Dani Rodrik has a Project Syndicate article titled No More Growth Miracles and in my view rightly identifies problems of the world economy, although has less to say how to resolve the crisis.

These were most well understood by Nicholas Kaldor (who was touched by genius in Wynne Godley’s words). In the previous post How To Find Nicholas Kaldor’s Works, I recommended his Rafaelle Matiolli Lectures which appeared in a book form titled Causes Of Growth And Stagnation In The World Economy.

The lectures were given in May 1984.

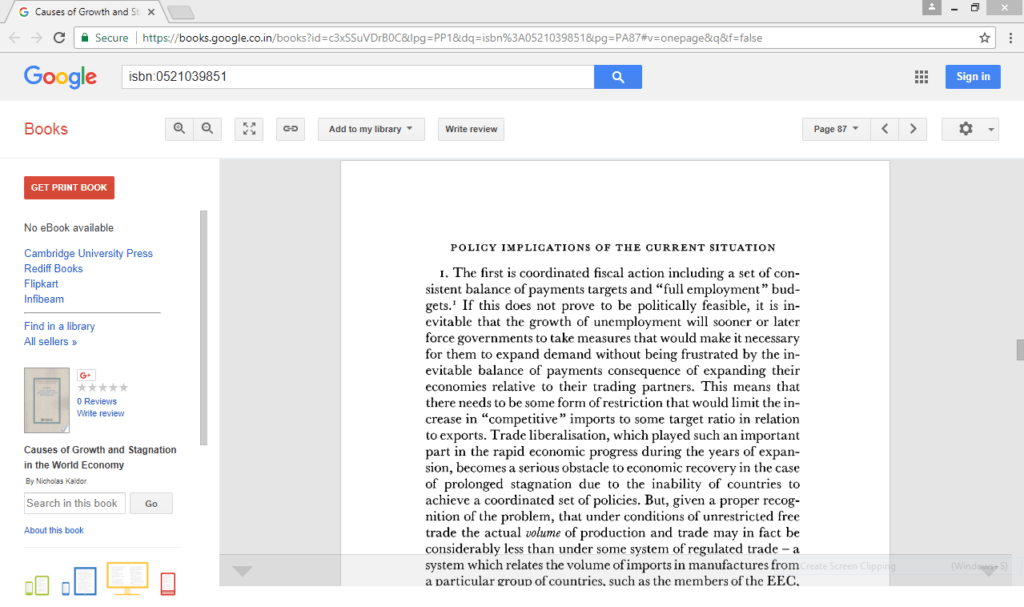

In the fifth and final lecture Kaldor – who understood the shortcomings of Keynesian economics – after having lectured on the causes of growth and stagnation in the world economy, summarizes the situation (page 86):

The fact that OPEC (as a group) is now in deficit on its current balance, and that Britain’s current account surpluses have virtually disappeared while the United States is in a large deficit, makes it a great deal easier for other developed countries to expand their economies than at any time since 1973. But there is still need for coordinated action, at least among the members of the European Community. As the French example has shown, an expansionary budget which is out of line with the fiscal stance of the other main countries of the group, quickly gets a country into serious payments difficulties owing to the resulting imbalance in trade.

But – as is the case now – and even back then policy makers meet and don’t do much ….

The lack of agreement on the fundamental lines of a policy for economic recovery is acutely felt, and the need for it is shown by the increasing frequency of inter-Governmental meetings at various levels: the next world summit meeting in which the heads of the leading western powers all participate is due to take place in London in a few weeks’ time.

If, by some miracle, this summit meeting, unlike all its predecessors, resulted in a constructive programme of recovery, what should its main provisions contain? I should like to end this series of lectures by suggesting the outline of a world-wide agreement on the necessary policies for recovery. The programme could be summed up under four main heads:

In present times, there are very few – in my opinion – who recognizes what needs to be done. Kaldor continues:

1. The first is coordinated fiscal action including a set of consistent balance of payments targets and “full employment” budgets [footnote]. If this does not prove to be politically feasible, it is inevitable that the growth of unemployment will sooner or later force governments to take measures that would make it necessary for them to expand demand without being frustrated by the inevitable balance of payments consequence of expanding their economies relative to their trading partners. This means that there needs to be some form of restriction that would limit the increase in “competitive” imports to some target ratio in relation to exports. Trade liberalisation, which played such an important part in the rapid economic progress during the years of expansion, becomes a serious obstacle to economic recovery in the case of prolonged stagnation due to the inability of countries to achieve a coordinated set of policies. But, given a proper recognition of the problem, that under conditions of unrestricted free trade the actual volume of production and trade may in fact be considerably less than under some system of regulated trade – a system which relates the volume of imports in manufactures from a particular group of countries, such as the members of the EEC, to some mutually agreed ratio to the exports of individual members to the rest of the group – there is no reason why full employment should not be restored through policies of expansion, preferably directed by the expansion of State investment. This coordinated action by all countries, instead of isolated actions by each country, is the first and most important requirement of recovery.

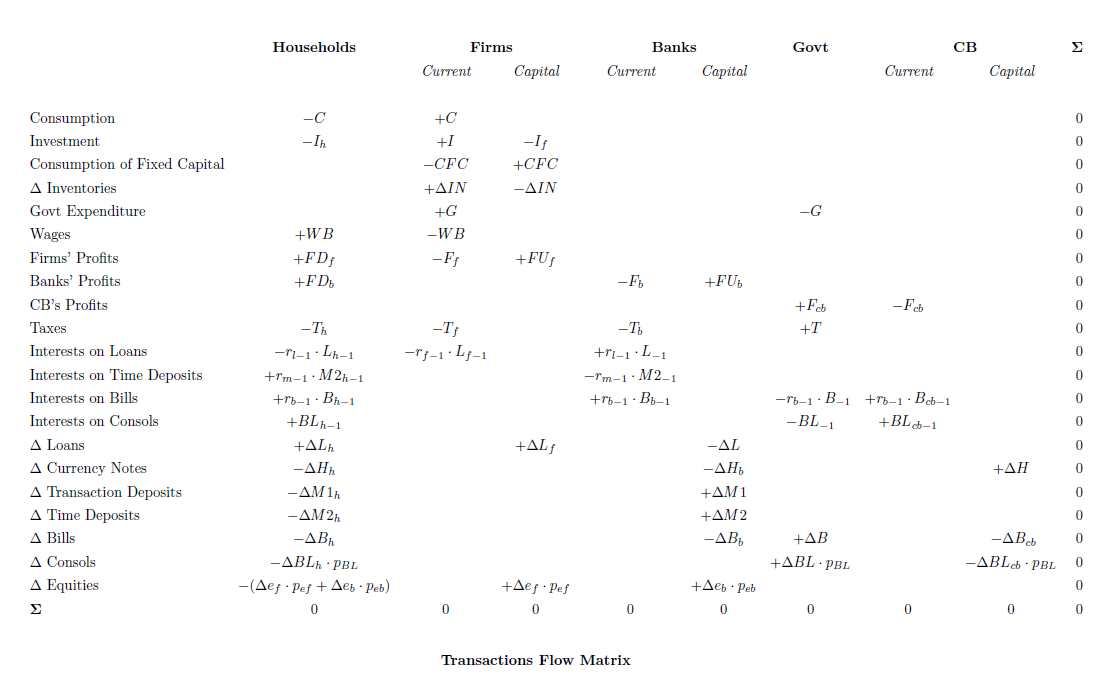

Keynesians and others who have come to understand fiscal policy are however too late. A unilateral fiscal expansion by one country will soon lead to balance of payments problems for it with the result that fiscal policy has to give in and become endogenous sooner or later. (Such is the case with India now, for example). So fiscal expansions need to be coordinated with other countries.

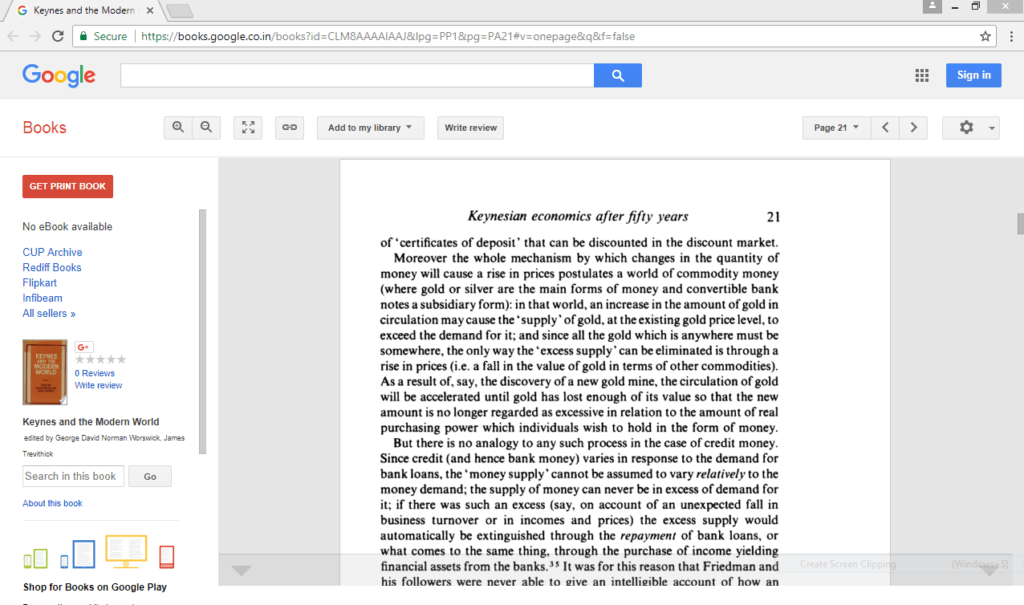

Also there is a footnote suggesting how the endogeneity of the budget deficit is commonly misunderstood:

Footnote: At present all countries have fairly large deficits in the general government budget, but these are largely the consequence of the low level of activity. On a “full employment” basis they would show a highly restrictive picture – they would show surpluses and not deficits. Contrary to appearances, the requirement of stability is for expansionary budgets with lower taxes and higher expenditure, and not further fiscal restriction (as is advocated, for example, by M. de Larosiere of the International Monetary Fund).

Point 2 is about bringing interest rates to as low as possible and this we already have in the present crisis. Point 3 is about stabilization commodity prices and point 4 about the problem of inflation which was more troublesome in the past due to trade unions’ bargaining.

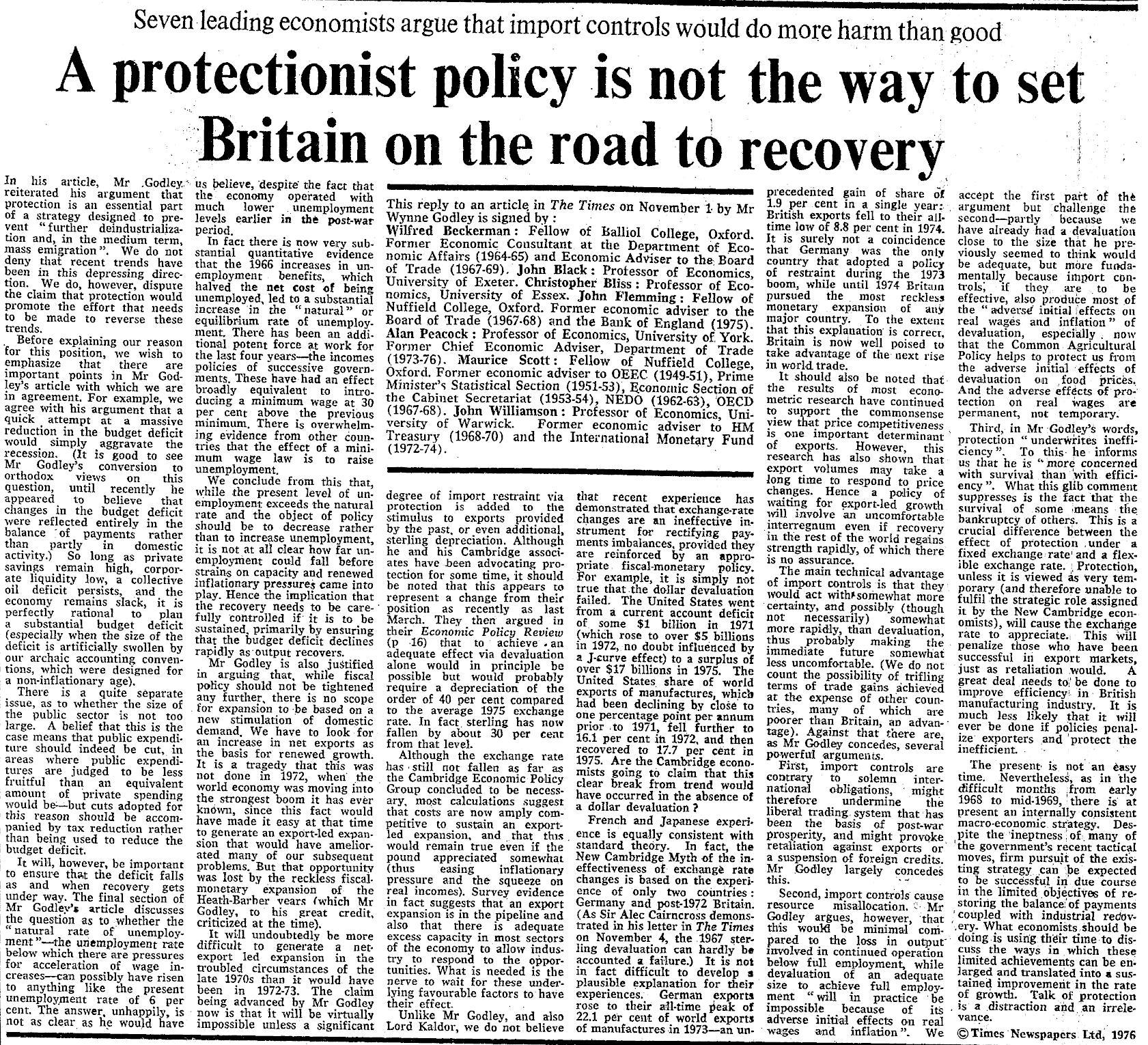

Point 1 is the most important and relevant to the current scenario. Over the years, credit-led growth led to a boom which finally went bust but leaving the world with more “global imbalances”. Economists and politicians wish to resolve the crisis without giving up the doctrine of free trade. At least there is a pressure from the developed world to maintain status quo in spite of resistance from the developing world. As a recent article Protectionism Alert from The Economist recognizes, there is a tendency to move toward more protectionism in practice however which the magazine wishes to alert to the world – so that it is noted and steps taken beforehand to prevent it and free trade is pushed even more.

It should be noted that Kaldor’s plan is more than “coordinated fiscal expansion”. It is also about managing trade instead of relying on market forces. As argued by his “New Cambridge” colleagues, and stated by Kaldor, this will not lead to a decrease in world trade but actually an increase because of higher national output and income!

The first head of the programme is indeed what the world needs at the moment.

One of the listeners of his lectures was Mario Monti! More interestingly, Monti has a question to ask on this plan of Kaldor.

Here’s the Google Books Preview:

click to view on Google Books