The subject of money, credit and moneyflows is a highly technical one, but it is also one that has a wide popular appeal. For centuries it has attracted quacks as well as serious students, and there has too often been difficulty in distinguishing a widely held popular belief from a completely formulated and tested scientific hypothesis.

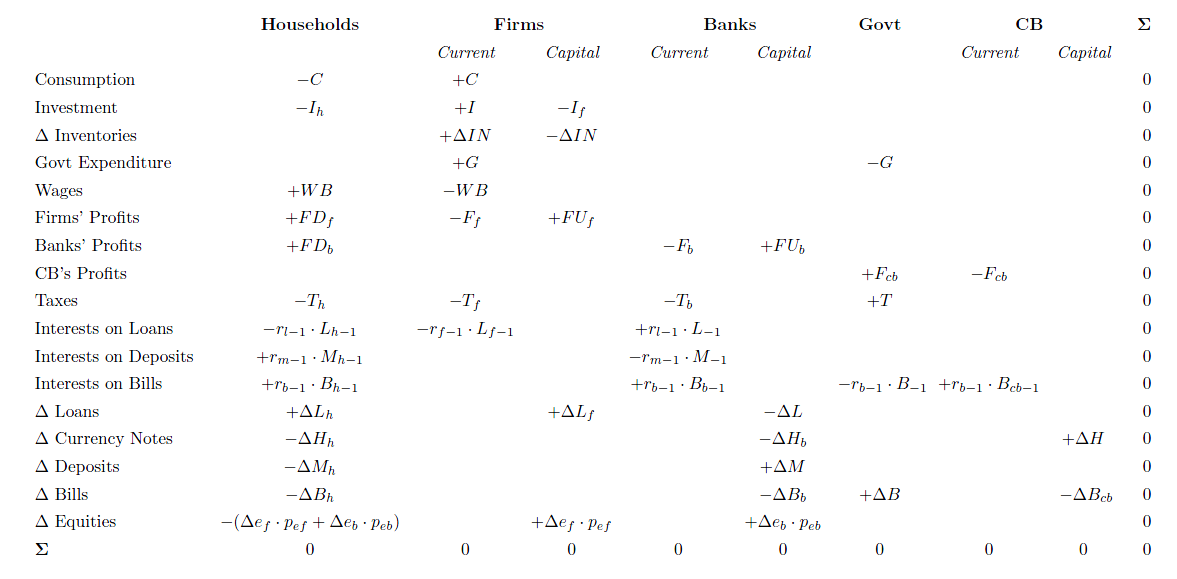

I have said that the subject of money and moneyflows lends itself to a social accounting approach. Let me go one step farther. I am convinced that only with such an approach will economists be able to rid this subject of the quackery and misconceptions that have hitherto been prevalent in it.

– Morris Copeland, inventor of the Flow Of Funds Accounts of the United States, in Social Accounting For Moneyflows, in Flow-of-Funds Analysis: A Handbook for Practitioners (1996) [article originally published in 1949]

So the news is that Eugene Fama shares this year’s Economics Nobel with Robert Shiller and Lars Hansen.

Instead of going into Fama’s main work, I thought I will point out Fama’s quackery on national accounts and flow of funds – which economists are supposed to know but is rarely the case.

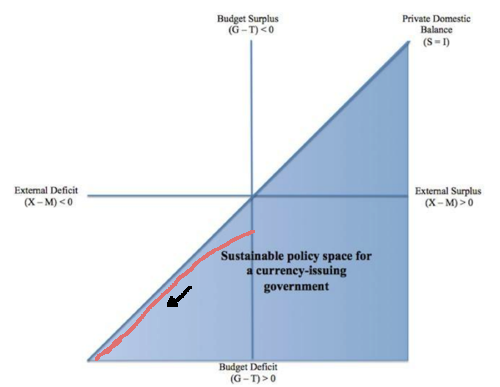

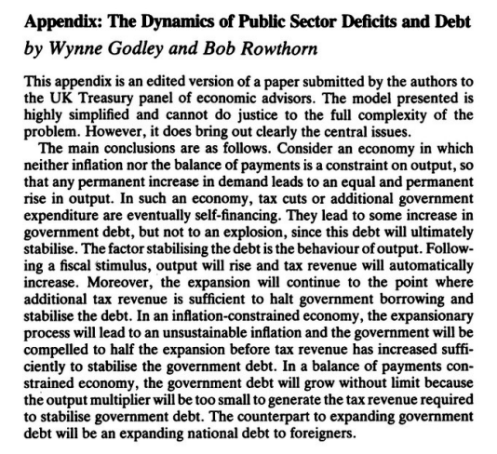

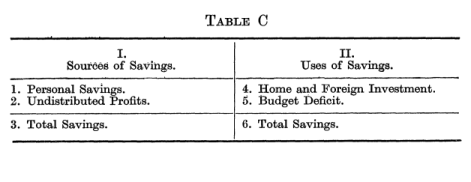

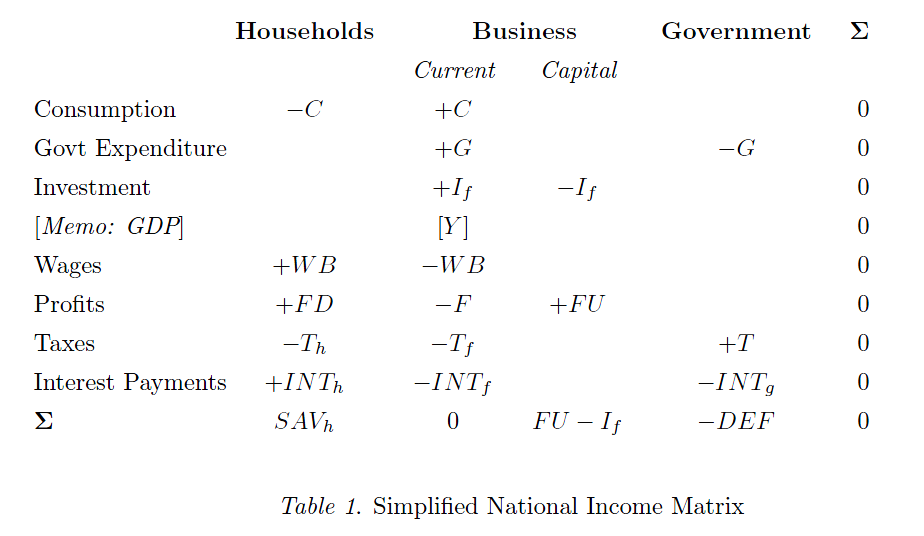

In an article from 2009, Bailouts and Stimulus Plans, Fama again puts down fiscal policy in a rather comical way. Fama starts with the sectoral balances identity:

There is an identity in macroeconomics. It says that in any given year private investment must equal the sum of private savings, corporate savings (retained earnings), and government savings (the government surplus, which is more likely negative, that is, a deficit),

PI = PS + CS + GS (1)

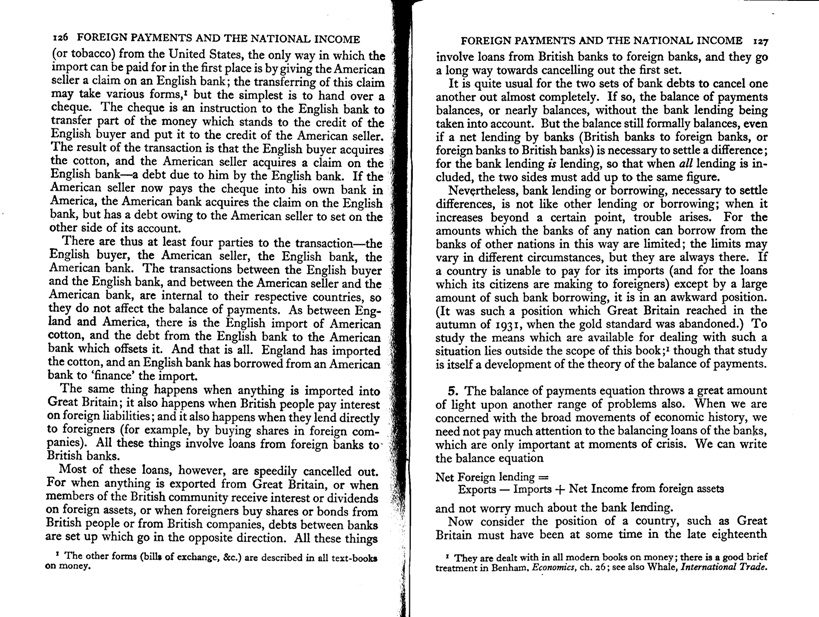

In a global economy the quantities in the equation are global. This means the equation need not hold in a particular country, but it must hold in the world as a whole.

There is so much muddle to start the analysis. The above is incorrect to start with because “private savings” automatically includes corporate savings. Perhaps this error is a typo but going through his analysis doesn’t support the hypothesis that he even knows the equation right. Incidentally government saving is not government surplus in standard terminology. He seems to think these are equal.

Another error in the above equation is that the left hand side should include government investment as well.

Anyway …

Fama continues:

Government bailouts and stimulus plans seem attractive when there are idle resources – unemployment. Unfortunately, bailouts and stimulus plans are not a cure. The problem is simple: bailouts and stimulus plans are funded by issuing more government debt. (The money must come from somewhere!) The added debt absorbs savings that would otherwise go to private investment.

There are so many incorrect things with this. First, there is a reverse causality in the saving/investment identity. Investment creates saving. Second, Fama seems to think that government deficit reduces private saving but the identity itself is suggestive of another interpretation. If I write it as (in the context of a closed economy):

S = I + G – T

where S is the private saving, I is private investment and G and T are government expenditure and tax receipts, respectively. It then becomes clear that government deficit – instead of reducing private saving, creates private saving.

Even more worrisome is his statement “the money must be somewhere” – as if the stock of money is an exogenously fixed quantity. A fiscal expansion (meaning higher governmen expenditure and/or decrease of tax rate) can increase the stock of money in two ways. First is direct – if there is a government deficit with the fiscal expansion and banks purchase a fraction of government debt, the stock of money increases. The second is via a rise in domestic demand which will lead to higher borrowing by the private sector from banks thereby increasing the money stock. Of course there are other effects too via the non-bank private sector asset allocation decisions etc.

Not going in much details for now as I write a lot about it and in any case there is Post-Keynesian monetary economics on this. My aim was to show how an economics Nobel Prize winner is clueless about basic economics! The prize is to be awarded to people who have made great contributions to society but we have an example of someone – Fama – who pushes fiscal contraction with clueless analysis of national accounts.