The recent debates of Post Keynesians with Neoclassical/New Keynesians has highlighted that the latter group continues to hold Monetarists’ intuitions. Somehow the exogeneity of money is difficult for them to get rid of, in spite of their statements and rhetoric that money is endogenous in their models.

So there is an excess of money in their models and this gets resolved by a series of buy and sell activities in the “market” (mixing up decisions of consumption and portfolio allocation) until a new “equilibrium” is reached where there is no excess money.

Two-Stage Decision

While the following may sound obvious, it is not to most economists. Keynes talked of a two-stage decision – how much households save out of their income and how they decide to allocate their wealth. In the incorrect “hot potato” model of Neoclassical economists and their New “Keynesian” cousins, these decisions get mixed up without any respect for the two-stage decision. It is as if there enters an excess money in the economy from somewhere and people may consume more (as if consumption is dependent on the amount of deposits and not on income) till prices rise to bring the demand for money equal to what has been “supplied” (presumably by the central bank).

In their book Monetary Economics, Wynne Godley and Marc Lavoie have this to say (p 103):

A key behavioural assumption made here, as well as in the chapters to follow, is that households make a twostage decision (Keynes 1936: 166). In the first step, households decide how much they will save out of their income. In the second step, households decide how they will allocate their wealth, including their newly acquired wealth. The two decisions are made within the same time frame in the model. However, the two decisions are distinct and of a hierarchical form. The consumption decision determines the size of the (expected) end-of-period stock of wealth; the portfolio decision determines the allocation of the (expected) stock of wealth. This behavioural hypothesis makes it easier to understand the sequential pattern of household decisions.

[Footnote]: In his simulation work, but not in his theoretical work, Tobin endorsed the sequential decision that has been proposed here: ‘In the current version of the model households have been depicted as first allocating income between consumption and savings and then making an independent allocation of the saving among the several assets’ (Backus et al. 1980: 273). Skott (1989: 57) is a concrete example where such a sequential process is not followed in a model that incorporates a Keynesian multiplier and portfolio choice.

Constant Money?

So even if one agrees that loans make deposits, there is still a question of deposits just being moved around and the (incorrect) intuition is that someone somewhere must be holding the deposit and hence similar to the hot potato effect. The error in this reasoning is the ignorance that repayment of loans extinguishes money (meant to be deposits in this context).

Nicholas Kaldor realized this Monetarist error early and had this to say

Given the fact that the demand for money represents a stable function of incomes (or expenditures), Friedman and his associates conclude that any increase in the supply of money, however brought about (for example, through open-market operations that lead to the substitution of cash for short-term government debt in the hands of discount houses or other financial institutions), will imply that the supply of money will exceed the demand at the prevailing level of incomes (people will “find themselves” with more money than they wish to hold). This defect, in their view, will be remedied, and can only be remedied, by an increase in expenditures that will raise incomes sufficiently to eliminate the excess of supply over the demand for money.

As a description of what happens in a modern economy, and as a piece of reasoning applied to situations where money consists of “credit money” brought about by the creation of public or private debt, this is a fallacious piece of reasoning. It is an illegitimate application of the original propositions of the quantity theory of money, which (by the theory’s originators at any rate) were applied to situations in which money consisted of commodities, such as gold or silver, where the total quantity in existence could be regarded as exogenously given at any one time as a heritage of the past; and where sudden and unexpected increases in supply could occur (such as those following the Spanish conquest of Mexico), the absorption of which necessitated a fall in the value of the money commodity relative to other commodities. Until that happened, someone was always holding more gold (or silver) than he desired, and since all the gold (and silver) that is anywhere must be somewhere, the total quantity of precious metals to be held by all money-users was independent of the demand for it. The only way supply could be brought into conformity, and kept in conformity, with demand was through changes in the value of the commodity used as money.

[boldening: mine]

from Nicholas Kaldor wrote a major article in 1985 titled How Monetarism Failed (Challenge, Vol. 28, No. 2, link).

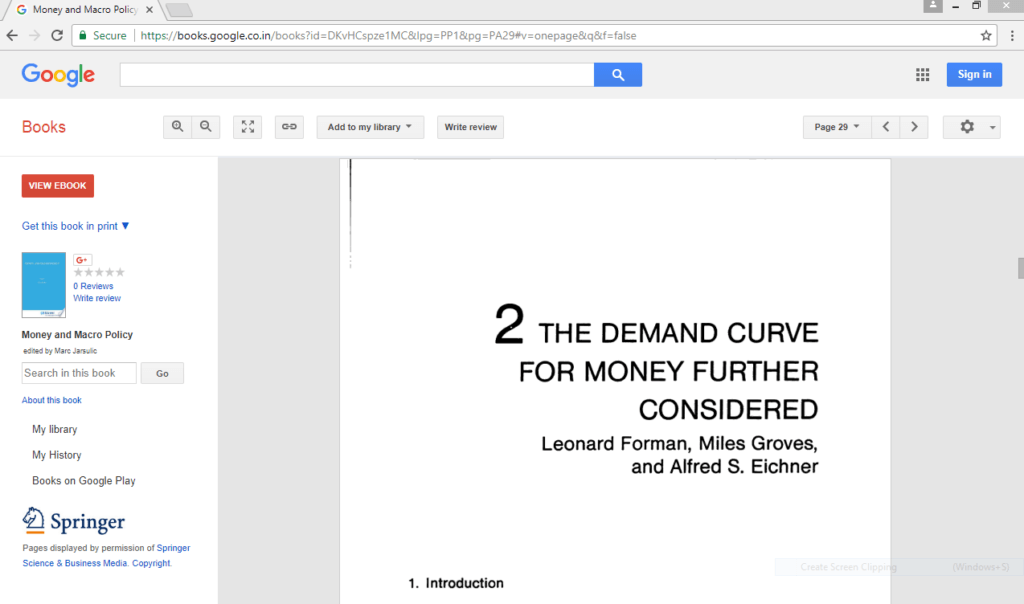

In his essay Keynesian Economics After Fifty Years, (in Keynes And The Modern World, ed. George David Norman Worswick and James Anthony Trevithick, Cambridge University Press, 1983), Kaldor wrote:

The excess supply would automatically be extinguished through the repayment of bank loans, or what comes to the same thing, through the purchase of income yielding financial assets from the banks.

Here’s the Google Books preview of the page:

click to view on Google Books

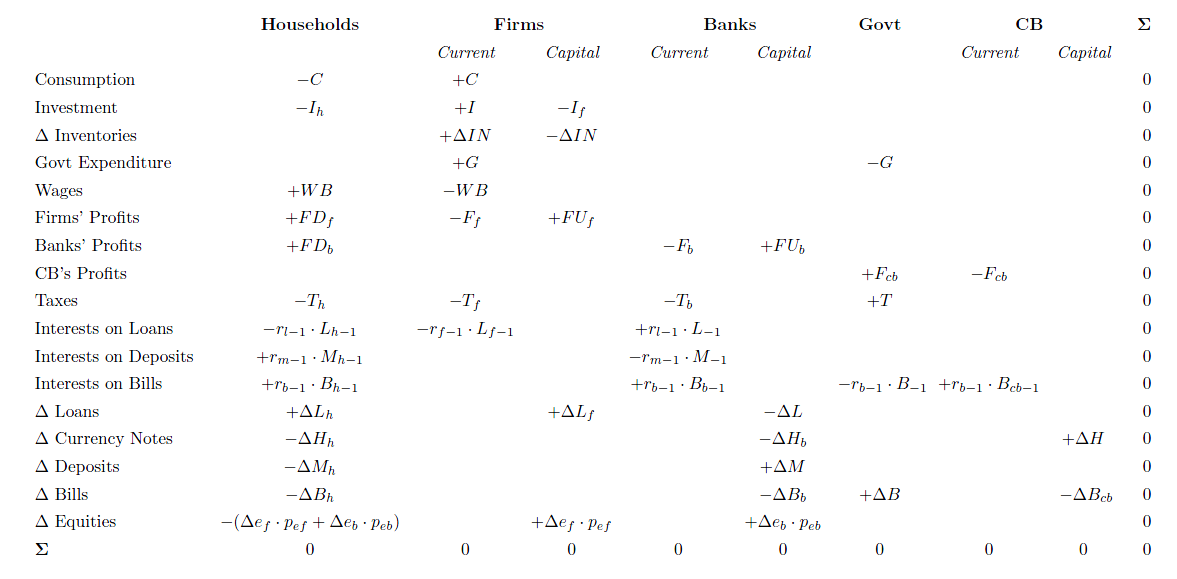

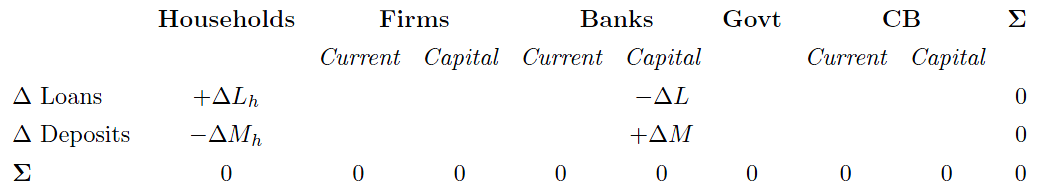

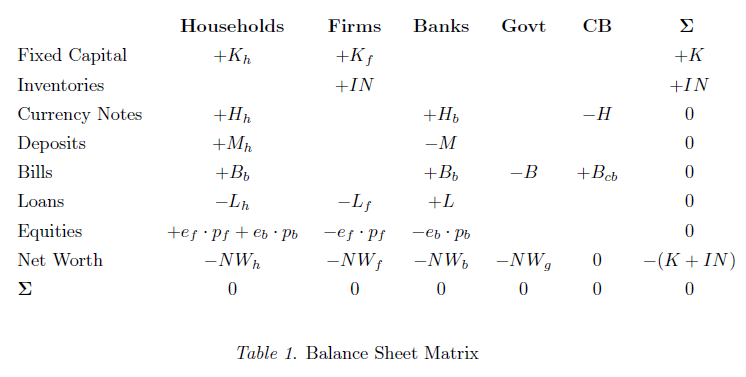

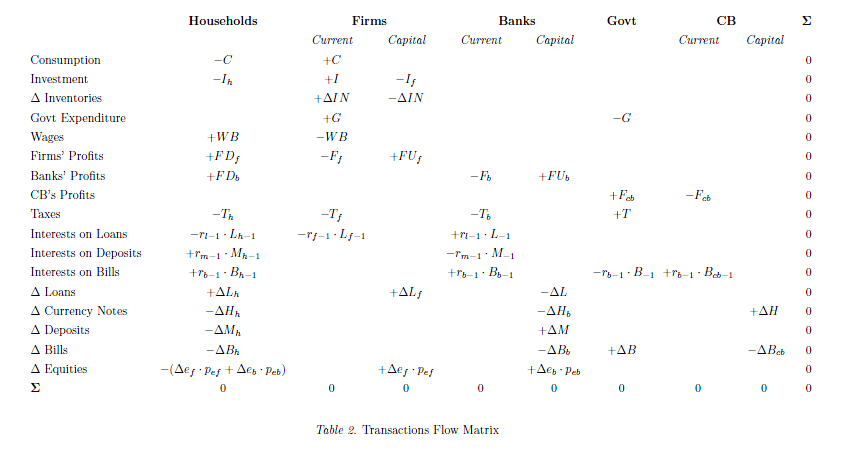

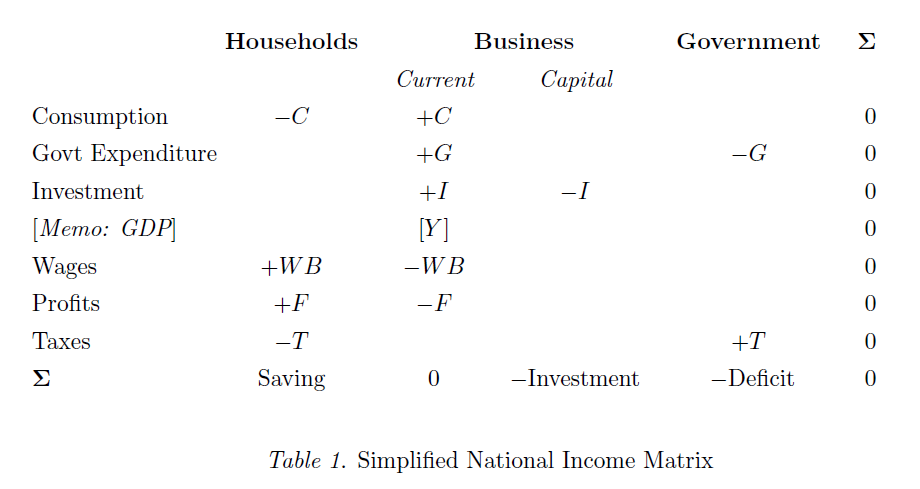

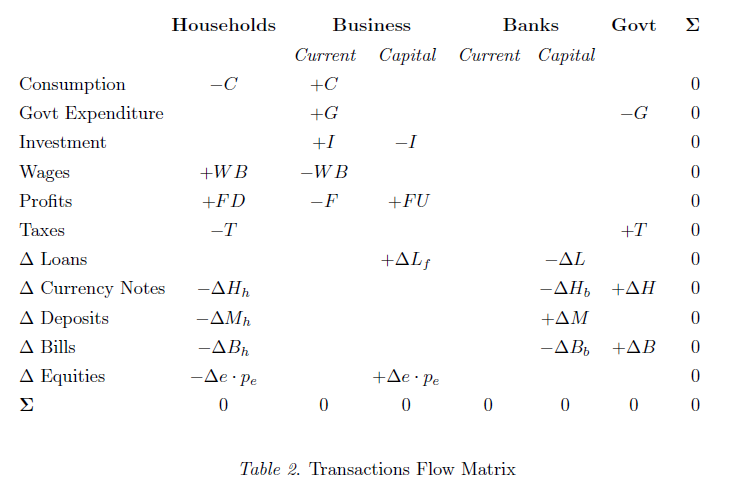

In his article, Circuit And Coherent Stock-Flow Accounting, (in Money, Credit, and the Role of the State: Essays in Honour of Augusto Graziani, 2004. Google Books link) Marc Lavoie showed how this precisely works using Godley’s transactions flow matrix. (Paper available at UMKC’s course site). See Section 9.3.1

The fact that the supply of credit and demand for money appeared to be independent

… has led some authors to claim that there could be a discrepancy between the amount or loans supplied by banks to firms and the amount or bank deposits demanded by households. This view of the money creation process is however erroneous. It omits the fact that while the credit supply process and the money-holding process are apparently independent, they actually are not, due to the constraints or coherent macroeconomic accounting. In other words, the decision by households to hold on to more or less money balances has an equivalent compensatory impact on the loans that remain outstanding on the production side.

So if households wish to hold more deposits, firms will have to borrow more from banks. If households wish to hold less deposits, they will purchase more equities (in the model) and hence firms will borrow lesser from banks and/or retire their debt toward banks.

Other References

- Lavoie, M. 1999. The Credit-Led Supply Of Deposits And The Demand For Money – Kaldor’s Reflux Mechanism As Previously Endorsed By Joan Robinson, Cambridge Journal Of Economics. (journal link)

- Kaldor N. and Trevithick J. 1981. A Keynesian Perspective On Money, Lloyd’s Bank Review.