This is a nice interview of Marc Lavoie with Marshall Auerback organized by the Institute for New Economic Thinking (INET) in which he talks mainly about his new book Post-Keynesian Economics: New Foundations.

Tag Archives: marc lavoie

Sergio Cesaratto’s Debate With Marc Lavoie On Whether The Euro Area Crisis Is A Balance-Of-Payments Crisis – II

This is a continuation of the post from the end of 2014, although reading that isn’t necessary.

In a new paper, Marc Lavoie continues his debate with Sergio Cesaratto on whether the Euro Area crisis is a balance-of-payments crisis or not. For the sake of completeness, here’s the list of papers, with references copy-pasted from Marc’s latest paper. Not all links are final versions and some may not be available to read in full).

- Cesaratto, S. 2013. “The Implications of TARGET2 in the European Balance of payments Crisis and Beyond.” European Journal of Economics and Economic Policy: Intervention 10, no. 3: 359–382. link

- Lavoie, M. 2015. “The Eurozone: Similarities to and Differences from Keynes’s Plan.” International Journal of Political Economy 44, no. 1 (Spring): 3–17. link

- Cesaratto, S. 2015. “Balance of Payments or Monetary Sovereignty?. In Search of the EMU’s Original Sin–Comments on Marc Lavoie’s The Eurozone: Similarities to and Differences from Keynes’s Plan.” International Journal of Political Economy 44, no. 2: 142–156. link

- Lavoie, M. 2015. “The Eurozone Crisis: A Balance-of-Payments Problem or a Crisis Due to a Flawed Monetary Design?” International Journal of Political Economy 44, no. 2: 157-160. (abstract)

As mentioned in my part 1, referred to on top of this post, I agree with Sergio Cesaratto.

Sergio Cesaratto with Marc Lavoie (picture credit: Matias Vernengo)

Sergio Cesaratto with Marc Lavoie (picture credit: Matias Vernengo)

Marc Lavoie’s main point in the final paper seems to be that, “Eurozone countries can never run out of TARGET2 balances, which can take unlimited negative values, so that the evolution of the balance of payments cannot be the source of the crisis”.

This is not accurate in my view. Although the rules of the Eurosystem allow unlimited and uncollateralized credit facility between the Euro Area NCBs and the ECB, one has to look at the counterpart to the T2 imbalances. If an economic unit transfers funds across border from country A to country B, this first results in a reduction of balances of banks in country A at their NCB and may result in an intraday overdraft (“daylight overdraft” in U.S. language), usage of the marginal lending facility with the NCB, an MRO, or an LTRO and finally ELA in late stages of a crisis (if capital outflow is large).

Marc himself mentions this point in his latest paper:

If a Eurozone country is running a current account deficit that banks from other Eurozone members decline to finance, or if it is subjected to capital outflows, then all that happens is that the national central bank of that country will be accumulating TARGET2 debit balances at the ECB. There is no legal limit to these debit balances. The national central bank with the debit balances, which pay interest at the target interest rate, has as a counterpart in its assets the advances that it must make to its national commercial banks at that same target interest rate. And the commercial banks can obtain central bank advances as long as they show proper collateral. Why would the size of current account deficits or TARGET2 debit balances worry speculators? There might be a problem with the quality of the loans that have been granted by the banks, or with the size of the government debt, but that as such has nothing directly to do with a balance-of-payments problem.

[italics: mine]

But that is the case! It’s because of balance-of-payments. Nations who had high indebtedness to the rest of the Euro Area saw more capital flight. This is because in times of crisis, there is a home bias and international investors are likely to sell securities abroad and repatriate funds home. Large current account imbalances lead to a large negative net international investment position. (It’s of course also true that revaluations are important, and this is what happened in the case of Ireland). So when non-residents sell securities to domestic investors, banks are likely to get into a bad situation because they have to accommodate these transfer of funds and are losing central bank balances on a large scale.

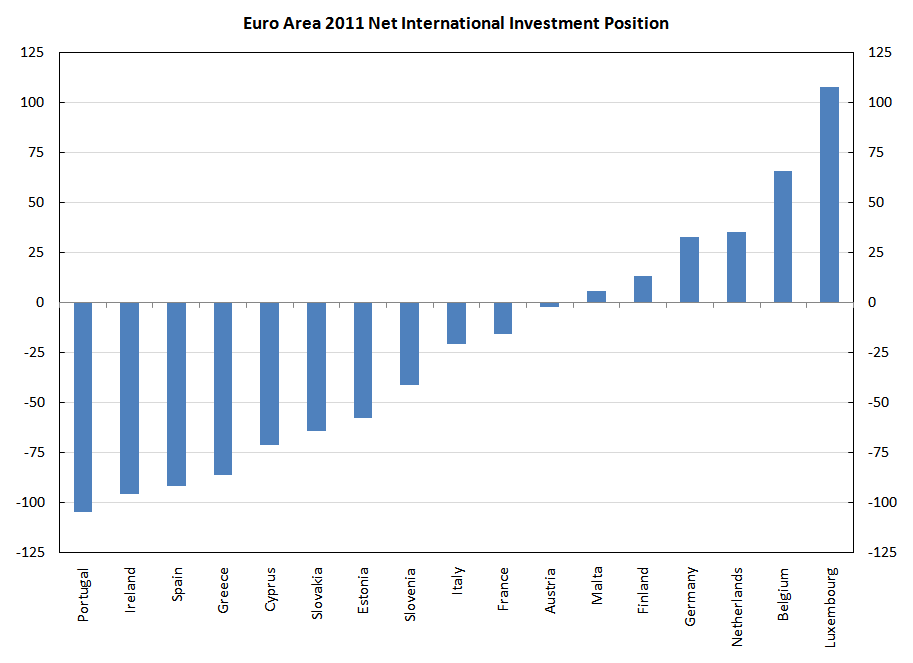

It is precisely nations which had worse net international investment positions which were affected as charted in my previous post on this.

Now moving on to definitions: what is a balance-of-payments problem? The simplest definition is the problem for residents in obtaining finance from non-residents. Greece precisely has been struggling to obtain funds from non-residents.

So I do not agree with Marc’s view that:

Cesaratto, as others, is adamant that the Eurozone crisis is a balance-of-payments crisis, whereas I believe, as others do, that this is a side issue.

Marc Lavoie also says that the people arguing for this view are implicitly assuming some kind of “excess saving” view on all this:

In discussions with colleagues who support a “current account deficit” view of the Eurozone crisis, I sometimes get the impression that they are also endorsing a kind of “excess saving” view of the economy. They tell me that current accounts deficits are unsustainable within the Eurozone because the core Eurozone countries will refuse to lend to the periphery and will thus prevent these countries from financing economic activity. This seems wrong to me.

I disagree with this. It’s precisely because residents’ liabilities are large compared to their financial assets that they have to rely on non-residents/foreigners. And during the crisis a lot of capital outflow has happened and this precisely shows that non-resident private investors are unwilling to lend again on the same scale as before. This obviously means that to obtain finance, governments of nations affected have to take the help of the official sector abroad, such as from governments, the ECB and the IMF. If TARGET2 alone could do the trick, is the Greek government foolish to go abroad?

It is of course true that the design of the Euro Area was faulty. But that still leaves open the question about why Germany is not facing a crisis as severe as Greece. The design view cannot explain this. Any country (or all countries) in the Euro Area could have faced a crisis. There is a pattern here and that is where balance-of-payments comes in.

This debate is an interesting one. Both Sergio Cesaratto and Marc Lavoie agree on almost everything, except this BIG thing.

Of course this also spills over to policy proposals. Marc Lavoie believes that the European Central Bank can guarantee that all nations can have independent fiscal policies (by promising to buy all government debt which the financial markets isn’t interested in purchasing). Sergio Cesaratto is clear on this (and I agree very much) – in another paper Alternative Interpretation of a Stateless Currency Crisis:

A more resolute role of the ECB as lender of last resort accompanied by fine-tuned expansionary fiscal policies can only be imagined in a different political and institutional framework, quite close to that of a political union.

Let’s consider what happens if there is no federal government and if the ECB is the main supranational authority (ignoring other supranational institutions which have limited powers). Suppose the ECB were to guarantee the debt of governments of all Euro Area nations. There’s nothing to prevent, say, the government of Finland to increase the compensation of its employees every year by a huge percentage and thereby affecting Finnish corporations’ compensation of its employees. This will result in a reduction of competitiveness of Finnish producers and Finnish resident economic units will rely more on goods and services produced abroad. This will raise Finland’s net indebtedness to the rest of the Euro Area and the world. If someone believes that this debt is not a problem, how about the inflationary impact of this rise in demand on the rest of the Euro Area?

So the solution lies in bringing down the balance-of-payments imbalances (both negative and positive ones such as that of Germany). This requires a supranational institution, which is a central government. National governments would have rules on their budgets but the central government — since its goals and objectives are different — wouldn’t be bound by any rules. Wage rises would need to be coordinated. And as I argue in this post, fiscal transfers also plays a role of keeping imbalances in check.

Of course there are many other economists who also argue that the Euro Area problem is a balance-of-payments problem, but with a different motive. Their argument is to blame the nations in crisis instead of taking a humanist approach.

To summarize, the Euro Area problem wouldn’t have been a balance-of-payments problem had the official sector promised to act as a lender of the last resort to national Euro Area governments without any condition. As long as there are conditions, it is a balance-of-payments problem. One cannot pretend that the European Central Bank has or can be given such powers to lend without any condition. And hence the Euro Area crisis is a balance-of-payments problem.

Ben Bernanke Embracing Heterodox Ideas

It’s remarkable how some economists were ahead of the time, while others such as Ben Bernanke seem to just catch up. In a recent post on his blog Ben Bernanke gives out some unorthodox ideas to resolve the Euro Area crisis.

Ben Bernanke says:

… Germany’s large trade surplus puts all the burden of adjustment on countries with trade deficits, who must undergo painful deflation of wages and other costs to become more competitive. Germany could help restore balance within the euro zone and raise the currency area’s overall pace of growth by increasing spending at home, through measures like increasing investment in infrastructure, pushing for wage increases for German workers (to raise domestic consumption), and engaging in structural reforms to encourage more domestic demand. Such measures would entail little or no short-run sacrifice for Germans, and they would serve the country’s longer-term interests by reducing the risks of eventual euro breakup.

…

Second, it’s time for the leaders of the euro zone to address the problem of large and sustained trade imbalances (either surpluses or deficits), which, in a fixed-exchange-rate system like the euro zone, impose significant costs and risks. For example, the Stability and Growth Pact, which imposes rules and penalties with the goal of limiting fiscal deficits, could be extended to reference trade imbalances as well. Simply recognizing officially that creditor as well as debtor countries have an obligation to adjust over time (through fiscal and structural measures, for example) would be an important step in the right direction.

That’s in 2015.

Compare that to the conclusion from a 2007 paper titled A Simple Model Of Three Economies With Two Currencies: The Eurozone And The USA written by Wynne Godley and Marc Lavoie for Cambridge Journal Of Economics (journal link):

… it should be noted that balanced fiscal and external positions for all could as well be reached if the euro country benefiting from a (quasi) twin surplus as a result of the negative external shock on the other euro country decided to increase its government expenditures, in an effort to get rid of its budget surplus. This case, where the surplus countries rather than the deficit countries adjust, as many authors have underlined, would eliminate the current downward bias in worldwide economic activity. Now this would require an entirely new attitude towards government deficits. One would need an anti-Maastricht approach, that would run against the Stability and Growth Pact and its neoliberal obsession with fiscal balance and government debt reduction. For instance, one would need a new Pact, that would discourage fiscal surpluses. National governments that ran budget surpluses would pay large proportional automatic levies to the European Union, who would be compelled to spend the sums thus collected in the deficit countries. In this manner, the ‘weak’ and the ‘strong’ members of the eurozone could converge towards a super-stationary state, with balanced budgets and current accounts, through an increase rather than a decrease in government expenditures and economic activity.

Alternatively, the present structure of the European Union would need to be modified, giving far more spending and taxing power to the European Union Parliament, transforming it into a bona fide federal government that would be able to engage into substantial equalisation payments which would automatically transfer fiscal resources from the more successful to the less successful members of the euro zone. In this manner, the eurozone would be provided with a mechanism that would reduce the present bias towards downward fiscal adjustments of the deficit countries. This raises the profound question as to whether in the long term it is possible to have a community of nations which have a single currency which does not have a federal budget of substantial size, and by implication a federal government to run it—a point that was made very early on in Godley (1992).

[italics in original]

Sergio Cesaratto’s Debate With Marc Lavoie On Whether The Euro Area Crisis Is A Balance-Of-Payments Crisis

Sergio Cesaratto has a new paper Balance Of Payments Or Monetary Sovereignty? In Search Of The EMU’s Original Sin – A Reply To Lavoie. (html link, pdf link)

I obviously agree with Sergio Cesaratto.

As long as there is no supranational fiscal authority, a Euro Area nation’s economic success is more restricted by its exports than otherwise as there is no mechanism for fiscal transfers. The European Central bank can of course backstop and to some extent it has done so, but it cannot let fiscal policy of nations become independent of balance of payments beyond a certain extent. If it does so, nations’ public debt will rise together with net indebtedness to foreigners relative to output and this will become unsustainable. The European Central Bank (the Eurosystem less the domestic National Central Bank) will become a huge creditor and this will not be acceptable to the rest of the Euro Area. (There is of course the question whether this would be morally right but I do not think it is immoral beyond a limit).

To some extent, Mario Draghi has acted the opposite and pushed austerity, but one cannot assume unlimited power for the ECB (Eurosystem to be precise).

The other way to check that it is indeed a balance-of-payments crisis is to simply see the net international investment position of nations. This chart is from 2011 (intentionally chosen to be old).

The nations troubled most had huge net indebtedness to foreigners. If it is not a balance-of-payments crisis, how does one explain that countries such Germany and Luxembourg had far less troubles than Greece and Portugal?

Abstract of the paper:

In a recent paper Marc Lavoie (2014) has criticized my interpretation of the Eurozone (EZ) crisis as a balance of payments crisis (BoP view for short). He rather identified the original sin “in the setup and self-imposed constraint of the European Central Bank”. This is defined here as the monetary sovereignty view. This view belongs to a more general view that see the source of the EZ troubles in its imperfect institutional design. According to the (prevailing) BoP view, supported with different shades by a variety of economists from the conservative Sinn to the progressive Frenkel, the original sin is in the current account (CA) imbalances brought about by the abandonment of exchange rate adjustments and in the inducement to peripheral countries to get indebted with core countries. An increasing number of economists would add the German neo-mercantilist policies as an aggravating factor. While the BoP crisis appears as a fact, a better institutional design would perhaps have avoided the worse aspects of the current crisis and permitted a more effective action by the ECB. Leaving aside the political unfeasibility of a more progressive institutional set up, it is doubtful that this would fix the structural unbalances exacerbated by the euro. Be this as it may, one can, of course, blame the flawed institutional set up and the lack an ultimate action by the ECB as the culprit of the crisis, as Lavoie seems to argue. Yet, since this institutional set up is not there, the EZ crisis manifests itself as a balance of payment crisis.

Excerpt from the conclusion:

… To conclude, since the EZ is closer to a fixed exchange rate regime rather than to a viable, U.S.-style CU, the euro-crisis is akin to a classical BoP crisis. True, the existence of T2 and the possibility of some ECB backing to troubled local sovereign debts make some difference. However, the limits to an ultimate action by the ECB in connection to the absence of other institutions that compose a viable CU render its action necessarily restricted. One can, of course, blame the lack of these institutions and of an ultimate action by the ECB as the culprit of the crisis, as Lavoie and De Grauwe seem to maintain. Yet, since those institutions are not there, the EZ crisis manifests itself as a balance of payment crisis …

Finally, remember the balance-of-payments constraint manifests itself as lower domestic demand and output as much as financial crises.

In general — in other institutional setups, the importance of the government’s power to make drafts at its central bank is exaggerated. It is highly important of course, but problems of balance-of-payments restrain the power of governments in having a fiscal policy independent of what is happening in international trade. In the Euro Area, the lack of critique of the “Common Market” is striking. One can however see these discussions in the works of Nicholas Kaldor.

Unlimited TARGET2 power?

An important point in the current discussion is around the issue of limits of TARGET2. It is true that the TARGET2 system has large powers to absorb imbalances. The intra-Eurosystem debts need not be collateralized. However, when there is capital flight from a nation, banks become more indebted to their NCB. This process can go on for a long time but ultimately it is restricted by collateral banks can provide to their NCB for replenishing lost settlement balances. There is of course the ELA, Emergency Loan Assistance, but this too is limited beyond a point. There is a lot of politics involved here with some nations complaining unfairly on debtor nations’ use of the ELA, but beyond a certain point, their complaints may be fair.

To summarize, TARGET2 is a big shock absorber: beyond what any economist may have expected, but it cannot absorb shocks beyond a limit.

John McCombie Reviews Marc Lavoie’s Post-Keynesian Economics: New Foundations

John McCombie is one of my favourite economists. He is the co-author of the book Economic Growth And The Balance-Of-Payments Constraint, one of the most supremely insightful books.

McCombie has written a review of Marc Lavoie’s book Post-Keynesian Economics: New Foundations, which is the second edition of his book titled Foundations of Post-Keynesian Economic Analysis.

He says:

… the greatest significance of this work is that it clearly demonstrates that there is a coherent and interrelated body of economic theory that stands in marked contrast to the neoclassical framework. Indeed, with the deficiencies of the prevailing orthodoxy exposed by the subprime crisis the publication of this book could not have come at a more propitious time. Some post-Keynesians have concentrated on attacking the foundations of the neoclassical paradigm … to such an extent that it could (and has been) unfairly accused of nihilism.

But as Kuhn has pointed out, a paradigm can only be overthrown by the development of a new paradigm and Marc‘s book shows that there is a substantial corpus of Post Keynesian that meets this criterion. Criticisms of a paradigm is not enough to cause a change in the world view of the practioners …

… It is worth re-emphasizing that one of the great successes of this book is that it takes many important contributions of the Post Keynesians which may otherwise have been lost buried in the journals and integrates them into a coherent story; in a very real sense the sum of this work is greater than the parts.

Read the full review here.

ROKE Issue On Steve Keen’s Notion Of Aggregate Demand

The new issue of ROKE (Review of Keynesian Economics) is online with a few articles available free for some time. Marc Lavoie, Thomas Palley and Brett Fiebiger comment on Keen’s notion of aggregate demand.

Marc Lavoie’s article A comment on ‘Endogenous money and effective demand’: a revolution or a step backwards? is available here.

Steve Keen’s own paper Endogenous money and effective demand is available here.

From Marc Lavoie’s introduction and the ending:

Steve Keen argues that post-Keynesians have not sufficiently emphasized the revolutionary character of endogenous money for macroeconomic theory, and that this should be done by recognizing that aggregate demand is equal to current or past income plus the change in debt. This equation, attributed in particular to Hyman Minsky, is discussed and questioned, and it is recalled that a similar equation had been proposed by Alfred Eichner. The consequences of bank credit for firms or households are further analysed within the context of the national accounts, and it is shown that one does not need a redefinition of aggregate demand and aggregate supply, in contrast to what is proposed by Keen…

…

All post-Keynesians certainly concur with the idea that banks have the capacity to alter the level of aggregate demand, and hence that it would be desirable for banks, debt, and money to be included in models of macroeconomics… There are several examples of post-Keynesian macroeconomic models that incorporate banks, debt, and money – for instance, Godley and Cripps (1983) and Godley and Lavoie (2007), just to mention those that I am most familiar with… But this does not imply, as Keen claims, that we need a redefinition of aggregate demand such that the starting point of macroeconomics is that ‘effective demand is equal to income plus the turnover of new debt’ (Keen 2014a, p. 286). Nor does it mean that aggregate supply needs to be redefined ‘to incorporate the financial markets’ (ibid., p. 290). To provide new definitions of existing terms will only lead to a maze of confusions.

Keen makes the grandiose claim that his approach leads to a ‘new, monetary macroeconomics’ (Keen 2014a, p. 286). While statements of this kind may appeal to an internet audience, I doubt they will convince readers of this journal.

Marc also quotes my blog post Income ≠ Expenditure? which critiqued Keen. (Thanks!).

Tom Palley and Brett Fiebiger’s papers are not available for download by the journal. I will update the post in case ROKE decides to make it available. The permanent links are available in the left column of the papers linked in the post. Palley’s draft version is available here

Also don’t miss the paper by Anthony Thirlwall in the current issue.

Marc Lavoie’s New Book

Marc Lavoie is out with his new book Post-Keynesian Economics: New Foundations. (Publisher’s site for the book)

The book is a considerably extended and fully revamped edition of the highly successful and frequently cited Foundations of Post-Keynesian Economic Analysis, published in 1992. It provides an exhaustive account of post-Keynesian economics and of the developments that have occurred in post-Keynesian theory and in the world economy over the last twenty years. Topics covered include open-economy issues, the methodological foundations of heterodox economics, consumer theory, firms and pricing, money and credit, effective demand and employment, inflation theory, and growth theories.

Chapter 1 is available for download at the publisher’s website here

The Phrase Money Multiplier Itself Is Inaccurate And Misleading

Some people point out that the critique “there is no money multiplier” is wrong because it is a ratio whatever said. No! The phrase “money multiplier” itself is wrong because the phrase itself captures a wrong causal story. A phrase is a small group of words standing together as a conceptual unit and hence the phrase “money multiplier” is inaccurate and misleading.

So take the textbook Keynesian multiplier first. It suggests that a rise in government expenditure leads to a rise in output more than the increase in the expenditure. The ratio of rise in output to the rise in expenditure is the multiplier.

But this is not the case with the “money multiplier”. There is no direction of causality from a rise in bank settlement balances to the rise in the money stock. This is true even if the central bank is doing QE/LSAP, i.e., purchasing assets on a large scale. So if the central bank purchases government bonds in the open market, it leads to a rise in banks’ settlement balances at the central bank and also a rise in the money stock. But the rise in the settlement balances could not have been said to have caused the rise in broad monetary aggregates such as M1, M2 etc. It is the act of the central bank purchase which leads to a rise in the stock of both narrow and broad monetary aggregates.

Now to the case of no QE.

Same story: the rise in banks’ settlement balances could not have been said to have caused a rise in broad monetary aggregates. The more appropriate phrase is “credit divisor”. Here’s Marc Lavoie from his 1984 paper The Endogenous Flow Of Credit And The Post Keynesian Theory Of Money

The Credit “Divisor”

To sum up the monetarist point of view, which, for causality purposes, is similar to the view endorsed by the great majority of economists, one can use equation (2):

M = m B (2)

where m is the monetary multiplier, and where causality is read from right to left, B being the independent variable while M is the dependent one.

On the other hand, the post Keynesian view can be summarized by equation (3):

B = (1/m) M (3)

where 1/m is the so-called credit divisor; B is the dependent variable and M is the independent variable. As a matter of fact, this equation cannot be found explicitly in any of the post Keynesian writings, but it is clear that such a relationship is implied by a large segment of the post Keynesian literature.

The choice between the multiplier and the divisor is a function of the opinions one has about general equilibrium. If one believes that money appears as the result of production processes, that is, as a consequence of the flow of credit created for entrepreneurs by commercial banks, then the multiplier is unacceptable since money becomes a sort of residue, which is incompatible with general equilibrium theorizing. Furthermore, central banks are generally engaged in “defensive” operations, that is, they act according to equation (3).

Another paper of Marc Lavoie informs us that the phrase credit divisor was first used by Louis Levy-Garboua and Vivien Levy-Garboua in a paper in 1972.

Nicholas Kaldor On Rational Expectations

I was recently re-reading an article by Nicholas Kaldor and J. Trevithick [1] and I came across this fine description of rational expectations:

The main plank of the monetarist school has hitherto been that inflation is invariably ‘demand induced’: it can result only from an excessive demand for goods which, however, can manifest itself in the prevalence of excess demand in the labour market [footnote i]. In either case, any consequential increase in output or any fall in unemployment below its natural rate can occur only temporarily.

This latter view, which was shared until recently by the great majority of monetarist economists, is now contradicted by a more radical group of monetarists who developed the notion of ‘rational expectations’ and applied it to the study of inflationary processes. Their position is an extension of the argument that the increase in employment induced by monetary and fiscal policy is the result of some form of ‘cheating’ since workers had expected higher real wages than they actually received, whereas employers had expected to pay a lower real wage than they ultimately had to pay.

It is now claimed by this group of American monetarists that the above theory assumes that expectations are formed on an irrational basis, whereas it is in the interests of all economic agents to form a ‘correct model’ of how the economy functions. The proper cognition of the economy enables rational expectations to be formed which will prevent all but ‘surprise’ departures from an equilibrium path and will, therefore, render nugatory any attempt to reduce unemployment below its ‘natural’ level even in the short run. The centrepiece of this argument is that both workers and employers realise that the quantity theory of money is correct and that wages and prices must rise in the same proportion as the money supply. As a result, it is argued that increased expenditure will cause increases in wages and prices directly without affecting real variables such as output, employment or the real wage rate. They contend that they will base their expectations not on a projection of past trends in the price level or one of its time derivatives (such a procedure would usually be ‘irrational’) but on the ‘correct’ understanding of the economy which takes changing trends into account. Although the mechanism through which prices and wages rise is unclear, this school by-passes the traditional mechanism by which they rise under the pull of excess demand only. The corollary of this hypothesis is that inflation can be reduced far more painlessly than was thought by early monetarists, for, provided that the government can convince the public that it has a firm intention to get the money supply under control, the price level and the level of money wages will respond with only a very short lag: it does not require appreciable restriction of demand in real terms or any abnormal fall in employment even for a temporary period. [footnote ii]

This rational expectations theory goes beyond the untestable basic axioms of the theory of value, such as the utility-maximising rational man whose existence can be confirmed only by individual introspection. The assumption of rational expectations which presupposes the correct understanding of the workings of the economy by all economic agents—the trade unionists, the ordinary employer, or even the ordinary housewife—to a degree which is beyond the grasp of professional economists is not science, nor even moral philosophy, but at best a branch of metaphysics.

[emphasis added]

[footnote i: Harry G. Johnson, ‘What is Right with Monetarism’, Lloyds Bank Review, April 1976]

[footnote ii: It is well known that in the last five years, many Western countries have experienced the phenomenon of rising unemployment coupled with accelerating inflation. This appears to undermine the validity of the traditional natural rate hypothesis and, a fortiori, the rational expectations version. Professor Friedman (‘Inflation and Unemployment’, Institute of Economic Affairs, 1977), has acknowledged this divergence between monetarist theory and empirical observation, but he is hard-pressed to explain it.]

In this recent video, Marc Lavoie (at 28:00) quotes Philip Mirowski saying the same thing:

… orthodox macroeconomists came to conflate ‘being rational’ with thinking like an orthodox economist. What this implied was that agents knew the one and only ‘true model’ of the economy (which conveniently was stipulated as identical with neoclassical microeconomics) …

[1] Kaldor N. and Trevithick J. 1981. A Keynesian Perspective On Money, Lloyd’s Bank Review. (reprinted in Collected Economic Essays, Vol. 9)

Tobinesque Models

Paul Krugman writes today on his blog on James Tobin’s work:

Let me offer an example of how this ended up impoverishing macroeconomic analysis: the strange disappearance of James Tobin. In the 1960s Tobin developed and elaborated a sophisticated view(pdf) [original link corrected] of financial markets that offered insights into things like the role of intermediaries, the effects of endogenous inside money, and more. I’ve found myself using Tobinesque analysis a lot since the financial crisis hit, because it offers a sophisticated way to think about the role of finance in economic fluctuations.

But Tobin, as far as I can tell, disappeared from graduate macro over the course of the 80s, because his models, while loosely grounded in some notion of rational behavior, weren’t explicitly and rigorously derived from microfoundations. And for good reason, by the way: it’s pretty hard to derive portfolio preferences rigorously in that sense. But even so, Tobin-type models conveyed important insights — which were effectively lost.

Compare that to his article in response to another article on Wynne Godley which appeared in the New York Times – completely dismissing Godley’s work.

Three things: first Krugman claimed earlier that we needn’t look at old ideas:

But it is kind of funny to see a revival of old-fashioned macro hailed, at least by some, as the key to a reconstruction of the field

directly contradicting what he says today.

Second – obviously not having read Wynne Godley, he missed the point that Wynne’s analysis has significant improvement of James Tobin’s work.

Third, of course, Krugman’s understanding of monetary economics in general is poor, as can be seen when he gets into debates with heteredox economists and makes the most elementary errors. So it is strange he is lecturing others on this and fails once again to acknowledge heteredox economists.

Here’s Marc Lavoie describing in his article From Macroeconomics to Monetary Economics: Some Persistent Themes in the Theory Work of Wynne Godley in the book Contributions to Stock-Flow Modeling: Essays in Honor of Wynne Godley:

As Godley points out on a number of occasions, he himself owed his formalization of portfolio choice and of the fully consistent transactions-flow matrices to James Tobin. Godley was most particularly influenced and stimulated by his reading of the paper by Backus et al. (1980), as he writes in Godley (1996, p. 5) and as he told me verbally several times. The discovery of the Backus et al. paper, with its large flow-of-funds matrix, was a revelation to Godley and allowed him to move forward. But as pointed out in Godley and Lavoie (2007, p. 493), despite their important similarities, there is a crucial difference in the works of Tobin and Godley devoted to the integration of the real and monetary sides. In Tobin, the focus is on one-period models, or on the adjustments from the initial towards the desired portfolio composition, for a given income level. As Randall Wray (1992, p. 84) points out, in Tobin’s approach ‘flow variables are exogenously determined, so that the models focus solely on portfolio decisions’. By contrast, in Godley and Cripps and in further works, Godley is preoccupied in describing a fully explicit traverse that has all the main stock and flow variables as endogenous variables. As he himself says, ‘the present paper claims to have made … a rigorous synthesis of the theory of credit and money creation with that of income determination in the (Cambridge) Keynesian tradition’ (Godley, 1997, p. 48). Tobin never quite succeeds in doing so, thus not truly introducing (historical) time in his analysis, in contrast to the objective of the Godley and Cripps book, as already mentioned earlier. Indeed, when he heard that Tobin had produced a new book (Tobin and Golub, 1998), Godley was quite anxious for a while as he feared that Tobin would have improved upon his approach, but these fears were alleviated when he read the book and realized that there was no traverse analysis there either.

Draft link here.