Earlier, I had two posts on this but now these have been merged into one.

Chartalists again!

This blog post The fiscal role of the KfW – Part 1 by Bill Mitchell of Australia makes the most exorbitant claims about an institution called KfW and the government of Germany.

Bill Mitchell claims:

It is a major reason why the public debt ratio in Germany is 80 per cent rather than close to 100 per cent. It is a major reason why the federal deficit has been reduced without scorching the German economy. It is a story about smoke-and-mirrors accounting, German-style.

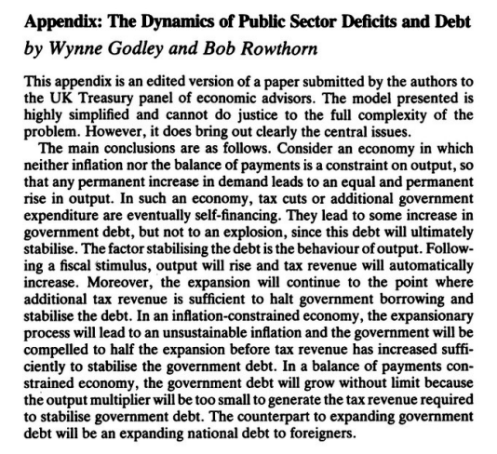

This is a bizarre claim. For Mitchell’s claim on the deficit to be valid, KfW should be a net borrower each year of a big size. For the claim on the public debt, KfW’s net indebtedness should be large. If Mitchell means anything other than this when saying “fiscal role”, what is it?

Unfortunately for Mitchell, KfW is a net lender to the private sector and the rest of the world sector in the flow sense and a net creditor in the stock sense.

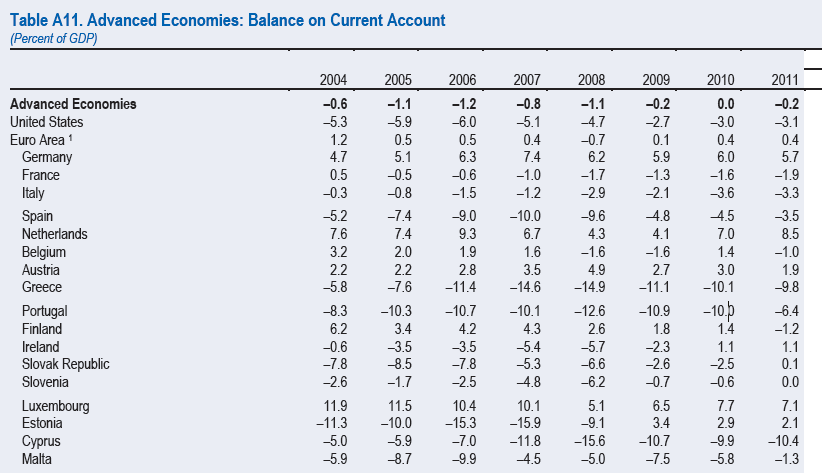

First, Germany’s 2012 GDP was €2.666tn (source: OECD.StatExtracts) and 1% of that is about €26.66bn and 20% of GDP is €533bn.

Here’s the 2012 financial report of KfW.

Let’s get an order of magnitude of the numbers. The net lending of KfW would identically be its undistributed profits minus capital expenditure. KfW doesn’t distribute profits (page 10 of the report) and so its undistributed profits is equal to its profits. Page 66 of the financial report says 2012 profits is €2.38bn and capital expenditure is negligible (page 72).

Hence KfW is a net lender and not a net borrower!

In other words, Prof. Mitchell seems to present a story in which the German government is using KfW as a tool to have a higher budget deficit than what it shows in its own books but it is in fact the opposite. This is because the combined entity KfW + Government of Germany has a lower deficit than the deficit of the government of Germany.

Moving to the balance sheet, its size is about €511bn – also quoted by Mitchell. But the size is not the main thing here. It is whether KfW is a net debtor or not. The balance sheet (page 68) says that equity is about €20.69bn. Of course, the item equity doesn’t by itself say anything about net indebtedness – an economic unit can possibly have a large net worth (in this case with no stock market shares issued, the same as equity) and yet be a net debtor if it holds a large proportion of its assets in non-financial form. The balance sheet however suggests that this is not the case – property, plant and equipment and intangible assets are small compared to other numbers.

Hence KfW is a net creditor and nothing like an institution with net indebtedness of about €533bn (100% minus 80% of GDP, see the quote at the start of this post.)

This was for 2012 but for other years just mirror the analysis – different numbers but of order of magnitude like these and nothing like what Prof. Mitchell interprets them to be. Supposedly, according to him, KfW

It spends, I mean lends millions each year at very low rates … pumps millions of Euros in the domestic economy and the export sector.

I suppose it subsidies lending and the fiscal part is how these subsidies are calculated and not the amount of lending which Mitchell seems to present by saying “pumps millions of Euros”. These lending flows are not like a government expenditure flow.

And spending is not lending!

In other words, the subsidy provided indirectly by the government via KfW. This can perhaps be estimated by the profits of a domestic bank of similar size or by some similar sort of comparison – and estimating what profits would have been otherwise. After this one would compare it to various numbers in the government budget. This however in my opinion will be nothing like what Mitchell makes it out to be.

Further Bill Mitchell makes another claim:

There are three reasons to look closely at the KfW:

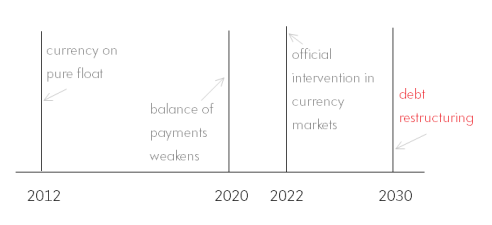

1. It played a role in the Deutsche Telekom (so-called) privatisation, which helped the German government slip out of an embarassing excessive deficit procedure in 2004. Sleight-of-hand is the best description for what happened.

…

Except that there was no sleight-of-hand.

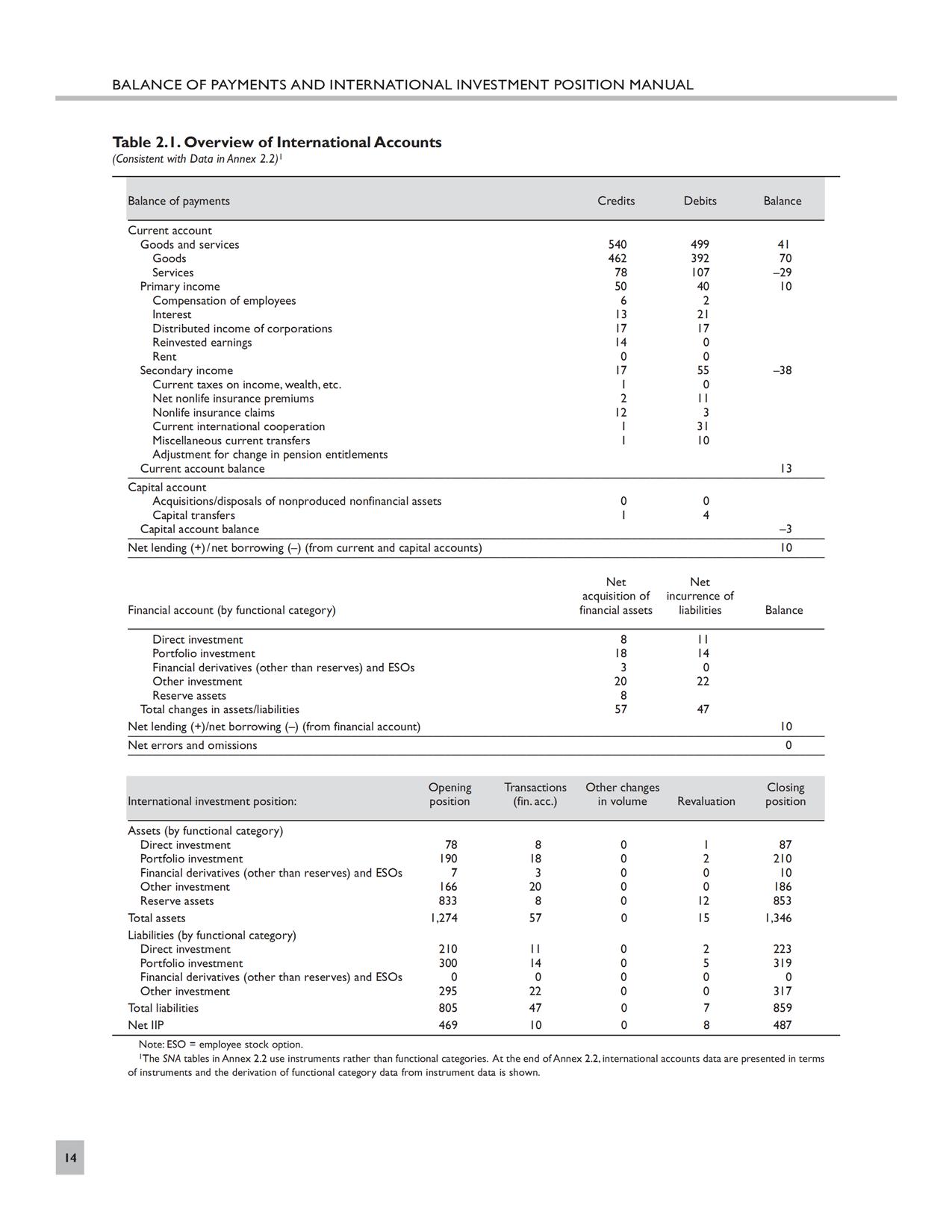

In national accounts such as in the 2008 SNA, items such as privatization appear in the financial account and perhaps sometimes in the “other changes in assets accounts”. This ECB Convergence Report June 2013, page 68, box 6 says:

a reduction in financial assets (as a result of privatisations for instance) tends to reduce the borrowing requirement as it generates cash, while leaving the deficit unchanged.

In other words, the privatization of Deutsche Telekom has no effect on the deficit. It reduces the public sector borrowing requirement and the public debt, but the private sector net worth doesn’t change at the time of the transaction. So it is not as if the private sector holds more of financial assets as a result of the privatization. It may see holding gains but that is a different matter.

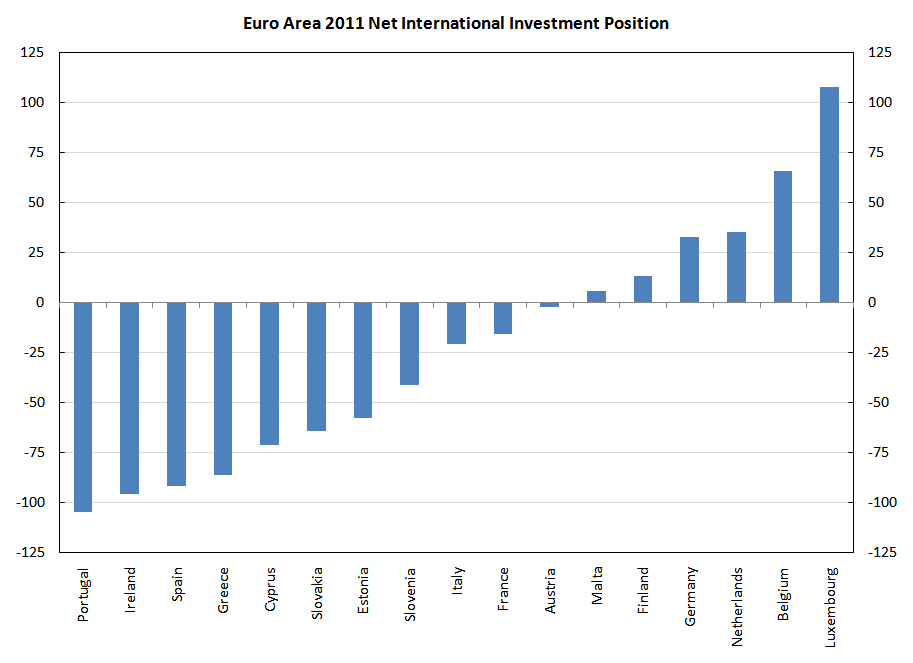

At any rate, what would have been the alternative to bring the gross public debt down to meet the debt-deficit-criteria? Attempt to deflate German domestic demand and consequently demand and output in the rest of the Euro Area?

Also, even if one counts the effect of privatization in the deficit, it would have Germany’s deficit from 4.3% to 4.2%. As a commentator in Billy Blog writes:

Take for instance the purchase in November 2003, which according to you was done as a result of the pressure from the EU in reducing the deficit. The KfW purchased about 200 Million stocks, wow, sounds impressive… except the actual value of those stocks was only about 2.5 Billion €. The german deficit in 2003 was 89 Billion € or 4.2% of the GDP, so without the KwF buy it would have been… 4.3% (if you round up generously). The KfW buys and sells had no practical relevance for Germany either going below or above the deficit rule of the Growth and Stability Pact – the sums involved were simply not big enough for that.

Thus, the entire story about the supposed fiscal role of the KfW is incorrect.

More Strange Claims On KfW (10 Dec 2013)

Phil Pilkington writes in defense of Bill Mitchell in response to my previous post Strange Claims About KfW [Updated].

Pilkington’s errors are simple accounting errors and misunderstanding of flow-of-funds. Pilkington seems to assume the same logic of Mitchell. According to him:

The trick is that this borrowing doesn’t appear on the government balance sheet so, given a level of aggregate net expenditure equal to,

[Government Deficit + KfW Lending],

the Federal deficit is lower than it would otherwise be if the government had to foot the bill for all this expenditure.

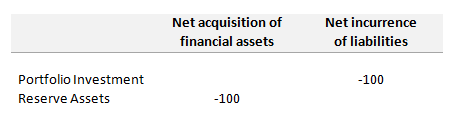

First, the government would not have to “foot the bill for this expenditure” if it were to lend directly to the private sector on its books because the lending would not be “expenditure” but a loan by the government and it would be making a profit on it. The loan would not add to the budget balance even if the government were to directly lend. The expenditure would be for the firm using the proceeds of the loan and it is not public expenditure. Pilkington seems to confuse income/expenditure flows with financial flows. Or in the language of the 1993/2008 SNA confuses current accounts with the financial account.

In fact the profits if the government were to lend directly would reduce the federal deficit by a bit, not increase as claimed by Pilkington.

Further Pilkington seems to assume that another counter-factual in this case is less borrowing by the private sector and hence lesser private expenditure. No! this counter factual is the private sector borrowing from other banks – i.e, private banks. Why would German firms find difficulty in borrowing if they happened to show their creditworthiness to KfW?

Also, as I highlighted in the previous post, a proxy for the subsidy would be the profit of the bank of a similar size minus the actual profit of KfW. It is nothing like Mitchell’s rabble-rouse.