… But more disturbing still is the notion that with a common currency the ‘balance or payments problem’ is eliminated and therefore that individual countries are relieved of the need to pay for their imports with exports.

Quite the reverse: the existence or a common currency makes a country more directly dependent on its ability to sell exports and import substitutes than it was before, particularly as it will then possess no means whereby it can (in the broadest sense) protect itself against failure.

– Wynne Godley, Commonsense Route To A Common Europe, in The Observer, 6 January 1991.

Greece had large negative current account balance of payments and Germany had the opposite over the lifetime of the Euro.

Yet, there are some economists who argue that the Euro Area crisis is not a balance of payment crisis. Of course there are other aspects to the crisis as well but this in my view is the main issue. There was a debate between Sergio Cesaratto and Marc Lavoie on this. Now there is a new paper in the most recent issue of ROKE (Review of Keynesian Economics) by Eladio Febrero, Jorge Uxó and Fernando Bermejo which discusses this. The Wayback Machine/Internet Archive link is here if you are reading it after the journal puts the paywall again.

The authors seem to be against Sergio Cesaratto view. Since I agree with Cesaratto, I thought I should comment on it.

The fundamental problem of the Euro Area is that it doesn’t have a central government. If there had been a central government like the US federal government, with large fiscal powers, the Euro Area crisis would have been far less deeper. This is because weaker regions would have been recipients of “fiscal transfers”, i.e., receive more government expenditure than what they send in taxes.

Fiscal transfers can be seen transactions in the balance of payments of Euro Area countries if the EA had a central government. The way to do balance of payments for monetary and political unions is explained in the IMF Balance of Payments and International Investment Position manual. Take a country like Greece. The Euro Area government would be considered external to Greece. Same for other countries. But for the Euro Area as a whole, the central government would be considered inside the Euro Area.

So government expenditure would appear in Greek exports in the goods and services account and transfers in the secondary income account. Taxes would appear only in the latter.

So there is an improvement in the current account balance of payments for regions compared to the case when there is no central government. Current account balances accumulate to the net international investment of the whole country. A country which has persistent imbalances would have negative net international investment position, i.e., indebtedness to other countries.

So fiscal transfers keep all this in check by improving the current account balance. So if the Euro Area had a central government, debts of a country like Greece would be in check.

By joining the half-baked half-way house, Greece got an overvalued exchange rate and easier access for other Euro Area countries into its markets and its external imbalances worsened in its lifetime inside the monetary union.

Nations with high current account deficits will also have higher public debt than otherwise and would need international investors to buy the debt which residents won’t. Normally the price would adjust to bring international investors but as we have seen, sometimes there is no price and a fall in bond prices might lead to expectations of further fall leading external investors to dump the bonds instead of finding them attractive.

The trouble with Febrero et al. is that they seem to think that the European central bank can purchase all government debt of nation. Certainly, the European Central Bank (ECB) has stepped in at various times to ease the pressure on government bond markets. But the trouble with this is that there are under some conditions such as assuming it can impose tight fiscal policy on the governments it is helping.

If the Euro Area treaty is modified to allow countries to have independent fiscal policies, then for stability, the ECB has to buy bonds without limits and can keep accumulating. It is a political mess. A country like Germany could argue that it is writing an open cheque to Greece.

A political union wouldn’t have such problems. National level governments such as the Greek government would have fiscal rules on them, and hopefully not the supranational government. This is like the United States where state governments have rules on their budgets.

In contrast, if the ECB guarantees Greece’s debt, it has to impose some rules and since Greece is not recipient of any equalisation payments—the fiscal transfers—its performance is still dependent on its competitiveness. This is because competitiveness would affect the Greece government’s fiscal balance and hence put a deflationary pressure on Greece’s fiscal stance.

On the other hand, a Euro Area with a central government would imply Greece is recipient of substantial equalisation payments and its competitiveness isn’t so binding.

An argument of the economists arguing that the European monetary system has this thing called TARGET2 and that the intra-Eurosystem balances (i.e., automatic credits offered by one national central bank to another) can rise without limit is used in this paper. This is highly misleading. It is true but one should look at the changes in debits and credits elsewhere. Suppose a country like Greece sees a large private financial outflow. While T2 can absorb a lot of this—much more than anyone imagined—in the late stages, Greece banks become heavily indebted to their national central bank, The Bank of Greece. When they run out of collateral, the rules under ELA, Emergency Liquidity Assistance, is triggered. So TARGET2 or more accurately the Eurosystem cannot absorb everything.

In summary, the Euro Area cannot do without a central government in the long run. Anyone who thinks that the ECB or the Eurosystem can buy whatever residual debt private investors doesn’t understand that in such a system, Euro Area governments are given an open cheque.

The difference between not having a central government and a central government is that in the former, there is no equivalent income flow as in the latter. The Eurosystem purchases would affect the financial account of balance of payments, not the current account.

One of the noticeable assertions of the paper is:

With T2, there is just one currency. This means that if foreign exchange markets did not exist, there could not be a BoP crisis, so that the cause of the crisis should be found elsewhere.

The trouble with this is that it sees it only as a currency crisis. But the fact is that countries whose external position were weak were the ones running into trouble in the Euro Area. Had current account deficits not blown up, countries would have had better fiscal balance since the current account balance and the budget balance are related by an identity and even behaviourally as can be seen in stock-flow consistent models. In crisis times, foreign investors are more likely to shift their funds in their home countries. With better balance of payments, public debt would be held more internally and there would have been less pressure on government bonds.

There are comments in the paper about too much credit etc. This is true, but then the Euro Area crisis would have looked more like the economic and financial crisis affected the United States.

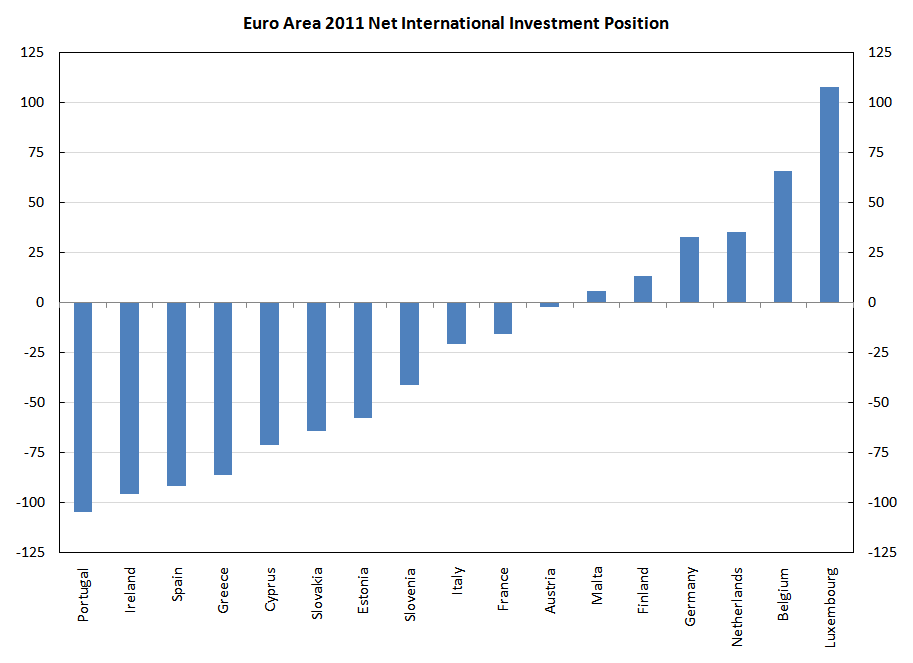

Here’s the the NIIP of Euro Area countries in 2011.

Doesn’t this explain why Germany was in a better position than Greece when the crisis started heating up? Or that Netherlands was in a better position than Portugal?