US President Donald Trump’s new tariffs seem haphazard but to me the reaction of people—including that of post-Keynesians—seems more interesting. The general reactions seem to be that the United States does not need to do anything. Across the political spectrum, people seem to peddle do-nothingism.

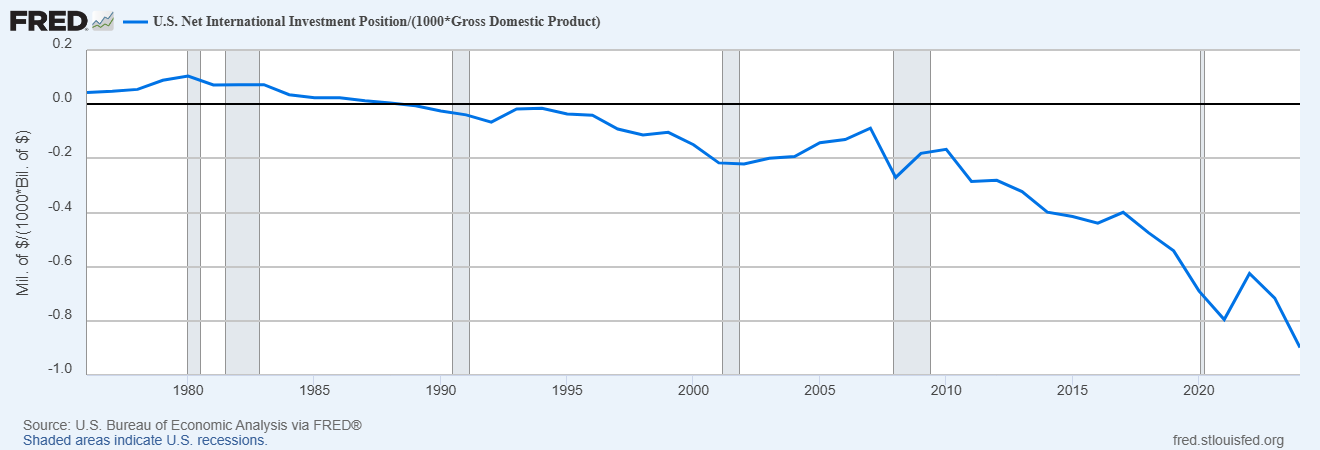

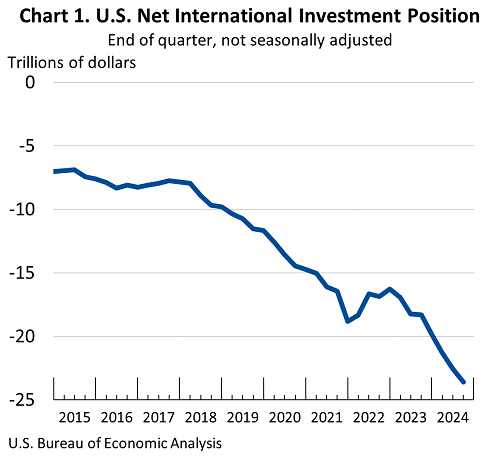

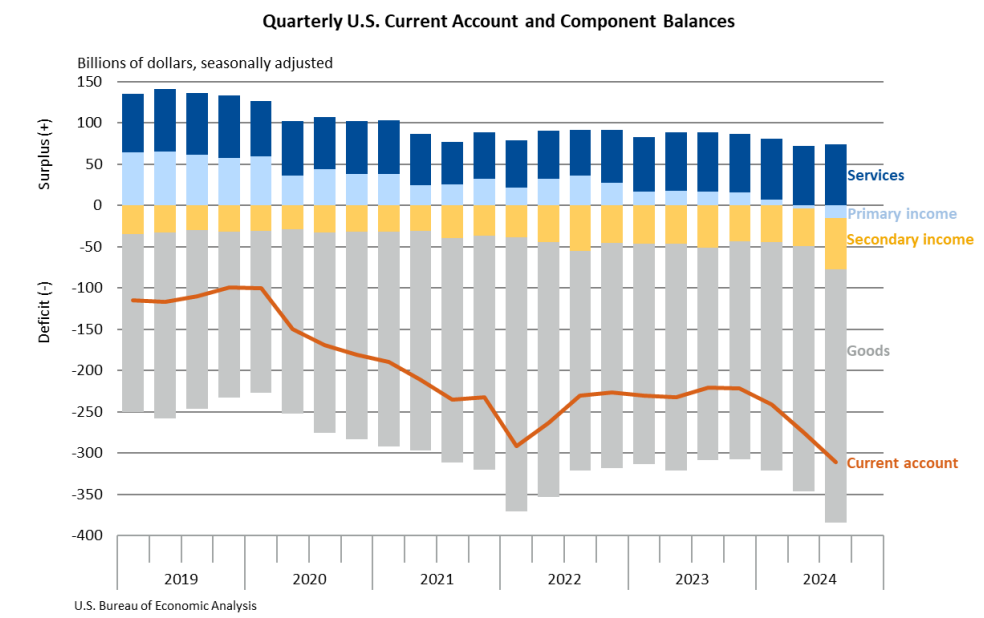

The United States’ balance of payments and international investment position is on an unsustainable path.

−1.0 means −100% of GDP.

Now that is just a chart but even from a theoretical perspective one can provide an analysis such as using Wynne Godley’s models.

Since the market mechanism does not reverse the process, an official intervention is needed.

Wynne Godley worried a lot about this and had proposed non-selective protectionism for the United States.

But going by people’s reactions with even the most radical sounding people sounding like fans of free trade, it seems to me that people simply would have rejected any proposal even if it were not haphazard.

Wynne Godley’s biographer Alan Shipman says this about him in his biography:

Of all Godley’s policy prescriptions, direct import controls were the one most roundly rejected by other economists, and least likely to be adopted by politicians with any chance of gaining power. The accusation of advocating a policy that was economically illogical, politically infeasible and inadmissible in international law hurt deeply, but never crushed his belief that import quotas should be seriously considered as an additional macroeconomic instrument. The depth of the wound emerged in an unusually personal statement to a 1978 conference on ‘Slow Growth in Britain’, convened by Oxford University’s Wilfred Beckerman in Bath. ‘I am disconcerted and distressed to find myself, together with the group of people with whom I work in Cambridge, in such an isolated position. For we seem to be the only group of professional economists who entertain the possibility that control of international trade may be the only way of recovering and maintaining the prosperity of this country; that free trade may be an enemy for the relatively weak’ (Godley 1979: 226).

…

References

…

Godley, W. (1979). Britain’s chronic recession—Can anything be done? In W. Beckerman (Ed.), Slow Growth in Britain. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

…

Talking of Wynne Godley, I found this nice autograph in his own book ‘Monetary Economics’, presumably to Lance Taylor?

Anyway, there are is one thing I wanted to address which is often made … that the trade deficit is just a reflection of the saving and investment decision of the private sector (or the country as a whole including the government) because there is an accounting identity connecting the two:

S − I = DEF + CAB

Where, S, I, DEF and CAB are private saving, private investment, government deficit and current account balance respectively.

But this accounting identity is not causation itself. Exports and imports depend on income and price elasticities, and income and price at home and abroad, so while private sector parameters of saving and investment can affect the trade balance, it is also affected by the elasticities. And if elasticities for imports are high relative to imports of the rest of the world, then that is a problem of competitiveness which the US is facing.