The question is wrong 🤡

It’s commonly claimed by the opponents of neochartalism or “modern monetary theory” or “MMT”, that the theory advocates the use of “money-financed deficits” or “printing money”—the lowbrow language. This claim is because of a poor understanding of the theory and I say this as a critic. Many Post-Keynesians who don’t identify as chartalists also keep spreading this. Of course this isn’t the complete story as the neochartalists themselves create this confusion indirectly/unknowingly about their own theory.

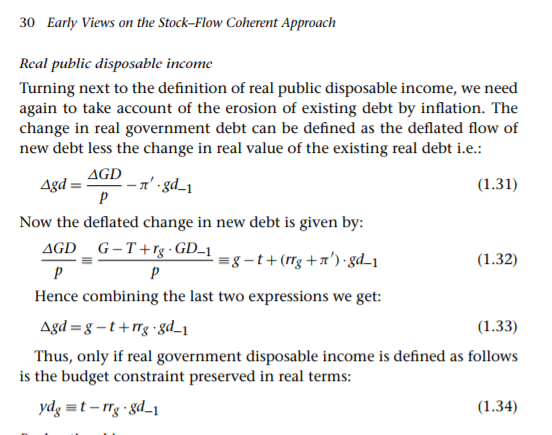

Imagine a financial system such as in Canada where banks have zero reserve requirements and little bank settlement balances/reserves outside crises. The government can expand fiscal policy by simply raising government expenditure. You could think of the deficit in one period/year as “endogenous”, which will depend on how much taxes come in, which in turn depends on how the private sector responds to the stimulus (with complications of international trade). The difference between the two will be the “net borrowing” in the language of national accounts. If there’s a surplus, the government would be a net lender. But let’s assume it’s in deficit. The government has an account at the Bank of Canada and it will make this shortfall by issuing debt.

The private sector would have additional income and wealth because of the stimulus and the borrowing. Because: the stimulus would raise output and income of the private sector and also because the very act of deficit also adds to the private sector wealth.

Banks would lend more because of the rise in output would lead to more demand for loans, the central bank has a large control of the interest rates and could even set the whole yield curve. There’s no crowding out and the reserve requirement is zero! Banks would also also have more income and their capital-adequacy would improve to allow them to lend more.

Loans make deposits and in the aggregate they won’t be constrained really in lending although individual banks would need to fund themselves as not raising would cause them to have large overdrafts at the Bank of Canada, the central bank and they might run out of collateral to post at the central bank.

The private sector would decide how much of its wealth it wants to allocate in banknotes and how much in government bonds and other financial assets. If the private sector wants more banknotes, they’ll ask their banks which in turn would obtain from the Bank of Canada by going in an overdraft. The Bank of Canada would buy government bonds in the financial markets and bring the reserves back to zero from negative.

In other words, the amount of banknotes and government bonds that the private sector wishes to hold is entirely decided by the private sector. The phrase “money-financed deficits” implies that the Canadian government and the Bank of Canada decide how much this is and is misleading.

Anything here is a typical story in neochartalism. Although neochartalist would like to go more such as proposing “no-bonds” with all deficit spending from the beginning of time to be reflected in banks’ settlement balances at the Bank of Canada, it’s not like a strict requirement that neochartalism would only work with zero-bonds. They’d be comparatively happy with more fiscal expansion than no expansion or contraction or an expansion which is not much.

The main reason for the stimulus and the rise in output would be the act of increased spending of the government itself. Money vs. bonds decided by the private sector needs.

The reason neochartalists’ claim sound like “printing-money” in the lowbrow language is that the above dynamics is poorly understood by their opponents, because monetarism is a prejudice which affects almost everyone.

But to complicate that’s not all. There’s a Stephanie Kelton paper with the title Can Taxes And Bonds Finance Government Spending?

This misleads the reader into thinking that neochartalists are advocating “printing money” but the arguments above show how misleading the phrase itself is. What the “MMTers” are saying is that the government has a virtually large borrowing ability. The phrase “borrowing” makes us thinking that there is some sort of intrinsic constraint. Hence their rejection of the word “borrowing”.

To prove all this, neochartalists try to draw long T-accounts so that the reader is convinced that everything is fine, government deficit is actually mirrored as private sector deficit, the mechanics of central banking in trying to prove in detail how the government can raise as much funds as it wants, so that the reader is convinced there’s no hanky-panky.

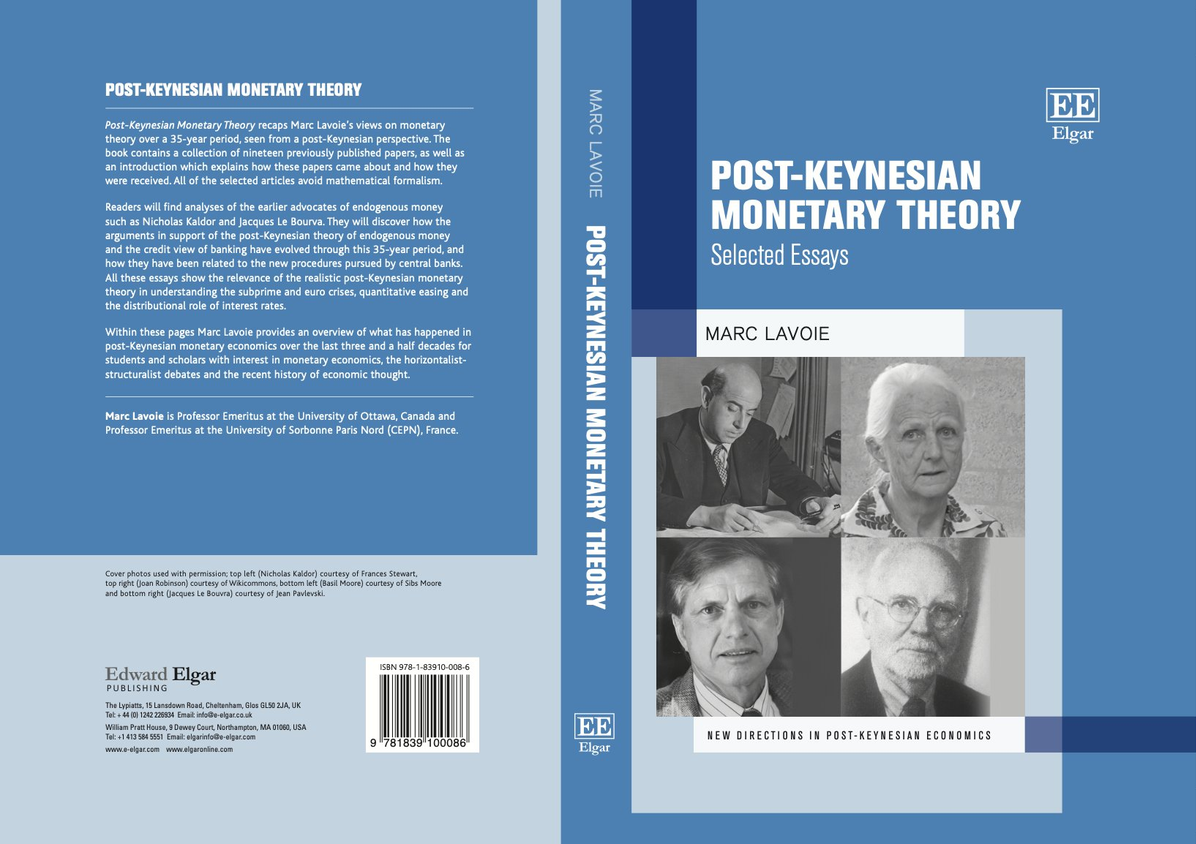

But in an effort to prove that they go into overkill. So for example, typically governments can’t have overdrafts at their central bank because neoliberals have made this the law to “discipline” the government. So some positive critics such as Marc Lavoie would try to constructively critique them in a friendly way but others would simply dismiss them using this as an excuse. Neochartalists would respond to former saying that it still doesn’t constrain the government which is true but it’s not a perfect argument.

And in all this they also end up claiming horribly wrong things that taxes needn’t be increased. That is unfortunate as it gives their opponents an even bigger chance to dismiss them. Some like me have criticised them for this too but “MMT” has kind of become this catch-phrase for everything Post-Keynesian so the ones with bad faith exploit it to dismiss the whole of Post-Keynesianism.

More than that, the story falls short because in the case of open economy, the government has constraints, brought because of historic reasons causing large differences in competitiveness between nations. Trade imbalances can cause fiscal policy to be constrained and the international investment position to be unsustainable.

But this part is a digression for this post. The main point is that the claim that “MMT advocates printing money” is a lowbrow claim.