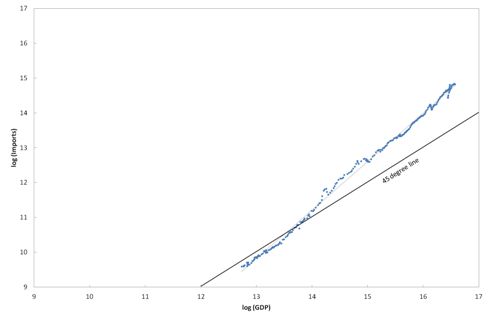

Unfortunately, free trade, has the opposite effect. Rather than leading to any convergence, it leads to some nations gaining more success and others failing. As Nicholas Kaldor said, “success breeds further success and failure begets more failure.”

How does this operate? A government which wishes its nation to grow faster can put up fiscal policy but sooner or later will be faced with a balance of payments because of the adverse effect on trade and rising indebtedness to foreigners. This constraint shows up as troubles in the foreign exchange markets. This constraint is strongest for a nation whose currency is fixed irrevocably (such as the Euro Area nations) but also is also strong for nations whose currencies are pegged and freely floating.

Now, a nation which has good exports sees good economic expansion via the “export multiplier”. Imports on the other hand are “leakages”. Let us think of a Nation X with a higher propensity to import. Faced with higher imports, X may try to use fiscal contraction to further contract demand and hence imports. This has negative ripples throughout the world as a whole. Exporters to X will see a lower demand for their products – even if they maintain market shares. Via lower multiplier than otherwise, this leads to a lower demand than otherwise in the rest of the world. This again has a contractionary effect on X because of lower exports again leading to a lower demand in the rest of the world than otherwise and so on. So fiscal expansion and investment are good for the world as a whole but free trade is damaging. This is not to deny the benefits of globalization but a world with free trade will be worse-off than with a system of regulated trade which will have higher output, income and world trade since allows more space for fiscal policy and via an accelerator process, allows investment to expand faster.

Now, till recently the United States was acting as the “demander of the last resort” because of its huge imports. Faced with a high balance of payments deficit (in the current account), the United States neither wants to be in this position nor is going to expand domestic demand. It is as if the engine of growth has been cut off.

Faced with so many constraints, nations try to play the beggar-my-neighbour game. Unfortunately this game is also played by the creditor nations. The phrase was first introduced by Joan Robinson in a 1937 article titled Beggar-My-Neighbour Remedies For Unemployment. This excerpt is from beginning of the article:

For any one country an increase in the balance of trade is equivalent to an increase in investment and normally leads (given the level of home investment) to an increase in employment.1 An expansion of export industries, or of home industries rival to imports, causes a primary increase in employment, while the expenditure of additional incomes earned in these industries leads, in so far as it falls upon home-produced goods, to a secondary increase in employment. But an increase in employment brought about in this way is of a totally different nature from an increase due to home investment. For an increase in home investment brings about a net increase in employment for the world as a whole, while an increase in the balance of trade of one country at best leaves the level of employment for the world as a whole unaffected.2 A decline in the imports of one country is a decline in the exports or other countries, and the balance of trade for the world as a whole is always equal to zero.3

In times of general unemployment a game of beggar-my-neighbour is played between the nations, each one endeavouring to throw a larger share of the burden upon the others. As soon as one succeeds in increasing its trade balance at the expense of the rest, others retaliate, and the total volume of international trade sinks continuously, relatively to the total volume of world activity. Political, strategic and sentimental considerations add fuel to the fire, and the flames of economic nationalism blaze ever higher and higher.

In the process not only is the efficiency of world production impaired by the sacrifice of international division of labour, but the total of world activity is also likely to be reduced. For while an increase in the balance of trade of one country creates a situation in which its home rate of interest tends to fall, the corresponding reduction in the balances of the rest tends to raise their rates of interest, and owing to the apprehensive and cautious tradition which dominates the policy or monetary authorities, they are chronically more inclined to foster a rise in the rate of interest when the balance of trade is reduced than to permit a fall when it is increased. The beggar-my-neighbour game is therefore likely to be accompanied by a rise in the rate of interest for the world as a whole and consequently by a decline in world activity.

The principal devices by which the balance of trade can be increased are (1) exchange depreciation, (2) reductions in wages (which may take the form of increasing hours ot work at the same weekly wage), (3) subsidies to exports and (4) restriction of imports by means of tariffs and quotas. To borrow a trope from Mr. D. H. Robertson, there are four suits in the pack, and a trick can be taken by playing a higher card out of any suit.

1 See below, p. 159, note, for an exceptional case. [Note on p. 159: When the foreign demand is inelastic a tax on exports (as in Germany in 1922) or restriction of output (as in many raw-material-producing countries in recent years) will increase the balance of trade, while at the same time reducing the amount of employment in the export industries, and increasing the ratio of profits to wages in them. In these circumstances, therefore, an induced increase in the balance of trade may be accomoanied bv no increase, or even a decrease, in the level of employment.]

2 Unless it happens that the Multiplier is higher than the average for the world in the country whose balance increases.

3 The visible balances of all countries normally add up to a negative figure, since exports are reckoned f.o.b. and imports c.i.f. But this is compensated by a corresponding item in the invisible account, representing shipping and handling costs.