With Donald Trump threatening to impose tariffs and even retaliate on threats of retaliation, talks of protectionism is everywhere. It’s ironical that it took Trump to do this.

The usual criticism of selective tariffs is that they featherbed some industries. This was the motivation for Wynne Godley’s proposals for non-selective protectionism. With the claim that free trade is the best for everyone, also comes the implicit claim that there’s a market mechanism to resolve imbalances. Wynne didn’t believe there’s any such mechanism.

Here in this post, I will quote from all of his Strategic Analysis reports written for the Levy Institute in the years 1995-2005 which discuss this.

From, A Critical Imbalance In U.S. Trade:The U.S. Balance Of Payments, International Indebtedness, And Economic Policy, September 1995:

In-view of the potential seriousness of the problem, it is not too early to explore the possibility of using temporary, nonselective import restrictions at some stage, in accordance with the relevant provisions of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) as adopted and modified by the new World Trade Organization (WTO) as another means to achieve the required switch. Any such policy is to be sharply distinguished from illegal, protectionist measures used selectively to protect sectoral interests at home or against particular countries abroad.

…

Contrary to much popular supposition, the articles of the GATT, which have been adopted with some modification by the new WTO, sponsor the use of import controls if there is a conflict between the objectives of full employment and balance of payments equilibrium. Article 12 states in its first paragraph that contracting parties “in order to safeguard [their] external financial position and . . . balance of payments, may restrict the quantity or value of merchandise permitted to be imported.” Later, paragraph 3(d) makes it clear that import controls may be justified if “the achievement and maintenance of full . . . employment [generates] a high level of demand for imports involving a threat to its monetary reserves.” It seems that for the GATT, as for the WTO, the principles of nonselectivity and nondiscrimination are as fundamental as that of free trade as such. In particular, the use of nonselective controls for balance of payments reasons, as envisaged by Article 12, is a totally different kettle of fish from the discriminatory imposition of prohibitive tariffs on imports (for example, on goods imported to the United States from Japan) in support of sectoral interests. Such tariffs have recently been under active consideration by the U.S. government, in flagrant violation of the spirit and letter of the WTO agreements to which it is a signatory. Article 12 has recently received a new gloss in the understanding reached in 1994 as part of the Uruguay Round. Whereas the original Article 12 sponsors the use of quantitative controls (such as quotas) that lead to endless administrative hanky-panky, the new understanding expresses a welcome preference for “price-based” measures, by which it means “import surcharges, import deposit requirements or other equivalent trade measures with an impact on the price of imported goods.”

Obiter Dicta

If price-based import controls of the kind sponsored by the WTO (say, a uniform, nondiscriminatory tariff on all imports of goods and services) were used to reduce the US. propensity to import, it might be possible, indeed it might be necessary, to cut general taxes (or increase public expenditures) for as long as the tariff was in force. The scale of any tax reduction would depend on the extent to which the tariff was absorbed by foreign suppliers and on the United States’s price elasticity of demand for imports.

But what about free trade and its benefits? What about inefficiency caused by the featherbedding of domestic industries that are being kept on their toes by foreign competition? And wouldn’t the restriction of imports be neutralized by retaliation on the part of other countries?

The criticisms regarding featherbedding and inefficiency apply with full force to the kind of protectionist measures that the United States has been threatening to impose on Japanese cars and components. It cannot be too strongly emphasized that totally nonselective, price-based measures taken because of a strategic conflict between the need for balance of payments equilibrium and the achievement of full employment have an entirely different character from selective measures taken to protect sectoral interests. Nonselective “macroprotection” (it might as well be called) does not reduce imports below where they would otherwise have to be in the long run, so it does no harm to the United States’s trading partners; the important difference is that imports are brought to an acceptable level at higher levels of domestic output than would otherwise be the case.

As for retaliation, the measures considered here are only those nonselective measures that are in accordance with the provisions of the articles of the WTO and GATT. If, as a consequence, retaliatory measures were taken selectively against the United States, it would be the countries taking such measures that would be acting illegally and the United States could validly complain.

From, Seven Unsustainable Processes, January 1999 :

Policy Considerations

The main conclusion of this paper is that if, as seems likely, the United States enters an era of stagnation in the first decade of the new millennium, it will become necessary both to relax the fiscal stance and to increase exports relative to imports. According to the models deployed, there is no great technical difficulty about carrying out such a program except that it will be difficult to get the timing right. For instance, it would be quite wrong to relax fiscal policy immediately, just as the credit boom reaches its peak. As stated in the introduction, this paper does not argue in favor of fiscal fine-tuning; its central contention is rather that the whole stance of fiscal policy is wrong in that it is much too restrictive to be consistent with full employment in the long run. A more formidable obstacle to the implementation of a wholesale relaxation of fiscal policy at any stage resides in the fact that this would run slap contrary to the powerfully entrenched, political culture of the present time.

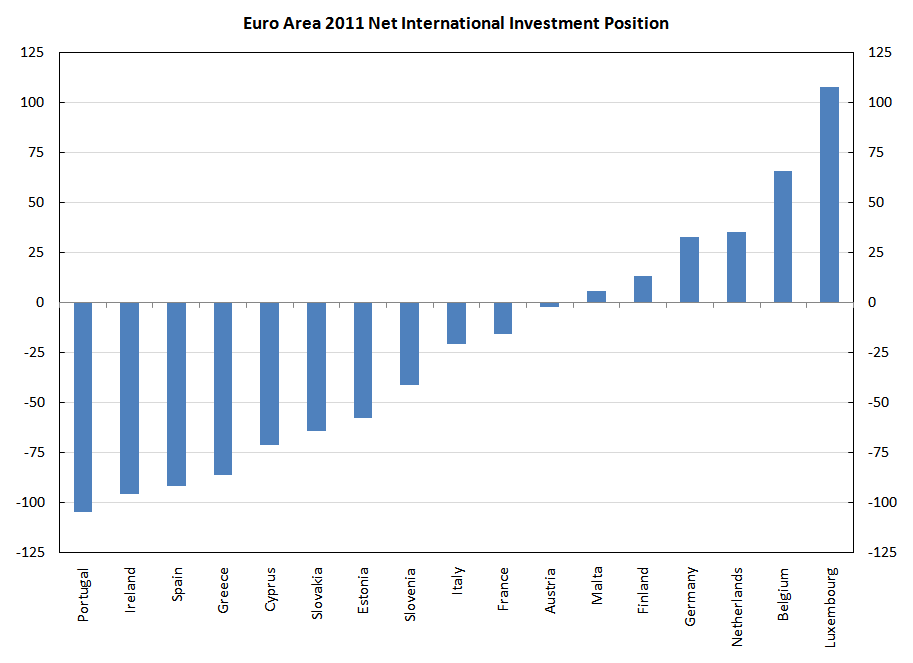

The logic of this analysis is that, over the coming five to ten years, it will be necessary not only to bring about a substantial relaxation in the fiscal stance but also to ensure, by one means or another, that there is a structural improvement in the United States’s balance of payments. It is not legitimate to assume that the external deficit will at some stage automatically correct itself; too many countries in the past have found themselves trapped by exploding overseas indebtedness that had eventually to be corrected by force majeure for this to be tenable.

There are, in principle, four ways in which the net export demand can be increased: (1) by depreciating the currency, (2) by deflating the economy to the point at which imports are reduced to the level of exports, (3) by getting other countries to expand their economies by fiscal or other means, and (4) by adopting “Article 12 control” of imports, so called after Article 12 of the GATT (General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade), which was creatively adjusted when the World Trade Organization came into existence specifically to allow nondiscriminatory import controls to protect a country’s foreign exchange reserves. This list of remedies for the external deficit does not include protection as commonly understood, namely, the selective use of tariffs or other discriminatory measures to assist particular industries and firms that are suffering from relative decline. This kind of protectionism is not included because, apart from other fundamental objections, it would not do the trick. Of the four alternatives, we rule out the second–progressive deflation and resulting high unemployment–on moral grounds. Serious difficulties attend the adoption of any of the remaining three remedies, but none of them can be ruled out categorically.

From, Interim Report: Notes On The U.S. Trade And Balance Of Payments Deficits, January 2000:

- Policy responses in principle come down to:

- Reducing domestic demand

- Raising foreign demand

- Reducing imports and increasing exports relative to GDP, preferably by changing relative prices.

- The danger is that resort (perhaps by default) will be had to remedy (a), in other words, that chronic and growing imbalances between the United States and the rest of the world come to impart a deflationary bias to the entire system, with harmful implications for activity and unemployment. Remedy (b) reads hollow when neither appropriate institutions nor agreed upon principles exist, but should not be dismissed out of hand. As for remedy (c), currency depreciation is the classic remedy. But, in view of the way global capital markets work, depreciation has ceased to be a policy instrument in any ordinary sense, and “floating” cannot be counted on to do the trick. Policymakers should be aware of the possibility of using nonselective (nondiscriminatory) control of imports in extremis in accordance with the principles set out in Article 12 of the WTO. Such a policy is to be sharply distinguished from “protectionism” as commonly understood.

…

Policymakers should not forget that under Article 12 the WTO sponsors the use of nondiscriminatory import controls if there is a conflict between the objectives of full employment and balance of payments equilibrium. Article 12 insists that the methods used to control imports should be nondiscriminatory with regard both to the countries and to the products affected and is therefore to be sharply distinguished from “protectionism,” which I understand to mean the use of selective controls to protect individually suffering enterprises. The provisions of Article 12 after revision as part of the Uruguay Round in 1994 expressed a preference for “price based” measures such as “import surcharges, import deposit requirements or other equivalent trade measures with an impact on the price of imported goods.”

Notwithstanding the deplorable advertisement, and the awful danger that the principle of nondiscrimination might be breached by powerful special interests, nondiscriminatory control of imports must stand as a realistic policy in extremis. The great advantage of import controls, as Keynes once said, is that they do stop imports from coming into the country.

From, As The Implosion Begins … ? Prospects And Policies For The U.S. Economy: A Strategic View, July 2001:

A substantial expansion of net export demand is easier spoken of than achieved. The classic remedy would be to bring about a dollar devaluation. However, by our reckoning, the size of the devaluation required — under the strong assumptions that world demand is unaffected and that the gesture is not neutralized by higher inflation — is very large, in the region of 20-25 percent. Unfortunately, there is no presumption whatever that market forces will automatically bring about the required adjustment in a timely way. In today’s world of free international capital movements, devaluation of the currency has ceased to be a policy instrument in any normal or direct sense.

Another possibility is that other countries, which have so far depended on the United States through her growing external deficit to provide a locomotive force for their own economies, should be encouraged to engage in some form of coordinated reflation. Unfortunately, there exist neither the institutions nor the agreed-upon principles needed to bring such a thing about. In the very last resort, the United States should not forget that nondiscriminatory measures to control imports (not to be confused with “protectionism”) are permitted under Article 12 of the successor to the GATT.

From The United States And Her Creditors, Can The Symbiosis Last?, Sep 2005:

- Protection directed selectively against countries with large trade surpluses against the United States—China, in particular—would not solve the problem and would be a very retrograde step in terms of global trading arrangements. If there must be protection (which we are not recommending), the U.S. government might prefer to follow the principles laid down in the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) Article 12.

- A resolution of the strategic problems now facing the U.S. and world economies can probably be achieved only via an international agreement that would change the international pattern of aggregate demand, combined with a change in relative prices. Together, these measures would ensure that trade is generally balanced at full employment. But there is no immediate pressure to bring such a change about because of the “symbiosis” to which our title refers. The short-term advantage of the present situation to the United States is that she is consuming 6 percent more goods and services than she produces, with high employment, low interest rates, and low inflation. The advantage to Japan and Europe is that their exports to the United States have helped fuel their mild aggregate demand growth, while China and other East Asian countries are building a mighty industrial machine by exporting growing quantities of manufactures and simultaneously accumulating a huge stock of liquid assets. This syndrome brings the word “mercantilism”2 to mind, with U.S. securities acting as the modern equivalent of gold. Those hoping for a market solution may be chasing a mirage.

…

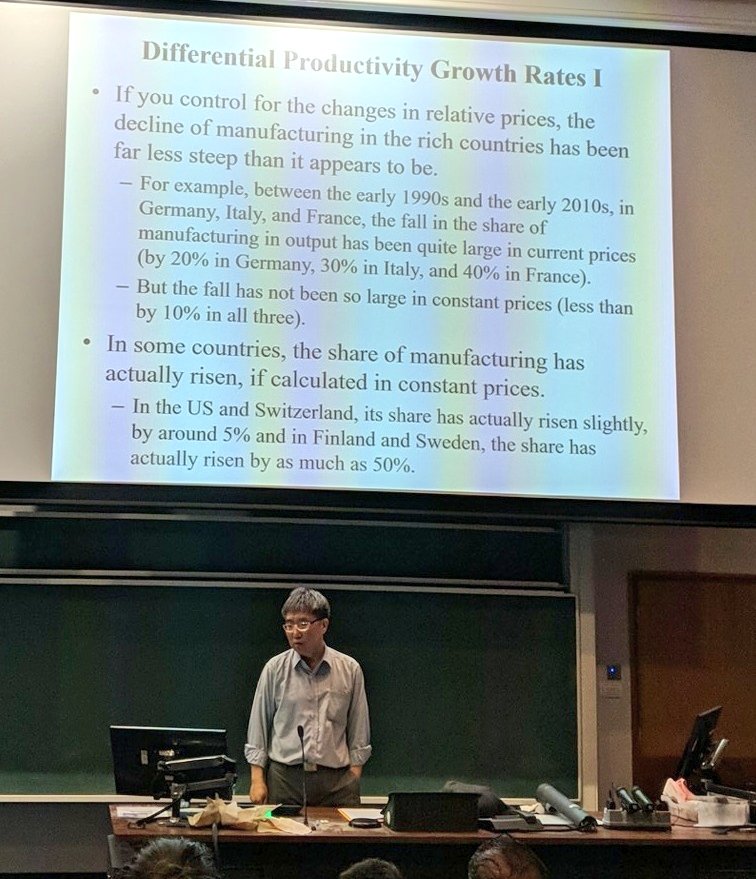

… increasing penetration of U.S. markets by foreign exports is having a devastating effect on what remains of the U.S. manufacturing industry, and this damage has already given rise to a great deal of protectionist pressure. But imposing a heavy tariff or quota restrictions selectively (e.g., on textiles imported from China), apart from the deplorable effect it would have on global trading arrangements, would hardly be effective as a way of rebalancing the U.S. and world economies as a whole.

Nonselective Protection

If pressure for selective protection threatens to become irresistible, the U.S. government might consider a less damaging alternative. It is not always remembered that the articles of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT 1947), which were adopted with some important modifications by the WTO, sponsor the use of import controls if there is a conflict between the objectives of full employment and current account equilibrium. Article 12 states in its first paragraph that contracting parties “in order to safeguard their external position and . . . balance of payments, may restrict the quantity or value of imports permitted to be imported.” The original Article 12 specified that any import controls should take the form of quantitative restrictions,12 but the new WTO version expresses a welcome preference for “price-based” measures, by which it means “import surcharges, import deposit requirements, and other equivalent trade measures with an impact on the price of imported goods.” In view of the potentially serious and intractable strategic predicament that looms in the medium term, it is appropriate that the possibility of introducing nonselective, price-based import restrictions—call them “Article 12 Restrictions” or “A12Rs” for short—should be calmly considered without fear that we or anyone else will be accused of political incorrectness or treason to the economics profession.

A devaluation of the currency, the proper remedy for imbalances, is virtually equivalent, in its effect on the current account and in all other respects, to the imposition of a uniform tariff on all imports accompanied by a subsidy of equivalent value on all exports. The main difference resides in the fact that a tax/subsidy scheme does not imply any revaluation of overseas assets and the income they generate. It is, accordingly, difficult to see why the introduction of a uniform surcharge on all imports, which may be seen as half of a devaluation, should arouse such passionate opposition, so long as the surcharge is completely nondiscriminatory with regard both to product and to country of origin. The significant difference between devaluation and A12Rs is that the former tends to result in a deterioration in the terms of trade for the devaluing country while the latter tend to improve them—but this difference is not likely to be of great quantitative importance.

Ignore, for a moment, the extreme difficulty of ensuring total nondiscrimination and the extremely bad impression that would inevitably be created internationally by the use of A12Rs. First, unlike devaluation, which is only remotely possible as a policy option, the U.S. government can impose A12Rs almost at will.13 They could conceivably take the form of an auctioned quota scheme,14 which would use a market mechanism to ensure that the (ex-tax) value of imports is relatively quickly restricted to what can be paid for by exports. Under such a scheme, all imports would need to be licensed, with the number of licenses restricted—with respect to the value of imports permitted—to correspond with some (high) proportion of exports in a recent period. The price of licenses to importers would then be determined by supply and demand.

To satisfy ourselves that the use of nondiscriminatory tariffs could generate an improvement in the trade balance and to explore various other properties of such a venture, we introduced a tariff scenario into our formal model. Starting from our baseline projection, it was assumed that a uniform tariff would be imposed at the rate of 25 percent on all non-oil goods at the beginning of 2006, generating additional revenue of $370 billion for the government. The second assumption related to the rate of pass-through, which is the extent to which the cost of tariffs would be passed along to U.S. consumers. The rate of pass-through was assumed to be 50 percent, implying a rise of 12.5 percent, including taxes, in the price of imports and in consequence a 2–2.5 percent fall in their volume. These changes are relative to what otherwise would have happened. It was further assumed that retaliatory surcharges (at an average rate of 10 percent) would be imposed by foreigners on U.S. exports, with effects on U.S. export prices and volumes matching those assumed for imports.

2 According to www.britannica.com, the underlying principles of mercantilism are “1) the importance of possessing a large amount of the precious metals; 2) an exaltation a) of foreign trade over domestic, and b) of the industry which works up materials over that which provides them; 3) the value of a dense population as an element of domestic strength; and 4) the employment of state action in furthering artificially the attainment of the ends proposed.”

…

12 This was drafted by James Meade, who informed one of the authors that against his very strong personal opinion he had been compelled by the U.S. delegation to specify quantitative controls. He would have been pleased by the new version adopted in 1994 as part of the Uruguay Round.

13 It is not suggested that the United States actually invoke Article 12, just that it follow Article 12 principles.

14 Such a scheme has already been suggested by Warren Buffett (2003).