Thomas Piketty gets dismissed a lot: from the right-wing since they either think there’s much inequality or that it’s unimportant. From the left, he gets ridiculed for not being a Marxist or even Post-Keynesian/Keynesian enough. Whatever the criticisms, there are some things which he says which are useful and highly important in the current political climate. My view is that he is a bit late to it but some of his analysis adds more light.

In his book Capital And Ideology, he talks of how the dynamics of winners against losers of globalisation creates interesting politics. For example in pages 812-817:

Will the Democratic Party Become the Party of the Winners of Globalization?

…

Nevertheless, other factors cast doubt on the long-term viability of a transformation of the Democratic Party into the party of the winners of globalization in all its dimensions: educational as well as patrimonial. First, the presidential debates of 2016 showed the degree to which cultural and ideological differences remain between the Brahmin and merchant elites. Whereas the intellectual elite stressed values of level-headed rationality and cultural openness, which Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton sought to project, business elites favored deal-making ability, cunning, and virility, of which Donald Trump presented himself as the embodiment.16 In other words, the system of multiple elites has not yet breathed its last because at bottom it rests on two different and complementary meritocratic ideologies. Second, the 2016 presidential election showed the risk that any political party runs if it becomes too blatantly identified as the party of the winners of globalization. It then becomes the target of anti-elitist ideologies of all kinds: in the United States in 2016, this allowed Donald Trump to deploy what one might call the nativist merchant ideology against the Democrats. I will come back to this.

Last but not least, I do not believe that this evolution of the Democratic Party is viable in the long run because it does not reflect the egalitarian values of an important part of the Democratic electorate and of the United States as a whole …

- Note that the recourse to overtly anti-intellectual and anti-Brahmin leaders like Donald Trump is not limited to the US Republican Party: the European right has gone in a similar direction as shown by the choice of a Silvio Berlusconi in Italy or a Nicolas Sarkozy in France.

and on the EU referendum/Brexit, page 861, Chapter Sixteen, Social Nativism: The Postcolonial Identitarian Trap:

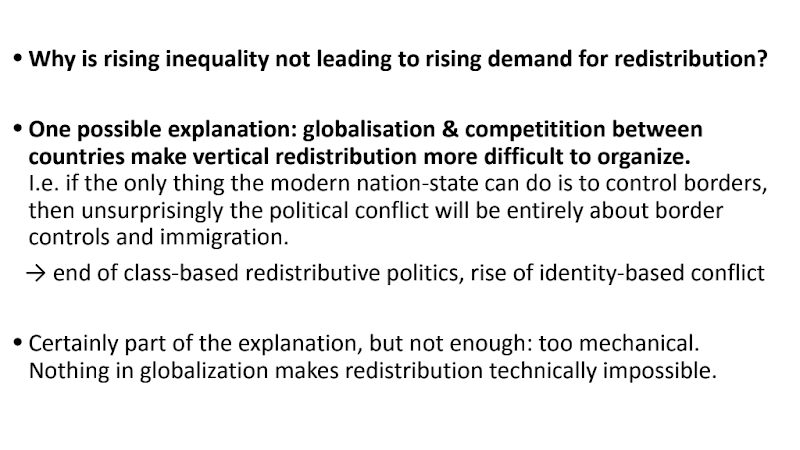

… in all three countries [United Kingdom, United States, and France], the “classist” party systems of the period 1950–1980 gradually gave way in the period 1990–2020 to systems of multiple elites, in which a party of the highly educated (the “Brahmin left”) and a party of the wealthy and highly paid (the “merchant right”) alternated in power. The very end of the period was marked by increasing conflict over the organization of globalization and the European project, pitting the relatively well-off classes, on the whole favorable to continuation of the status quo, against the disadvantaged classes, which are increasingly opposed to the status quo and whose legitimate feelings of abandonment have been cleverly exploited by parties espousing a variety of nationalist and anti-immigrant ideologies.