Frequently, economists start discussing helicopters. This is the most counter-productive discussion. There are two things due to which they invoke this:

- Confusion

- Intent

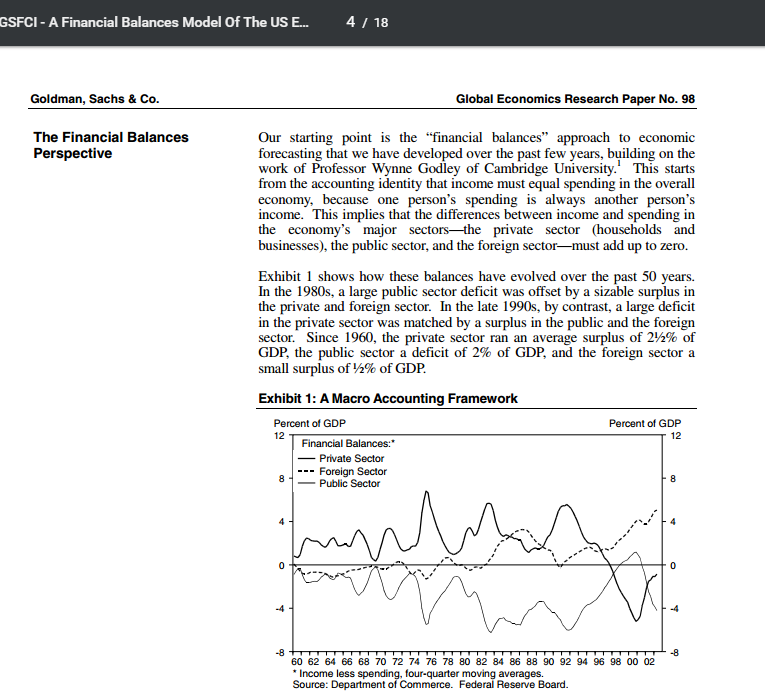

The confusion part is basically due to economists’ complete failure to understand what money is and how to account for it and this is due to a lack of training in national accounting/flow of funds etc.

The intent part is equally important. This is because economists are trained in thinking of fiscal policy as impotent. After the crisis, they have party understood the role of fiscal policy but the notion that fiscal policy is impotent is so deeply ingrained that it’s difficult for them to come out of it. This reason is not so obvious but can be proved as follows: If they really think that fiscal policy is not impotent, they should rather suggest a rise in government expenditure than some helicopters.

There’s a third reason.

Wynne Godley in his paper Money, Finance And National Income Determination, June 1996 had a good description of all this:

Modern textbooks on macroeconomics treat money in a remarkably uniform – and remarkably silly – way. In the primary exposition the stock of “money” is treated as exogenous in the two senses a) that it is determined outside the model and b) that it has no accounting relationship with any other variable. The reader is then invited to assume, pro tem, that the central bank controls “the money supply” so that it is constant through time. When the operations of banks are described, typically some thirty chapters later, the quantity of money is some multiple of commercial banks’ reserves as a consequence of these institutions having become “loaned up”.

Silly? The money stock, as revealed in real life financial statistics, is as volatile as Tinkerbell – for good reasons, as I shall argue below. How can it be sensible to undertake a thought experiment in which the flickering quantity called “money” is literally constant through periods at least long enough for capital equipment to be planned, built and commissioned – and for lots of other things to happen as well? And the other, “money multiplier”, story has the strange defect that, while giving some account of how credit money might be created, it completely ignores the impact on spending of the counterpart changes in bank loans which are assumed to be taking place; perhaps it is because loan expenditure would mess up the solution of the IS-LM model when alternative assumptions about “the money supply” are used, that the supposed process of money creation normally gets separated from that of income determination by so many chapters.

The bibles of the neo-classical synthesis don’t help. There is a spectacular lacuna in the constructions presented, for instance, by Patinkin, Samuelson and Modigliani with regard to the asset side of commercial banks’ balance sheets. Usually the role and

even existence of bank credit is simply ignored. Modigliani (1963) gives banks (with regard to their assets) no role other than to hold government bonds; and Milton Friedman famously used a helicopter when he wanted to get more money into the system.There is a reason for all this. It is that mainstream macroeconomics postulates in its basic model that macroeconomic outcomes are all determined by relative prices established in Walrasian markets. Individual agents are held to engage in a market process of which the outcome is to find prices for product, labour and money which clear all three markets plus, by Walras’s law, the market for “bonds”. But as is now well known, there is no use for money in the Walrasian world even though, paradoxically, “money” is a logical necessity if the model is to be solved.

[boldening: mine]

There is no need for helicopters. All is needed is a description via social accounting (i.e. national accounting). Just say “increase government expenditure” to the government or “expand fiscal policy”.